The design of India’s national emblem, the most visible symbol of our country’s national identity, was adopted from the Lion Capital of an Ashokan pillar excavated in Sarnath. On 26 January 1950, the day India became a republic, this symbol was adopted as her national emblem.

Here’s how the Government of India describes our national emblem: “The profile of the Lion Capital showing three lions mounted on the abacus with a Dharma Chakra in the centre, a bull on the right and a galloping horse on the left, and outlines of Dharma Chakras on the extreme right and left was adopted as the State Emblem of India on January 26, 1950. The bell-shaped lotus was omitted. The motto Satyameva Jayate, which means ‘Truth Alone Triumphs’, written in Devanagari script below the profile of the Lion Capital is part of the State Emblem of India.”

Why did India adopt a symbol from the ancient rule of a Mauryan King, Ashoka?

Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister, had some answers for the Constituent Assembly on 22 July 1947, barely a month before India’s Independence.

“For my part, I am exceedingly happy that in this sense indirectly we have associated with this Flag of ours not only this emblem but in a sense the name of Asoka, one of the most magnificent names not only in India’s history but in world history….Now because I have mentioned the name of Asoka, I should like you to think that the Asokan period in Indian history was essentially an international period of Indian history. It was not a narrowly national period. It was a period when India’s ambassadors went abroad to far countries and went abroad not in the way of an empire and imperialism, but as ambassadors of peace and culture and goodwill.”

What do these four majestic Asiatic lions on the national emblem represent?

According to Heritage Lab, “They represent power, courage, pride, and confidence. The Mauryan symbolism of the lions indicates ‘the power of a universal emperor (chakravarti) who dedicated all his resources to the victory of dharma’. In adopting this symbolism, the modern nation of India pledged equality and social justice in all spheres of life.”

Going further, it adds, “The lions sit atop a cylindrical abacus, which is adorned with representations of a horse, a bull, a lion and an elephant, made in high relief…The animals are separated by intervening chakras (having 24 spokes). The Chakra also finds representation on the National Flag. This chakra, or the ‘Wheel of Law’ is a prominent Buddhist symbol signifying Buddha’s ideas on the passage of time. Dharma (virtue), according to belief, is eternal, continuously changing and is characterised by uninterrupted continuity.”

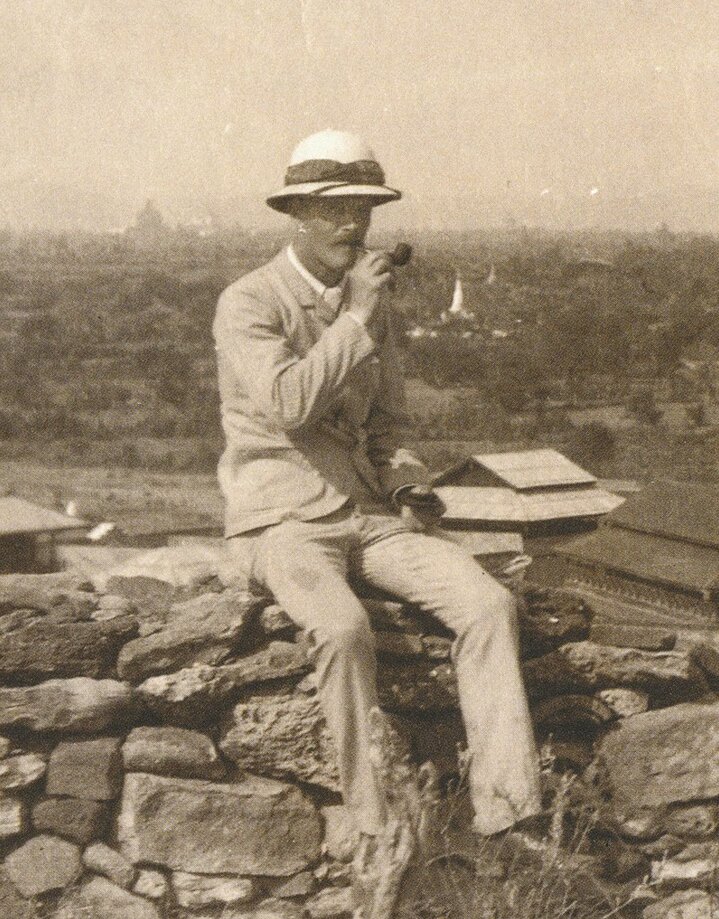

India’s national emblem is a symbol steeped in ancient history. However, we may not have known about this symbol if it wasn’t for the work of a German-born engineer, architect and archaeologist. In the winter of 1904-05, while excavating an archaeological site in Sarnath, Uttar Pradesh, Friedrich Oscar Oertel unearthed the Lion Capital of Ashoka of an Ashokan pillar.

A naturalised British citizen, Oertel’s contributions to Indian art history, archaeology and national identity have been overlooked. After all, he spent most of his time working as a civil engineer and architect in the Public Works Department under the British colonial administration.

Here’s a brief story about the man who would help unearth India’s national emblem.

A man well-travelled

Born on 9 December 1862 in Hannover, Germany, Oertel left for British-ruled India at an early age. Graduating from the Thomason College of Civil Engineering (known today as IIT-Roorkee), he was first employed as an engineer for railway and building construction by the Indian Public Board from 1883 to 1887.

Following his stint here, Oertel returned to Europe to study architecture before making his way back to undivided India. According to Claudine Bautze-Picron, an Indian art historian, “Oertel then started upon a brilliant career in the Public Works Department, being first sent on diverse missions and then appointed in various locations. Sent by the Government of the North-Western Provinces and Oudh, in the winter of 1891–92 he surveyed the monuments and archaeological sites in North and Central India before reaching Rangoon in March 1892.”

Travelling through Burma (present-day Myanmar), which was also under British rule, he wrote a lengthy and detailed report on the monuments of Burma with original photos.

Bautze-Picron would go on to add, “In 1900 he was sent to Sri Lanka by the Royal Asiatic Society in order to visit the Abhayagiri dagoba [a very sacred Buddhist pilgrimage site] and make suggestions on the best way to preserve or restore it.”

“As Executive Engineer in the ‘Buildings and Roads’ branch of the Public Works Department, North-West Provinces and Oudh, as from 1902, and as Superintending Engineer from 1908, he was posted in various places of Uttar Pradesh: from 1903 to 1907, he was in Benares, in 1908 he was located in Lucknow, and from 1909 to 1915, in Cawnpore [Kanpur]; he was then sent to Shillong, Assam, where he remained up to 1920.”

His experience in supervising and constructing buildings during this time, particularly in Uttar Pradesh, helped him “to formulate his opinion concerning the construction of the new capital at New Delhi”. During a lecture delivered at the East India Association at Caxton Hall, Westminster, on 21 July 1913, he urged architects commissioned by the administration to take inspiration from a “really national Indian style” while designing the new Capital city.

‘Unearthing’ the national emblem in Sarnath

However, Oertel is best known for the excavation he carried out on Sarnath from December 1904 to April 1905. Writing for Live History India, Janhavi Patgaonkar notes how “in the early 19th century, Sarnath began to attract the attention of scholars for its archaeological significance”.

First explored in 1815 by Colin Mackenzie, the first Surveyor General of India, Sarnath would witness further excavations in the 1830s by Alexander Cunningham, who would go on to become the Director General of the Archaeological Survey of India.

There was a great deal of interest in Sarnath, and Oertel naturally caught onto it. Serving in Benaras at the time, Oertel secured permission to excavate a site in Sarnath. In the following year, he began his work with assistance from the Archeological Department.

According to Patgaonkar, Oertel unearthed “some of the most significant discoveries ever made” in Sarnath. These include “476 sculptural and architectural remains, along with 41 inspirctions”. She adds, “A figure of a Bodhisattva dated to Kushana King Kanishka (r. 78-144 CE), the foundation of a Sangharam (monastery), several images of Buddhist and Hindu deities, and Ashoka pillar bearing the edicts (inscriptions) of Mauryan Emperor Ashoka (3rd BCE)”.

Of course, the most significant discovery was the Lion Capital which crowned an Ashokan pillar (hence the term ‘capital’). This particular pillar was one among the many commissioned by Ashoka across the Indian subcontinent used to spread the message of Buddha after he had converted to Buddhism. The Lion Capital discovered in Sarnath is “among only seven capitals of Ashokan pillars that have survived”, notes Patgaonkar.

Here’s how the ‘Archaeological Survey of India: Annual Report 1904–1905′ describes this finding, “The capital measures 7’ [feet] in height. It was originally one piece of stone, but is now broken across just above the bell…it is surmounted by four magnificent lions standing back to back and in their middle was a large stone wheel, the sacred dharmacakra symbol.”

The report goes on to add, “It apparently had 32 spokes, while the four smaller wheels below the lions have only 24 spokes. The lions stand on a drum with four animal figures carved on it, viz., a lion, an elephant, a bull, and a horse, placed between four wheels. The upper part of the capital is supported by an elegantly shaped Persepolitan bell-shaped member. The lion and other animal figures are wonderfully life-like and the carving of every detail is perfect.”

Describing its majesty, the report noted, “Altogether this capital is undoubtedly the finest piece of sculpture of its kind so far discovered in India…Considering the age of the column, which was erected more than 2,000 years ago, it is marvellous how well preserved it is. The carving is as clear as the day it was cut and the only damage it has suffered is from wilful destruction.”

The Lion Capital was found buried near the Dhamek Stupa at the site. While the pillar today stands in the location where it was found, the Lion Capital was shifted to the Sarnath Museum.

Despite such a significant discovery, Oertel could only excavate Sarnath for only a season, and by 1905 was transferred to Agra. Following the famine in the United Provinces in 1907-08, he was refused permission to come back and organise further excavations at Sarnath.

Fortunately, scholars like BC Bhattacharya haven’t forgotten Oertal’s contributions at Sarnath. “The excavation of Oertel ushered in a new era in the annals of research work at Sarnath. The world is indebted to him for the wonderful discoveries made by him at this place.”

From Sarnath, Oertel left for Agra, where among other works, he undertook the restoration of the “Diwan-i-Amm and Jahangiri Mahal in the Agra Fort and the reconstruction of the four minarets of the south gateway of the Akbar tomb in Sikandra in 1905–1906 while also working on the compound of the Taj Mahal,” notes Bautze-Picron. He would also conduct a more detailed study of Mughal architecture, and by the end of the decade “documented the sculptures of Yoginis at Rikhian (Rikhiyan) in Banda, now Chitrakoot district of Uttar Pradesh”.

When Oertel left India for the United Kingdom in 1921, he probably had no idea that his work would lay the basis of India’s national identity following freedom from British rule. There is little information about his death, but the legacy he leaves behind is there for all Indians to see.

(Edited by Yoshita Rao); (All images courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

No comments:

Post a Comment