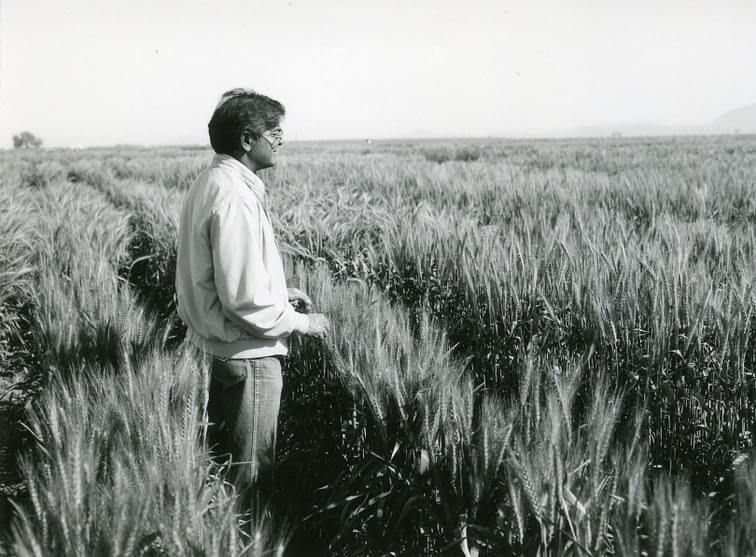

Dr Sanjaya Rajaram, who passed away on 17 February 2021 at his home in Ciudad Obregón, a city in the Sonora province of Mexico, ranks among the most outstanding agricultural scientists of our time. Building on the success of the Green Revolution, his research is responsible for the development of 480 varieties of wheat that small and large farmers grow across 51 countries over 6 continents, leading to an increase in global production by more than 200 million tonnes.

Celebrating his incredible achievement, the Indian government posthumously awarded him the Padma Bhushan, the third-highest civilian honour, earlier this month.

Back in 2001, the Government of India had awarded him the Padma Shri.

According to the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), his varieties of wheat are grown on some 58 million hectares worldwide and have prevented starvation in different parts of the world.

Rajaram was just 29 when he took over CIMMYT’s wheat breeding program after Nobel Laureate Dr Norman Borlaug in 1972. He served the organisation for 33 years, including seven as Director of the Global Wheat Program, before joining the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA). He would formally retire from his official duties in 2008.

What stands out about the 480 varieties of wheat he developed is their “increased yield potential and stability, along with wide adaptation and resistance to important diseases and stresses”.

“These varieties include the spring and winter wheat cross Veery, which was released in 36 countries; new approaches to disease resistance, for instance, ‘slow-rusting’ wheat varieties; and largely reduced foliar blight susceptibility in semi-dwarf wheat…One of his wheats, PBW 343, is India’s most popular wheat variety. His varieties have increased the yield potential of wheat by 20 to 25 per cent,” according to this tribute by CIMMYT.

Rajaram also won the World Food Prize in 2014 for the “crossing of winter and spring wheat varieties, which were distinct gene pools that had been isolated from one another for hundreds of years”. This, the jury argued, “led to his development of plants that have higher yields and dependability under a wide range of environments around the world”.

Making a Mark in Agriculture

Born in 1943, Rajaram grew up in a modest household near a small farming village of Raipur in Varanasi district, Uttar Pradesh. His family made a living off their 5-hectare farm growing wheat, maize and rice. Rajaram, meanwhile, went to a village school about 5 km from his home, where he completed his primary and secondary school education. A bright student, he won a scholarship to attend high school, following which he went to the University of Gorakhpur where he obtained a BSc in agriculture. Following graduation, he obtained his master’s degree from the Indian Agricultural Research Institute in New Delhi, where he studied genetics and plant breeding under Dr MS Swaminathan, renowned for his leading role in India’s Green Revolution.

Following his master’s degree, he went to Australia to complete his PhD in plant breeding at the University of Sydney on a scholarship. There he met with Dr IA Watson, who had studied alongside Dr Norman Barlaug as a graduate student at the University of Minnesota. It was Dr Watson, who would recommend Rajaram to Barlau at the CIMMYT in Mexico. This introduction would play a pivotal role in what would become a distinguished scientific career. Given his family background in farming, Rajaram knew his future lay in agricultural science where he could make a significant difference in food production and institute long term positive change.

Innovator Extraordinaire

Rajaram began his tenure at CIMMYT in 1969 working alongside Borlaug in experimental fields of Ciudad Obregón, Toluca and El Batán in Mexico. With their base of operations in El Batán, southern central Mexico, CIMMYT is a “non-profit international agricultural research and training organisation focusing on two of the world’s most important cereal grains: maize and wheat, and related cropping systems and livelihoods,” notes their website.

Established in 1943 as a joint venture between the Rockefeller Foundation and the Mexican Ministry of Agriculture, it began as a pilot program to facilitate food security in Mexico and abroad “through selective plant breeding and crop improvement” with the initial objective of breeding rust-resistant (wheat leaf rust is a fungal disease) and higher-yielding wheat.

The programme was initially headed by Borlaug, who would not only go on to develop game-changing varieties of wheat but also far-reaching approaches to plant breeding.

His most significant contribution to the discourse around plant breeding was the development of high volume ‘shuttle breeding’. According to this paper published in 1989, “Shuttle breeding uses diverse ecological environments to develop improved varieties with higher adaptability.” Borlaug would also lead efforts at breeding improved varieties of wheat in India as well, and become the scientist who helped engineer the country’s Green Revolution as well. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1970 for his efforts in saving millions from starvation.

From 1969 to 1972, Rajaram would conduct his research and fieldwork under the supervision of Borlaug before succeeding him to lead the wheat breeding team at CIMMYT.

According to the World Food Prize citation, “Like Borlaug, Rajaram had the extraordinary ability to visually identify and select for crossbreeding the plant varieties possessing a range of desired characteristics, an ability that was essential to wheat breeding in the 1980s and ’90s.”

His new varieties of wheat would find their way in places where they were struggling for better yields like the remote corners of China, Pakistan and even Brazil where he developed an aluminium-tolerant variety that successfully grew on acidic soil. Going further, he could foresee some of the diseases that could threaten this staple crop. Working alongside his team at CIMMYT, they would enhance the resistance to these diseases in their varieties of wheat.

“Rajaram also developed wheat cultivars with durable resistance to rusts—the most damaging disease to wheat worldwide—through his concept of ‘slow rusting’. He used multiple genes with minor effects that slow down disease development, thereby minimizing the impact on yield without challenging the rust pathogen to mutate and overcome resistance. The varieties produced using this technique have been grown on millions of hectares worldwide. His method proved a cost-effective and environmentally sound way to control plant disease,” notes the citation he received after winning the World Food Prize in 2014.

Going beyond his innovation, Rajaram was also a man who emphasised the importance of sharing his knowledge and findings with the rest of the world. Training and mentoring over 700 scientists from the developing world, his knowledge and skill-set were passed onto others who would themselves go on to accelerate the development of high-yield varieties of wheat.

Despite taking up Mexican citizenship, Rajaram never lost track of India and remained active in promoting wheat breeding, genetic engineering and precision agriculture here. His legacy, however, extends to the work he did for the world, and that’s something we should celebrate.

(Edited by Yoshita Rao)

No comments:

Post a Comment