When we speak of the role of Indian men and women in shaping the medical world, one of the most compelling stories that come to light is arguably that of Kishori Mohan Bandyopadhyay and his role in the fight against malaria.

The science graduate’s work in tackling the disease, while celebrated by the scientific community, was not awarded the Nobel prize. But this did not deter him from furthering his quest to educate people about the parasite-transmitted disease, and the precautions they must take to avoid contracting it.

Two great minds bond over an idea

Born in Kolkata in 1877 to a family of educators, Bandyopadhyay was an avid learner. Keen to explore the world of science with its many mysteries, he opted for a graduation in science at the Presidency College and emerged with flying colours in 1898.

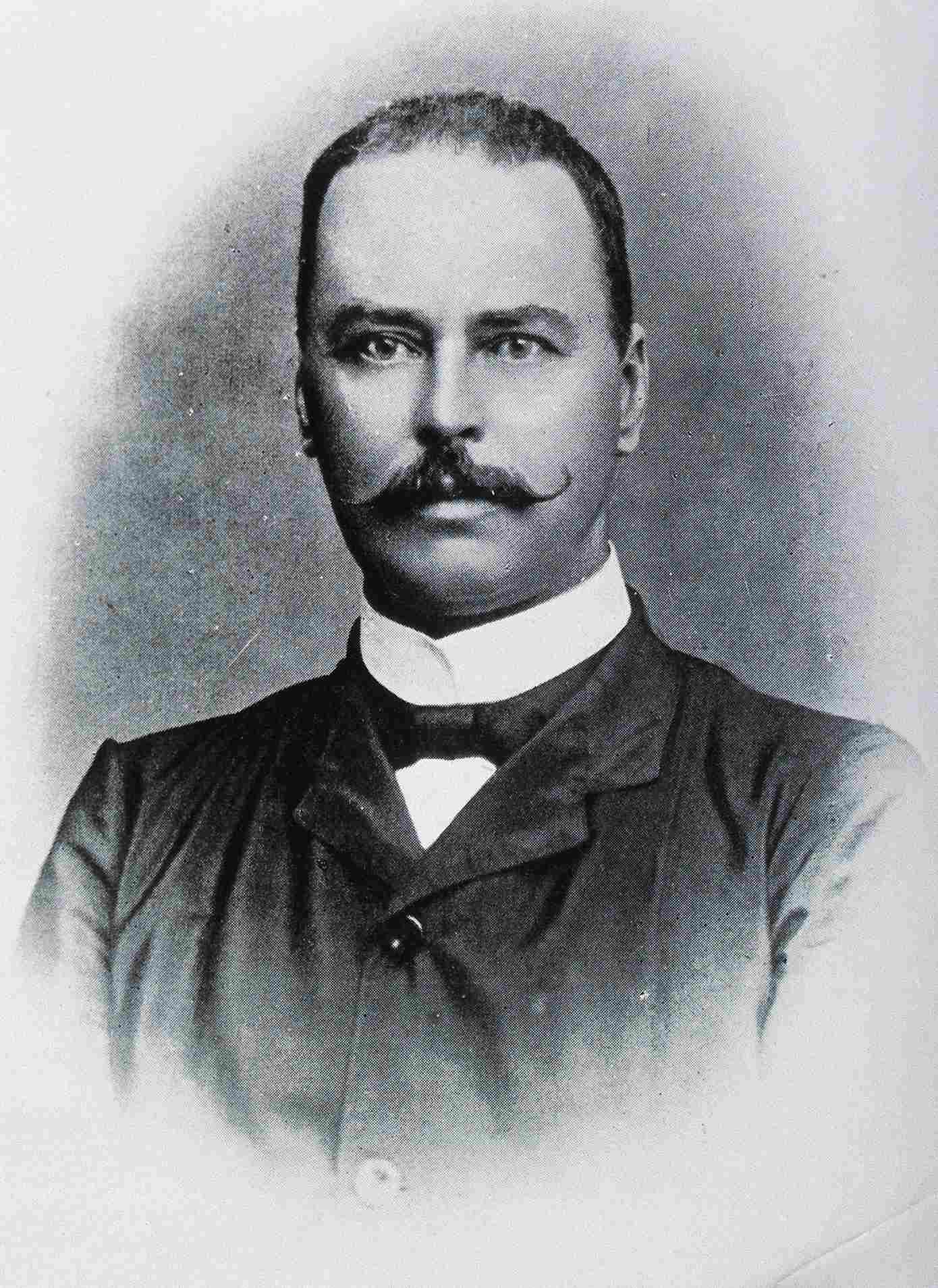

Bandyopadhyay was hungry to pursue scientific research that had the potential to help his nation and began looking for opportunities. This was around the same time that Sir Ronald Ross — a British medical doctor who later received the Nobel Prize in 1902 for his work on the transmission of malaria — was in Kolkata.

Following years of medical studies in London, Ross joined the Indian Medical Service in 1881 on the advice of his father, a General in the Indian Army. It was in 1892 during his various engagements with doctors and people from the medical community that Ross displayed an interest in malaria — specifically its mode of transmission from parasites to humans.

Greatly influenced by Patrick Manson, the founder of tropical medicine, Ross began to explore this new arena of interest, marvelling at how a parasite could cause human disease by infecting a mosquito. Armed with this awe-evoking information Ross began his work on proving that malaria was connected to mosquitoes in 1895.

While on the lookout for an able assistant, he came across the keen Bandyopadhyay who was looking for work as a lab assistant. In 1898, the two bonded over this passion project, and soon, it was a done deal.

Bandyopadhyay would assist Ross.

The years spanning between 1898 and 1902 were brimming with research ideas that the two men of science had. While Ross would get excited over new developments in their quest to prove the relationship between mosquitoes and malaria, Bandyopadhyay made maximum use of his abilities in regional languages.

The study necessitated testing the blood of malaria patients, observation and dissections of the female Anopheles mosquito, etc, and Bandyopadhyay would put his skills to the test. He would regularly visit the neighbouring villages of Kolkata and Madras in search of patients with malaria and bring them back to Ross’ lab. Here, the latter would collect blood samples from these people.

These real-time experiments proved to be a boost for Ross’ research. And by 1899, he had not only discovered the role of the female Anopheles mosquito as a vector in the transmission of malaria to humans but also stumbled upon the transmission cycle of the disease in birds.

A missing acknowledgement

Meanwhile, Bandopadhyay’s work with malaria did not stop at the lab.

He would propagate the use of mosquito nets in the surrounding villages so as to caution people about the condition and prevent them from contracting it. He would frequently conduct social campaigns in the villages. And along with his photo artist friend, Lakshminarayan Roychowdhury’s help, he would make public slide shows to educate the villagers about spotting the difference between different mosquitoes so as to identify the female anopheles.

The year 1902 saw a proud moment for medicine as Ronald Ross was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology “for his work on malaria, by which he has shown how it enters the organism and thereby has laid the foundation for successful research on this disease and methods of combating it”.

But while the scientific community cheered the efforts of Ross, one man remained forgotten. Bandyopadhyay’s hard work remained unrecognised.

This did not sit well with many notable names of the time, who went on to raise their concerns about this. Among them were Indian physician Upendranath Brahmachari, writer and polymath Acharya Jagadish Chandra Bose, philosopher Brajendra Nath Seal, social reformer Sivanath Sastri, political figure Surendranath Banerjee, and historian Acharya Prafulla Chandra Ray.

They requested the then Viceroy of India Lord Curzon that Bandyopadhyay be awarded for his efforts, and the Viceroy obliged. In 1903, Bandyopadhyay was awarded King Edward VII’s Gold Medal and felicitated at the University Senate Hall.

In 1918, when a malaria epidemic struck the country, Dr Gopal Chandra Chattopadhyay started a public health movement to control the spread, and Bandyopadhyay joined him.

They began educating the villagers about sanitisation and good hygienic practices. The Anti-Malaria Cooperative Society was founded for the first time at the village level in India at Panihati on 24 March 1918. Bandopadhyay was the secretary and was at the helm of activities that encouraged cleaning ponds and drains in the village, clearing the garbage that choked the lakes and distributing mosquito nets. This compelled other villages to start similar associations to curb the spread of malaria.

Notable author Amitav Ghosh’s book ‘The Calcutta Chromosome’ details bits of Ross’s journey while shedding light on his research phase. The book is said to question the boundaries that have been erected to distinguish truth from fiction and also points to how Bandopadhyay’s knowledge played a role in Ross’s success.

Following the disappointment at not finding mention in Ross’s work, Bandopadhyay went on to start The Panihati Cooperative Bank in 1927, two years after which he passed away. Today, as there have been several strides in the prevention and cure of malaria, we remain indebted to Kishori Mohan Bandyopadhyay for his tremendous contribution.

No comments:

Post a Comment