This article has been sponsored by Jaipur Rugs.

Kamli, a resident of Dhanota village in Rajasthan’s Shahpura tehsil, was in a deep predicament. It had been three years since her husband Tejpal had left her with their four children back home, and made his way to Punjab in search of a livelihood. But in all these years, he had neither sent any money, nor visited, nor even called his family. Where was he, and how was she to feed four additional mouths in his absence?

Unfortunately, Kamli’s story is not an isolated one. Rajasthan has one of the lowest unemployment rates for women, who find themselves victims of violence, neglect, archaic practices like the purdah system, child marriage, and more.

Moreover, caste plays a major role in further subjugating these women, who mostly belong to marginalised groups including Raigar and other communities. This was a reality that Nand Kishore Chaudhary, founder of Jaipur Rugs, was all too familiar with.

‘Who am I?’

“When I first began Jaipur Rugs, it invited the ire of several people, including my own family. All the weavers I wanted to work with were considered ‘untouchable’. I was not allowed to enter my house, those in my mohalla (colony) told me I was not allowed to live there, people would not shake my hand, all because I was working with achoot log (untouchable people). That’s when I realised what a big role caste plays in determining a person’s worth in society,” Chaudhary, born in a traditional Marwari family in Churu, tells The Better India.

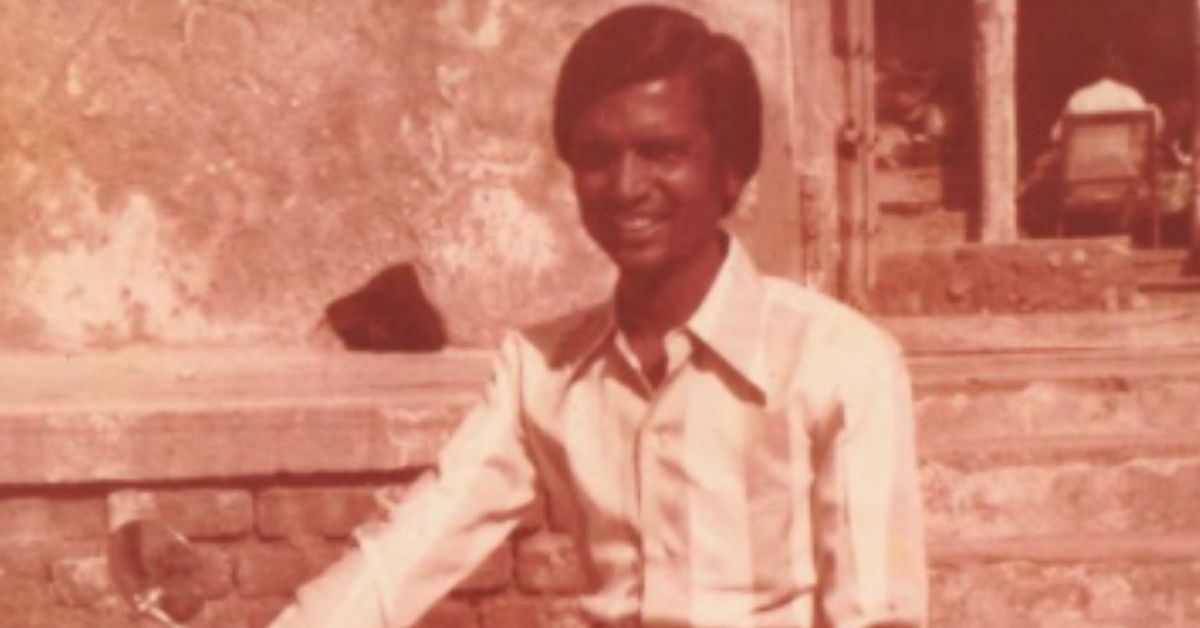

In 1978, Chaudhary (68) began Jaipur Rugs, now India’s largest manufacturer of hand-knotted rugs and carpets, with Rs 5,000 and a vision to make a difference. He borrowed the sum from his father, forgoing a job in his family’s traditional shoemaking business, as well as a lucrative government job in a national bank to realise this dream.

“I wrote a thank you letter to the bank for considering me for the opportunity,” he recalls. “Then I sat down to think — ‘Who am I? What is my passion? What are my natural abilities?’”

An introverted Chaudhary had grown up reading the works of Gandhi and Tagore, as well as spiritual texts, all of which had ingrained a deep consciousness of his heritage and values in him.

“I found that I wanted to do something that I would love while working for the benefit of the people. I also found that India had great demand for carpet export, and realised that this would give me the opportunity to travel to the remotest of villages to work with the people there. These are folks who are ‘rejected’ by society, and I wanted to highlight that their existence is integral and important,” he says.

Jaipur Rugs began with two looms and nine artisans in Churu, and Chaudhary himself underwent training with the weavers to learn the art. The carpets were exported under the name Bharat Carpet Enterprise. Just three years later, 10 additional looms were now part of the venture, which had established itself in Ratangad, Jodhpur, Laxmangarh and Sujanghad.

From here, Chaudhary went on to spend 13 years working with rural artisans in Gujarat alongside his brother. He stayed in their hamlets, understood their lifestyles and the issues they faced and was soon affectionately christened ‘Bhaisahab’ by the community. He set up a small-scale industry in Valsad to remove middlemen.

“On one occasion, a contractor came to me with a gun in his hand, asking me to stop my work. It was then that I knew that I was doing something right,” he said.

At this time, his company was growing to several parts of rural India, having formed a community of over 6,000 weavers so far. In 1999, he separated from his brother, came to Jaipur, and renamed his business as Jaipur Carpets. Meanwhile, the company widened its ambit to start exporting to North America and established Jaipur Rugs Inc, which is now known as Jaipur Living.

However, restarting his business meant that a flurry of challenges came his way. “In the first three years, I lost all my money. I had established a good name in the carpet industry and had developed a false feeling of goodness, what you would call euphoria. I realised that I’d spent the last 20 years or so working in the villages, but now, I had to step up to run a global business. For this, I had to learn new skills, change my perceptions, learn new leadership skills. And so, my learning curve began. This curve has brought me here, today, where I sit before you,” he says.

Jaipur Rugs makes hand-knotted carpets in various designs, such as transitional, modern, geometric, floral, and more. It currently makes these in collaboration with artisans across Gujarat, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Jharkhand. The women mostly work out of home, which means that they don’t have to step out for anything — from the initial step of procuring raw material to the final step of churning out a finished product. All the raw material, as well as the leftover material and finished products, are dropped and picked up by Jaipur Rugs from the weaver’s home itself. The leftovers are used to weave their Manchaha rugs.

Presently, 20,000 women are employed with the company, and around 2,70,000 have been impacted with the help of healthcare, employment, education and more.

Among them is Kamli, who began working with Jaipur Rugs three years ago, and is now not only earning enough but is also fulfilling her dream of completing her education, thanks to the Jaipur Rugs Foundation’s Alternative Education Programme. The initiative began in 2010 to provide functional literacy to the rural community. This six-month programme holds two hour regular classes wherein artisans and others are taught basic literacy and math, made to understand health and hygiene, and given life skills to lead a self sustaining life.

“All my children are also completing their respective high schools and graduate degrees,” Kamli says, and tearfully points out that her new home is currently under construction.

“These women have been able to find dignity and have increased their income,” Chaudhary says. “The women weavers in Bikaner still work on Gandhi ji’s charkha. In a month, they can earn up to Rs 7,000 per month.”

‘Gandhi’ of the carpet industry

When Chaudhary first started recruiting artisans, he faced a lot of resistance because women were not allowed to work. “But the organisation has created such a name for itself over the years, and proven how integral it has been in women’s development, that now they all want to work with us,” he notes. Jaipur Rugs exports carpets to around 60 countries presently, including the US, regions in the Middle East, Russia, and more.

That the carpet industry is so competitive, what makes Jaipur Rugs stand out? “There was a time when the carpet industry had a very bad name. Child labour, exploitation of labour, inadequate pay were rampant. We have transformed that image globally because we went in with the sole aim of rural development. We don’t work with contractors in a bid to eliminate middlemen and deposit money directly in the hands of weavers. They are our family. We help them understand changing [customer] needs so they can deliver better quality even as time goes by. Timely delivery, zero-defect, quality of weaving — these are all factors we keep as utmost priority.”

Among many other programmes, Jaipur Rugs launched Manchaha in 2012, under the vision of Chaudhary’s daughter Kavita. In this project, weavers create their own designs on rugs, which means that the final product is a way of both self-expression as well as livelihood for them. Stories about their lives, their culture, food, colours, animals, music, dreams, and more are stitched into each of these carpets to provide a window into the lives the women lead.

Speaking of what he would call his most triumphant moment over his 43-year-old career, he recalls, “One day in 2008, I was sitting in my office when I received a call from C K Prahalad. I thought he had dialled the wrong number.”

“He was calling me because he wanted to do a case study on Jaipur Rugs’ business model. I asked him, ‘Who will read a case study like that? We’re just simple people carrying out work that no one even knows of.’ He told me, ‘Your global supply chain is connecting the poorest of the poor to the richest of the rich, and enhancing capabilities at the grassroots.’ I felt great when I heard such praise from a man of his stature.”

Presently, Jaipur Rugs is on a mission to “convert all their artisans into artists”. “Our Manchaha project has turned into a global phenomenon. We aim to take it higher.”

Over the years, Chaudhary has gained the title of ‘Gandhi of the Carpet Industry’. When asked how he feels about that, he says, “For me, Gandhi means simplicity. Instead of creating a false identity that was not at par with who I am, I just worked to give people love and respect, and worked hard for it.”

No comments:

Post a Comment