On 18 December 2021, professional men’s badminton in India witnessed one of its highest points when Kidambi Srikanth edged out Lakshya Sen in the semi-finals of the BWF World Badminton Championships (hosted in Huelva, Spain) in an epic three-set encounter.

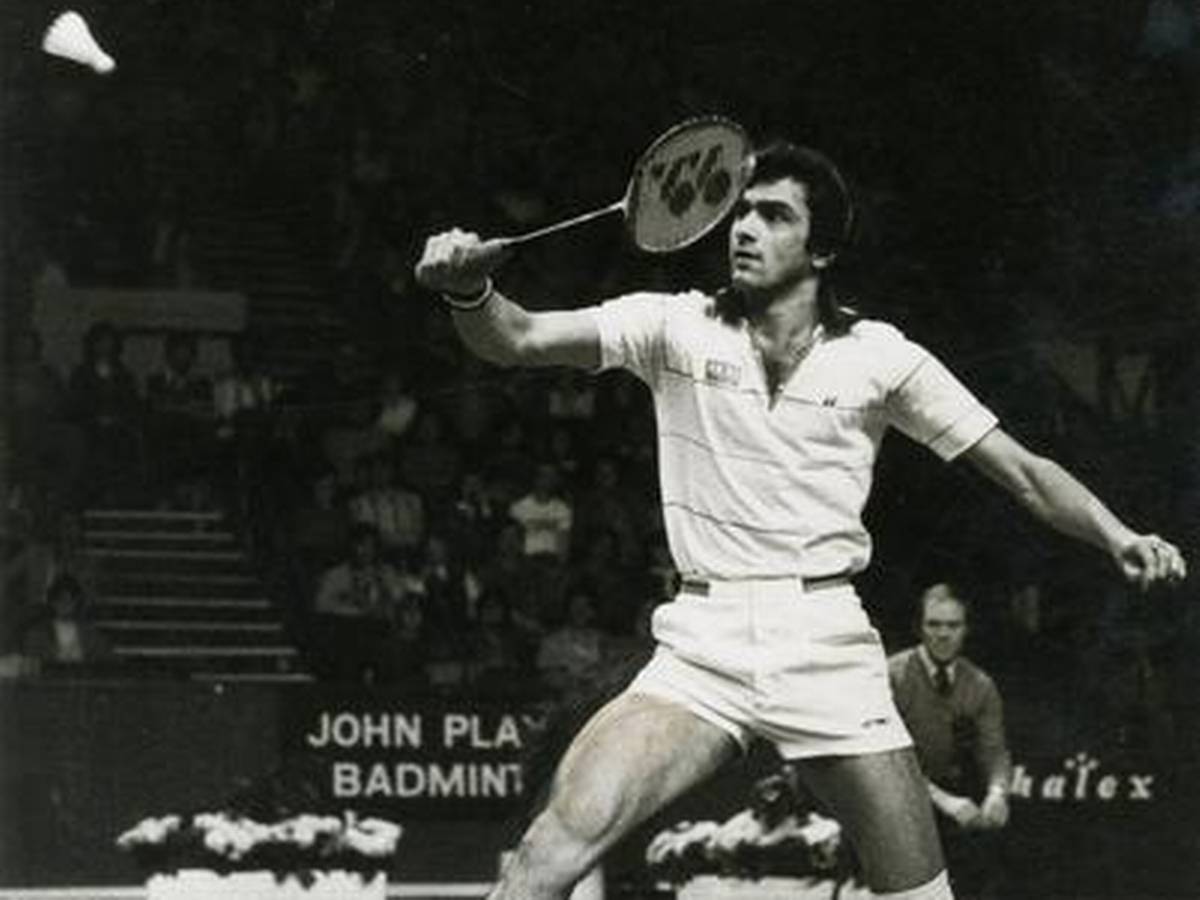

(Image above of Prakash Nath on the left and Devinder Mohan on the right courtesy National Badminton Association)

Lasting over one hour and nine minutes, Srikanth overcame Sen 17-21 21-14 21-17 to become the first Indian man to reach the finals of the BWF World Championships. While Sen finished with a bronze medal, Srikanth lost to Malaysia’s Loh Kean Yew in the final and bagged a silver.

There is little doubt that fatigue played a role in Srikanth’s eventual loss to the champion following his exertions in the semi-finals. Given the road ahead, should the talented Indian shuttlers have decided not to play against each other and delivered an outcome via a coin toss?

Given the ultra-competitive nature and the economics of the game today, it seems highly unlikely that Sen and Srikanth would have ventured to take this route, But in the 1947 edition of the All-England Championships—which was considered the world’s premier badminton tournament before the official world championships were launched in 1977—two talented Indian shuttlers and friends decided to determine their quarter-final tie via a coin toss.

Prakash Nath, a virtuoso stroke maker, and Devinder Mohan, a power hitter, met under these circumstances at the All-England Championships, the first to be played since the conclusion of World War II. Without any records to indicate a current form of each player entering the tournament, seedings were allotted based on performances before World War II.

India had fielded its two best players — Nath and Mohan, who were fellow national champions, fierce professional rivals and good friends. In fact, across five national championships between 1942 and 1946, no one won the singles title except for Nath or Mohan.

So, the Indian Badminton Federation selected both of them for the tournament in London organised at the Harringay Arena to compete against the best in the world. Given the arbitrary seeding system and the general lack of awareness about how good the two of them were, the All-England authorities put them together in the same quarter of the draw.

When Nath and Mohan arrived in London following a long journey from Lahore to London, they expected to face each other in the final for the title. But to their shock, they realised that the draw wouldn’t allow for it, and only one had the chance to reach the final. Despite their strong protests against the tournament committee, chief referee Herbert Scheele refused to consider their complaint and asked them to get on with it.

Both Indian shuttlers had no real trouble reaching the quarter-finals, although Nath did overcome the challenge of popular defending champion Tage Madsen of Denmark across three sets in the first round in front of a then-record crowd of 25,000 at the Harringay Arena.

When it was time to face each other, they decided to take a rather novel step. The shuttlers knew each other’s game so intimately, foresaw a long and gruelling encounter, and realised that whoever came up on top would be too fatigued and stiff to compete in the semifinals. So, instead of playing an intense match, both men decided to flip a coin instead.

Speaking to veteran badminton writer Dev Sukumar in a 2007 interview, Nath recalled, “It made no sense to tire each other out. We knew each other’s game inside out. We aimed to win the trophy. Devinder bore no ill-feeling towards me after I won the toss and played the semifinal. We were friends throughout our lives.” The British press went wild with the story stating how a valuable gold coin was used for the toss between the two, although Nath denied this rumour.

Nath won the coin toss, received a warm embrace from his friend and proceeded to the semifinals where he beat an Englishman called Redford before coming up against Denmark’s Conny Jespen in the final. Nath was confident of defeating the Dane, but everything changed when he read The Times newspaper on the morning of 3 March.

Giving Up the Racket

Partition was in full swing, and his hometown of Lahore was in flames. He had read about how the city was engulfed in violent riots. More specifically, the entire area around his house had been set on fire. With all lines of communication down, he didn’t know whether his family was alive or not. Although Nath was in no state of mind to play the final, he did.

In another interview, he recalled how the day of the final felt like a ‘bad dream’ and that he just ‘went through the motions’. What should have been a day of celebration ended up becoming just the start of a long and drawn-out nightmare.

When Nath got back to Lahore, it wasn’t a town he didn’t recognise anymore. With his home ransacked, a thriving family business destroyed and bloodthirsty mobs running wild on the street murdering people, it was now a question of survival. Nath almost lost his life on several occasions, and those days haunted him for years thereafter.

Given the religious polarisation of the times, Nath and surviving members of his family had no choice but to leave everything behind, and migrate to a refugee camp in Delhi. Badminton was the furthest thing from his mind, and he vowed to never touch a racket until his family got back on their feet. And he didn’t waver from his vow.

The family eventually settled in the national capital, where he built a thriving electronic machine tools business. Living a recluse life, he eventually passed over the family business to his son in 2005, went into retirement and passed away in relative anonymity in 2009. His friend, Mohan, meanwhile, won a couple of more singles titles in the 1949 and 1950 national championships, besides leading the Indian contingent in the Thomas Cup (1948, 1952). Among other things, he led the Indian contingent in an upset win against the much-heralded Danes in 1952.

To this day, Mohan remains a legend of Indian badminton. Suffice it to say, one could speculate whether Nath could have become the first Indian to win the All England Open Badminton Championships before Prakash Padukone’s special run in 1980. Had drastic political and social circumstances of the day not forced him to give up the game, maybe he could have gone on to achieve greater things in badminton. Sadly, we’ll never know.

But at least he had that moment with his friend Mohan.

(Edited by Yoshita Rao)

No comments:

Post a Comment