In 1917, when British rule prevailed over India, the government prepared a list to keep track of 32 of MK Gandhi’s closest associates. At number 10 was a name that history hasn’t forgotten since.

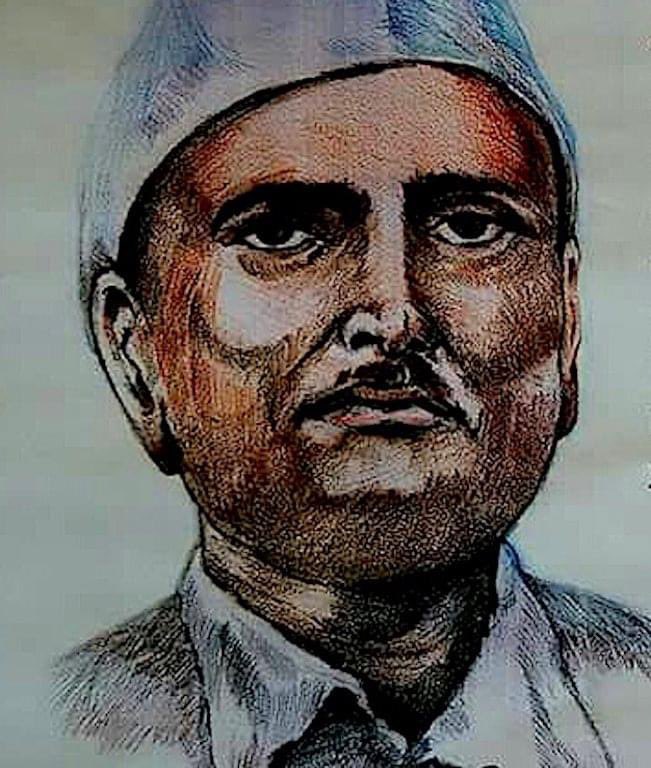

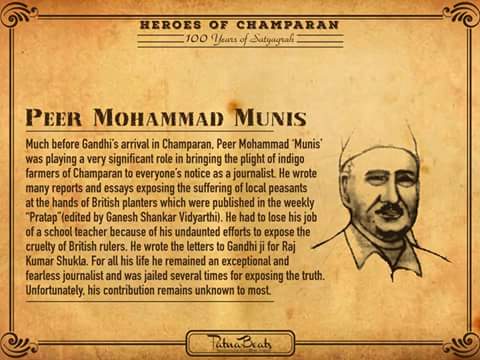

Pir Muhammed Munis, a journalist known for the power of his pen, was instrumental in his role in the Champaran Satyagraha movement, also touted as India’s first organised act of civil disobedience.

Through his body of work, he scripted a record of heroism that is etched into the sands of time.

To truly appreciate Munis’ role in the struggle for Independence, we trace our steps to 1916, when the British Raj was exercising exceeding control over Indians. One particularly vulnerable group were the farmers in Champaran, Bihar.

The source of contention was the agrarian practices in the region. While the British were intent on the peasants growing indigo, a lucrative cash crop with sizable demand in the markets abroad, the farmers were deprived of land for growing food crops instead. This tussle culminated in a famine, causing the farmers to rise in revolt against the dominion of the British. As the conflict escalated, word reached Gandhi. How?

Pir Muhammed Munis was behind it.

A ‘rouge journalist’

The uprising of the peasants in Champaran wasn’t going unnoticed. The country was reading about it thanks to Munis, who left no stone unturned in letting his views reflect his patriotic feelings. In the years to come, Pir Muhammed Munis would go down in history as the journalist who raised his voice when it was most difficult to be heard.

He chronicled the efforts of the farmers, the unlawful practices of the British and more such news in Hindi — despite the elite class being fluent in Urdu, Persian and English — displaying his ardent love for the language. In his later life, he went on to advocate for Hindi to be propagated amongst the masses. Anecdotes suggest during his later interactions with Gandhi, Munis even went on to teach the legend the language, a skill that greatly helped the latter.

So persistent and vocal was he about his patriotic opinions that he was termed as “notorious”, “bitter” and “dangerous” by the British, eventually being branded as a ‘badmash patrakar (rouge journalist)’.

A British Police document from the Azadi Ke Deewane Museum at Red Fort reads, “Pir Muhammed Munis is actually a dangerous and hoodlum journalist who through his questionable literature, brought to light the sufferings of a backward place like Champaran in Bihar.”

The letter that set the stage for the uprising

But nothing stopped Munis from continuing to write, his pen a double-edged sword. His works appeared frequently in Pratap, a Hindi weekly, and monthlys such as Gyanshakti and Gorakhpur. He was also on the editorial board of Desh launched and edited by Dr Rajendra Prasad.

The most famous letter among his repertoire of literary works is a letter he penned with local farmer Rajkumar Shukla, intended to be sent to Gandhi on 27 February 1917. Shukla conveyed the grievances of the farming community, while Munis coupled this with his power of words. An excerpt from the letter reads, “Our sad tale is much worse than what you and your comrades have suffered in South Africa”.

In another letter dated 22 March 1917, Munis once again voiced his concerns about the peasants in Champaran, and asked Gandhi to pay them a visit. And when he did on 10 April 1917, people commended the bond between the two, often calling Munis Gandhi’s pillar as he hatched plans for the Champaran Satyagraha.

As the first Satyagraha movement, it set the stage for future mass protests and uprisings. Gandhi set up schools in the Champaran area, gathered volunteers, conducted village surveys, organised protests, and strikes, and advocated for control over the sale of crops to be given to the farmers. And through this mutiny, Munis was by his side.

This did not go down well with the British. As a letter written by W H Lewis, sub-division officer to the commissioner of Tirhut division indicates, “… Mr Gandhi got offers of assistance, the most prominent is Pir Muhammad. I have not (sic) full details of his career, but either Whitty or Marsham could give them. He is, I believe, a convert to Muhammadanism and was a teacher in the Raj School. He was dismissed from his post for virulent attacks on local management published in or about 1915 in the press. He lives in Bettiah and works as a press correspondent for the Pratap of Lucknow, a paper which distinguished itself for its immoderate expressions on Champaran Questions… Pir Muhammad is the link between this Bettiah class of mostly educated and semi-educated men and the next class, i.e. the Raiyats’ own leaders…”

The result of the tyranny

History never forgets the cries of the just, and the Champaran Satyagraha was proof of this.

The mutiny ended with the British officers agreeing to formulate the Champaran Agrarian Act of 1918. The Act abolished the forcible cultivation of indigo and thus relieved tremendous pressure being put on the farmers here. The event has gone down in history as one of the first major revolts that forced the English to introduce a Bill in favour of the Indians.

With the Tinkathia system being abolished, the farmers thought the worst was over. But the British continued to oppress them in different ways. Fuelled by ending this once and for all, Munis started Raiyati Sabha, a platform that would advocate for and protect the rights of the farming community. For this, Munis faced a six-month jail term.

This wasn’t the last of imprisonment. In 1930 he was imprisoned in the Patna Camp jail for three months for his participation in the Salt Satyagraha of the Civil Disobedience Movement.

However, nothing could deter him from his goal of protecting the rights of his countrymen. In 1937, he led sugarcane producers who were protesting against intermediaries who were pocketing a major part of the earnings. He was also elected member of the Champaran Zila Parishad (District Board) on the Congress ticket and became President of Bettiah Local Board, from which he resigned to join the Individual Civil Disobedience Movement.

Throughout his lifetime, he advocated for rural development, popularisation of Hindi in primary schools and the rights of his fellow Indians. Until his passing away on 23 September 1949 Munis continued to be a leader worth looking up to for his countrymen.

Lauding the efforts of Munis on his passing away, Pratap editor Ganesh Shankar Vidyarthi, wrote in his newspaper, “We have the utmost sorrow that Pir Muhammed Munis of Bettiah, Champaran district has died. We have the privilege to see such souls who are quietly lying aside. The world doesn’t come to know anything about their issues. The lesser these sons of Mother India are renowned, the more profound is their work, the more philanthropic.”

He further wrote, “You recited the dreadful story of Champaran to Gandhi ji and this was a result of your hard-work only that Mahatma Gandhi visited Champaran which made this land a pious place and the place which is unerasable in the pages of history”.

No comments:

Post a Comment