There are some films that leave their mark in time, and Shyam Benegal’s Ankur (1974) is one classic example. The film’s achievements extend beyond the confines of bagging three National Awards. Through its gripping storyline, it sparked debate about the caste system and its evils in India through the optics of those most victimised by its effects.

The film highlights the arc of emotions that Lakshmi (a Dalit woman living in rural Andhra Pradesh and essayed by Shabana Azmi) goes through as she begins working for an upper-caste zamindar’s son Surya, who does not delve too much into the caste difference. The movie brings to the front issues of patriarchy, caste, class and gender in a tale that is both beautiful and sad.

Over the decades, Indian cinema has touched upon the pervasive caste system in India through many films — some deemed controversial yet milestones, like The Bandit Queen; some that resonated with wider audiences like Article 15 and Jai Bhim; and some that used humour to comment on the gravity of caste discrimination, like Chameli ki Shaadi.

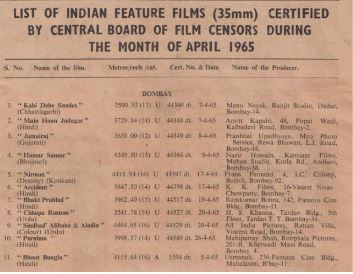

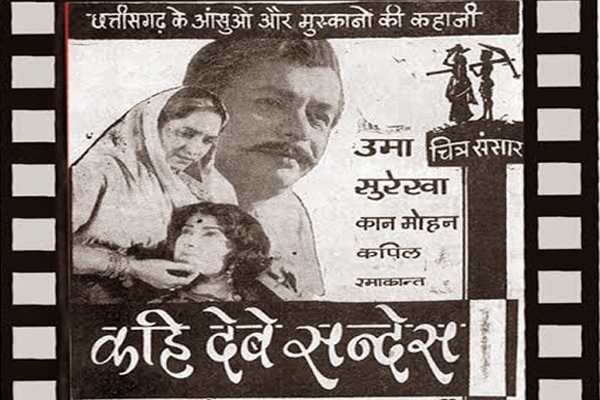

Among the films that set the precedent for these movies was the seemingly obscure production Kahi Debe Sandesh, a Chhattisgarhi film released in 1965, which became among the first in India to openly discuss evils like untouchability and caste discrimination.

In a 2018 interview with filmmaker and documentary photographer Aayush Chandrawanshi, the director of the film Many Nayak recalled, “I was very determined to make a film in the Chhattisgarhi dialect and to name it Kahi Debe Sandes. I had a theme in my mind which was inspired by my childhood experiences.”

What made Nayak’s film so remarkable was its willingness to take on the matter of inter-caste marriages — something that is still discouraged and frowned upon in many parts of the country. In many ways, it was among the first artistic pieces of work to open conversation about topics we still skirt around today.

A film ahead of its time

Meanwhile, in the early 1960s, the Indian film industry was dominated by Hindi-language movies, thus providing little to no opportunity for regional script movies. This spell ended in 1963 with Kundan Kumar’s Bhojpuri film Ganga Maiya Tohe Piyari Chadhaibo, a poignant film on widow remarriage. In Madhya Pradesh, a young film enthusiast Manu Nayak was so influenced by this that it compelled him to make a Chhattisgarhi film on a subject that he was passionate about.

Directed by Nayak and released in 1965, Kahi Debe Sandesh was the talk of the town for more reasons than one. Not only was the film’s plot considered controversial, but it was also the first film in the Chhattisgarhi language at a time when the film industry was dominated by Hindi films. It must also be remembered that this event was much before Chhattisgarh came into existence as a state in 2000.

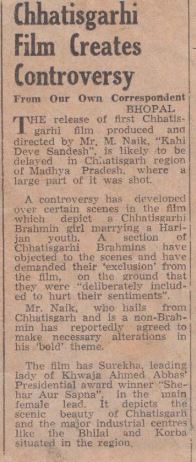

The film detailed the love story of Nayandas and Rupa, a boy from a scheduled caste and a Brahmin girl respectively. The storyline faced the ire of conservatives and leaders across the nation, notably from the Brahmin community in Raipur. Nayak recalled, “All of a sudden there was a controversy, where a section of the Brahmin community accused the film, saying that it disrespects their community. They protested the release of the film in Raipur….”

As these groups forced posters of the movie to be taken down, many prominent voices spoke up against this. One of them was former prime minister Indira Gandhi. Nayak later recalled in an interview to The Times of India that help came from two “progressive” politicians. “I was told Indira Gandhi (then I&B Minister) also saw portions of the film and said the film promotes national integration. The protests died down after that.”

The crew powered through the backlash and managed to have the film premiere in April 1965. Ironically, the hullabaloo that the film created drew more attention with people flocking to cinema screens to catch it. It opened the windows for society to take cognisance of the evils of the caste system.

In fact, the film also served as the launchpad for Chhollywood (as the film industry of Chhattisgarh is popularly known) and was screened in Raipur in 2015 at a film festival to mark the jubilee of this event. For Nayak, this event held tremendous significance.

Behind the scenes

While Kahi Debe Sandesh blew up the film industry with conversation about films centric on social issues, Nayak had never in the slightest imagined it would have this effect. In 1957 a teen Nayak had run away from his hometown Raipur to Bombay with a dream to work in films. His interest in cinema came from his growing years of browsing through film magazines at local stands, a task he said kept him up to date with the world of movies.

As fate would have it, he landed a job with Anupam Chitra, a film production house that was co-owned by director Mahesh Kaul and writer Pandit Mukhram Sharma.

It was here that he learnt to copy dialogues in Hindi, while learning the fineries of script writing from the maestros. With a salary of Rs 60 per month and unparalleled satisfaction, Nayak dreamt of making a movie someday.

Chandrawanshi wrote that Nayak’s motive behind making this film was as follows — “Kahi Debe Sandes (1965) is a commentary on social issues such as Untouchability and Caste discrimination. I had seen it happening even in my own house. Whenever my friends from the lower castes (Satnami caste) used to come to my home, my mother used to not say anything but soon after they had left she used to clean the entrance of the house. This and a few other instances deeply affected me and I realised that until caste discrimination is addressed properly to the masses, society would not progress.”

And so intent on these issues seeing the light of day, Nayak began his quest of casting.

Following a song recorded with legend Mohammed Rafi — Jhamkat nadiya bahini laage — a quick casting of theatre actors who were willing, and a record 22-day packed shoot schedule, Kahi Debe Sandesh was ready to roll.

As Nayak says in an interview with The Times of India, “I spent the next two years paying off my debts. But I had the satisfaction of making the first Chhattisgarhi film.”

Today, the film continues to stand by its legacy of being among the first to shed light on caste discrimination.

Indian cinema has come a long way in terms of the narratives highlighted in caste movies, as Sanjiv Jaiswal, director of Shudra (2012) emphasised in an interview with Outlook India. “When we dare to make films like these [Shudra], we are able to put the spotlight on the discriminated communities. There is a marked shift in how these movies are made today. The storylines give the communities depicted greater agency and power over the story. This is a big change from the past, when either their entire existence would be ignored, or portrayed in poor light, causing more harm than good for these sections.”

Edited by Divya Sethu

No comments:

Post a Comment