In the suburban village of Okhla, one of the oldest in Delhi, stands a tall board that reads ‘Sarai Julena Gaon’. This signboard is the last remaining proof of a sarai, or rest house, built for weary travellers built in the 18th century. Today, the area houses DDA (Delhi Development Authority) flats.

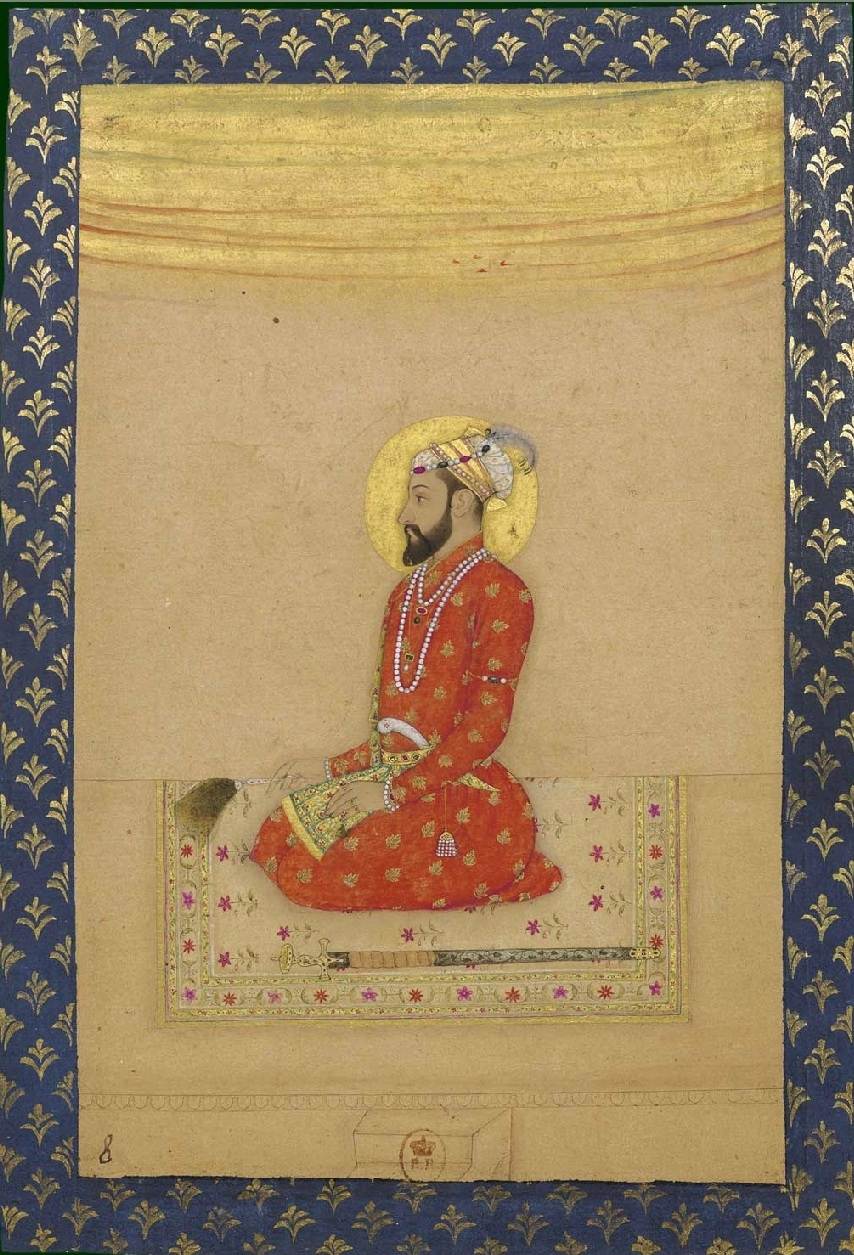

The architect of this lost structure was a woman who once held much importance in the Mughal courts, even though she was a Christian and the daughter of a maid in the palace. This is the story of Juliana Dias da Costa, a woman of Portuguese descent, who worked in the Mughal harem and became a close confidant of Bahadur Shah I, India’s eighth Mughal emperor.

Oracle of the emperor

As historian and writer Taymiya R Zaman details in her paper, the Portuguese colonial holdings (Estado da India) were weakening in 17th and 18th-century India, owing to the English, French and Dutch slowly gaining ground.

“The eighteenth century also saw the Mughal Empire…balanced precariously around the possibility of collapse, a consequence of the rise of successor states and political aspirations of European trading companies. In such a landscape, one Juliana Dias da Costa, a Portuguese woman who held enormous power and influence at the court of Mughal king Bahadur Shah I, attracted the mention of many,” Zaman said in Visions of Juliana: A Portuguese Woman At The Court Of Mughals.

There is simultaneously a lot, and very little, to say about Juliana and her life. Remembrances of her in the past have crossed barriers of language and even time, and in some cases, she has been reimagined from the eyes of the person writing about her. Regardless, all accounts converge on one thing — she was, in her lifetime, one of the most prominent figures in the Mughal courts.

Because Juliana’s life faded into obscurity once India attained independence and her descendants lost their land, existing accounts of her early life are conflicting. No clear dates of her date of birth and death exist, alongside details regarding just how she came to the courts.

However, historians opine that her parents were possibly prisoners captured during the Mughal raid in Hugli in 1632, which was ordered by Shah Jahan as a response to Portuguese attacks on Mughal ships. Another theory states that her parents fled to the Mughal court around 1663 from Cochin after the city was seized by the Dutch. And as per the final theory, she was the wife of a Portuguese surgeon who came to the courts of Shah Jahan’s son Aurangzeb, sent by Portuguese officials.

As per the first theory of how she came to the Mughal courts, Juliana and her mother were given to “a begum of the household”, whom they served until her death. After the begum died, the mother and daughter came under the care of one Padre Anton Magellan, who arranged Juliana’s marriage to an unnamed Portuguese man after her mother died. The man died in battle shortly after.

She was known to be eloquent and wise, with an immense knowledge of medicine from her very childhood. She was entrusted with the education of several royal children, which in turn made them privy to family secrets, businesses, and treasures. She also served as a doctor for the royal women, charge de affairs for the harem, and was a diplomat and ambassador for the Portuguese.

In their book Juliana Nama, Raghuraj Singh Chauhan and Madhukar Tewari wrote that Aurangzeb entrusted the education of Prince Muazzam (later Shah Alam), his second son, to Juliana. She was 17 and he was 18 at the time. Muazzam was “filled with remorse for the merciless imprisonment of his grandfather Shah Jahan”, and the “seeds of a lifelong affair were sown”.

It is said that Juliana had acclimatised the young prince to Christianity to such a point that he would kneel before Jesus in prayer, send blessings to the church, and just about everything short of baptism.

As has been documented extensively, the prince held much contempt against his father, who had him imprisoned at one point for suspected treason. A loyal Juliana stuck by Muazzam’s side to the point where she risked her own life to give him a comfortable life in prison for seven long years, smuggling in gifts and other items of luxury.

This loyalty would pay Juliana when the prince took over the throne and became Bahadur Shah I. Juliana remained by his side even in his battle for the throne, where she “prophesied [his] victory…against his brother because of the prayers of all the Christians were with him”, and “encouraged him to make one last stand while riding beside him on an elephant”. Author Francois Valentyn referred to her as the “oracle of the emperor”.

“Her level was such that when she would ride, she would be accompanied by five or six thousand men on foot. Other people, no matter what their level, would seek her counsel and favour, and if she intercedes on their behalf, their wishes would be granted,” wrote Zaman, “But this kind bibi, in whose soul chastity and modesty were embedded, despite this wealth, honour and high position, would spend all her time in humility and piety.”

‘A lost Indian past’

Juliana’s position in the Mughal court was viewed as a vital voice of the fading Portuguese empire, Zaman wrote, “Jesuit missions to India had a long history…[but] The success of these missions was debatable as Mughal willingness to engage with Jesuit ideas was not indicative of imminent conversation…In his account of Juliana, [Ippolito] Desideri is flirting with this possibility by pointing [her] position in the Mughal household as the custodian of family secrets and the teacher of royal children, and as exercising an influence on the king that benefitted Jesuit missions and Christians in general.”

Author Jean-Baptiste-Joseph Gentil stated that after the battle where Juliana prophesied Bahadur Shah’s win, she was given wealth and the palace of Dara Shikoh. Authors of Juliana Nama said that her interventions in the rulings of the Mughal court helped her attain several feats for the Portuguese. Surat was declared a duty-free port for the Portuguese, and a church was built thanks to her donations. For her work for both sides, she was also given a few villages around Delhi.

Juliana’s loyalty to the Mughal kingdom would remain even after Bahadur Shah died in 1712, and went on to serve his successors and sons. She built the sarai under the reign of Muhammad Shah ‘Rangeela’, but all that remains of it today is the Sarai Julena area, and a village named Julena. Juliana died sometime during ‘Rangeela’s’ reign.

Her descendants eventually lost their land as the British came in, and after India became a free nation in 1947, her mentions in scholarly and historic works more or less vanished. So where should she find the rightful mention? In Portuguese archives, or the history of Mughal India? For now, both seem to give varying, incomplete and obscure accounts of her life.

As per Indian author Bilkees Latif, Juliana is “emblematic of a lost Indian past, in which people could claim multiple religious and ethnic allegiances”. Zaman said, “Affected by religious violence in India, and by the admiration for Juliana….[Bilkees] imagines Juliana as representing better times”.

References: Taymiya Zaman, The Times of India, Indian Express, Juliana Nama

No comments:

Post a Comment