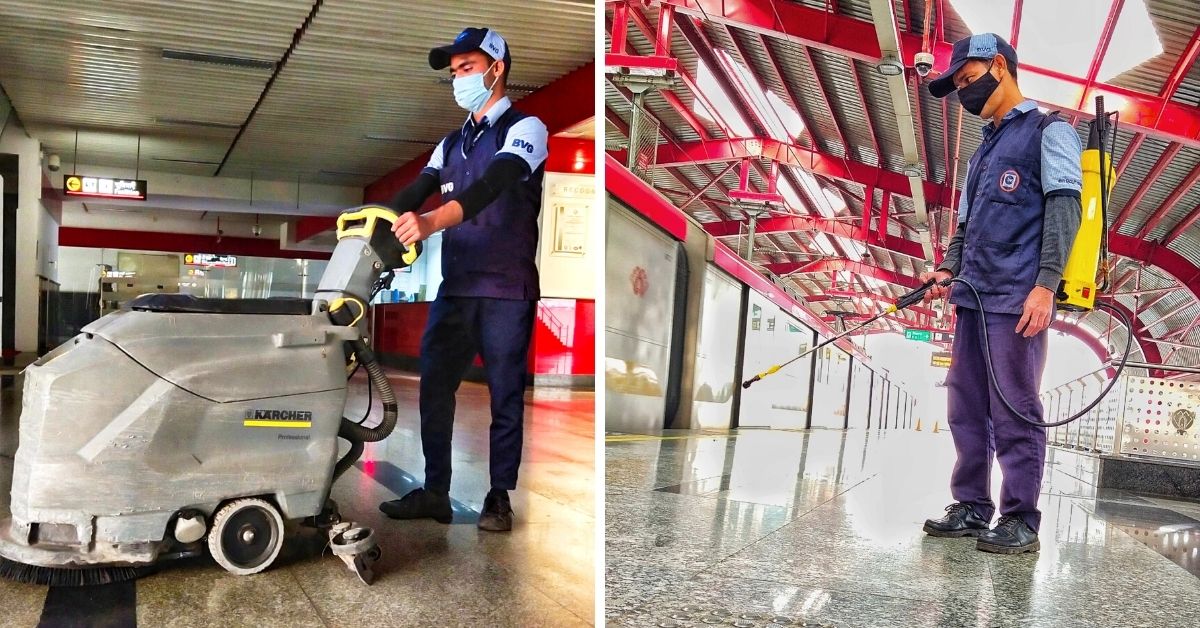

It’s very unlikely that you haven’t come across at least one employee dressed in BVG India Ltd’s telltale dark blue uniform.

The Bharat Vikas Group has its presence across 850 companies and areas, including airports, corporates, and ambulance services, alongside Parliament House, Rashtrapati Bhavan, and more. It works in housekeeping, facilities management, gardening, medical and agriculture sectors that benefit millions of lives every day.

But BVG is not just another company that caters to its clients to outsource services. On the other hand, it started, and continues with, a great cause – to generate employment across rural India.

Founded by Hanmantrao Gaikwad from Maharashtra, the company began at Tata Motors, then Telco, intending to employ eight youths from his native, Satara.

Changing fate

Hanmantrao joined Tata Motors in 1994 as an engineer. But in 1997, he quickly gained recognition within the company when he saved Rs 2 crore, by suggesting a way to reuse old cables for new cars with innovative modifications. The move saved the company from having to waste those cables, while being economical.

Hanmantrao leveraged his reputation when some people from his village approached him seeking a job with the company. “I requested the manager to employ them, and the company agreed to hire them on a contract basis. The management also agreed to lend me Rs 60 lakh from Tata Finance to purchase cleaning equipment,” he says.

With this, he established Bharat Vikas Pratishthan, a trust to employ the eight people. This laid the foundation of the Rs 2,000-crore empire.

But the idea to help rural folks find employment stemmed from Hanmantrao’s own childhood struggles.

A bright student born in Rahimatpur village of Satara, he pursued education through a government-funded scholarship of Rs 15 per month. Hanmantrao’s father, a low-rank clerk, had diabetes and a majority of his salary went into his treatment.

“There was no electricity at home till I was in Class 6, and my brother Dattatray and I would have to study under a chimney for light. Later, we moved to Pune, living in an 8×9 feet space in the Phugewadi area,” the 50-year-old says, adding that he took admission in Modern High School.

Hanmantrao recalls that when his father’s health deteriorated, his mother had to sell her jewellery to meet expenses. “I would help by selling mangoes for Rs 3 per dozen to make ends meet,” he says.

“My mother later took a job with the municipality school as a teacher to run the family, while my father was bedridden. I continued studying for a diploma in electronics at Government Polytechnic, Pune and lost my father to a heart attack during my second year,” he says.

After completing his diploma, Hanmantrao joined Phillips as a trainee, but soon quit. “I decided to pursue a degree in engineering from Vishwakarma Institute of Technology (VIT) instead. My mother loaned Rs 15,000 from Pune Municipal Co-operative to pay my tuition fees,” he says.

He adds, “To fund my academic expenses, I began taking coaching with a friend, and sold jams and sauces for a company, earning a monthly sum of Rs 5,000.”

He continued doing odd jobs to fund his education and eventually joined Tata Motors.

“I understand the struggle that a person from a rural area undergoes, as I, too, have experienced that ordeal and pain,” he notes. “I did not want rural youths to suffer the same fate as me, and wanted to create a platform to benefit them with employment,”

Hanmantrao quit his job in 2000 and formally converted the trust to establish Bharat Vikas Group (BVG) India Ltd. in 2001 to employ youths from rural India.

The same year, his company bagged a big contract with G E Power in Bengaluru. “We drove overnight and worked over the weekend to get the factory cleaned and ready by Monday. We managed to seek eight more contracts from the city in the next few months, and later received more work from Hyderabad and Chennai,” he says.

Hanmantrao says that his staff was well trained, polite and sincere, and the same qualities reflected in their work. “I provided training through local institutes and even chalked courses which included elements required in housekeeping and cleanliness. It had a formal structure and needed following certain guidelines to gain the required skills,” he says.

Since then, there has been no looking back. The company bagged a contract with Parliament House in 2003, followed by the Prime Minister’s office and the Rashtrapati Bhavan in 2005. “We initially got work to clean and maintain the library and annexe. The difference between these two entities and the rest of the premises in cleanliness became clearly visible,” he says.

He says that the members of Parliament were impressed with the work, and eventually handed over all the housekeeping and gardening work to the company.

“But we were a small company and ill-equipped to take the huge responsibility. The company’s turnover was about Rs 2 crore and required an immediate investment of Rs 40 lakh to bid and win the six-month contract,” he says.

Hanmantrao says he was confident that if his employees continued to deliver the standards raised by the company, the contract would be renewed. “Things worked as expected, and the company grew to Rs 16 crore in 2005 and over Rs 400 crore by 2010,” he says.

Today, with employees nearing 70,000, the company earns a turnover of Rs 2,000 crore with clients such as Mercedes Benz, Volkswagen and Accenture, as well as temples like Shirdi Sai Sansthan Trust, Somnath, Dwarka, 16 airports, and more.

Giving a life of dignity

From Facility Management Services (FMS) provider, BVG has entered the ambulance segment, which has benefited over 65 lakh people, Hanmantrao says. “The service is available in Maharashtra, Jammu Kashmir and Ladakh under the Public-Private Partnership model with the respective state governments. They are free, and the user has to dial 108 to access the emergency healthcare that promises to reach within 15 minutes in cities,” he adds.

The company also has its presence in waste management treatment and works in tandem with local bodies in Mumbai, Pune, Bengaluru and others, handling over 3,000 tons of waste each day.

“We also cater to farmers by introducing modern scientifically tested methods to improve agricultural yield and livestock health. Our products help to increase yield by 50 per cent,” he says.

Hanmantrao says he had to overcome the hurdles of fighting local resistance in their respective locations. “There is always some form of resistance from previous employees or contractors when we bag a contract. Convincing local companies is a challenge and also a part of the business,” he says.

The company is in the process of going public and will soon become a publicly owned enterprise. “We have already initiated the process with SEBI and should announce going public by January end,” the entrepreneur says.

Hanmantrao says he will continue his mission to employ rural India and help them live a life of dignity. “I want the name BVG to be associated with the life of every person in the country,” he says.

Edited by Divya Sethu

No comments:

Post a Comment