Dr Pramila Sanjaya has lived in Jaipur for over 60 years. Through this time, she has watched the city grow and expand over existing villages.

“What used to be farms have now been converted into colonies and taken over by multistory buildings,” she says. “What I have also witnessed is the growth of informal settlements and slums across the city, which did not exist during my childhood.”

Prateek Tiwari, another Jaipur resident and CEO of Living Greens Organics Pvt. Ltd, also recalls a time when the city centre was full of trees. “When I’d visit my grandparents in Jaipur during May, summers weren’t something we would dread. Of course, we’d stay indoors between 11 am and 3 pm — when it was very hot — but by the evening, the temperature would drop and it would be pleasantly cool, enough for us to sleep on the terrace at night.”

“We no longer have those spaces that helped keep the city cool. Jaipur has changed and it’s not for the better,” he opines.

Jaipur is only one among the several Indian cities facing rising incidents of extreme heat and water scarcity. Meanwhile, coastal cities like Kochi and Mumbai are struggling with urban flooding. Frequent heat waves and urban heat islands trap heat in neighbourhoods, giving residents little relief, even at night.

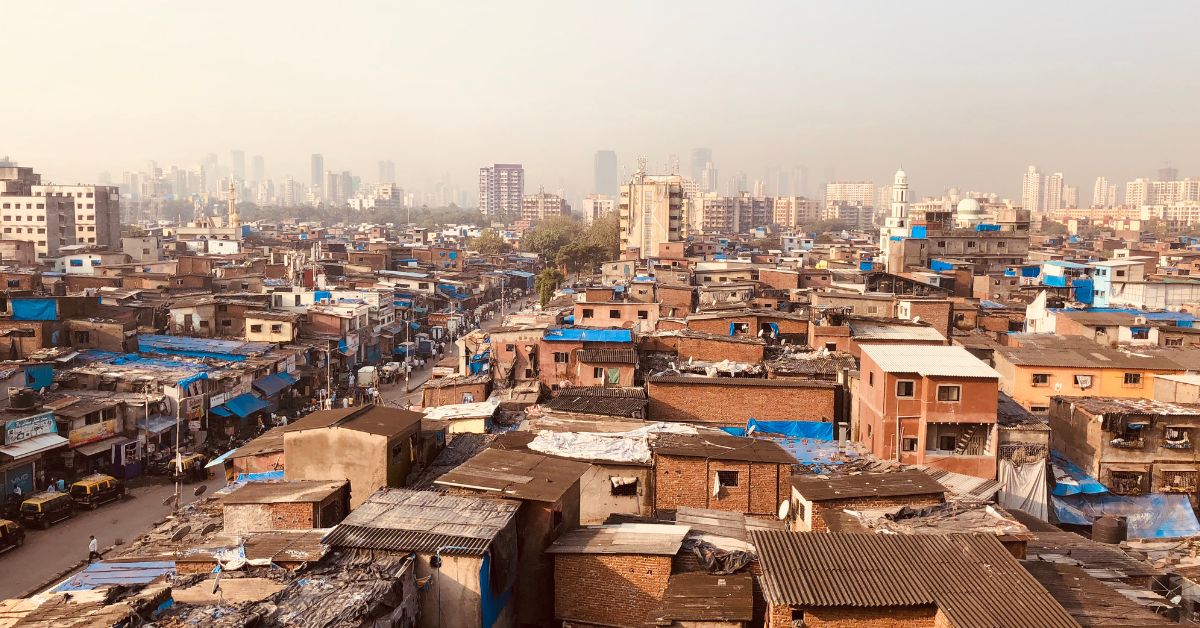

Heat impacts vulnerable communities the most due to the usage of unsuitable housing material such as tin sheets and lack of green cover. In Mumbai, for example, the slums in Dharavi are almost 6 degrees hotter than the better-shaded and more affluent neighbouring locality of Matunga.

In this scenario, working with low-income neighbourhoods at the intersection of high vulnerability to heat and flooding has become imperative. With this in mind, The World Resources Institute (WRI) India has been piloting different Nature-based solutions (NbS) aimed at making communities more resilient to climate change.

NbS interventions not only improve urban environmental ecosystems, but also offer social and economic benefits to communities by creating healthy spaces for recreation, and by opening up opportunities for skilling up and livelihood generation.

Why are low-income groups so much more vulnerable?

Dr Pramila — who is a community organiser and advisor at SIDART, an organisation that works for the upliftment of women and children — says that water scarcity is also one of the biggest challenges of the city, and flooding during monsoons has now become extremely common. “Urbanisation has impacted natural biodiversity, with a lot of forests and hills being cut down,” she explains.

These rising fluctuations and climatic changes affect low-income groups due to a combination of socio-economic and demographic factors. During the 2005 Mumbai floods, over a million slum residents were stranded. These are the neighbourhoods that often lack access to basic services and amenities like potable water, energy, sanitation. For instance, 84.9% of Mumbai’s M-East ward population lives in slums, and only 53.6% of these households have access to water on site.

Then there are the political factors, including the ability of these communities to participate in governance processes, raise their concerns and have them addressed. Vulnerable communities are not involved in sabha (committee) meetings or any community engagements, which results in their concerns not being addressed during the decision-making process. On average, more than 50% of all vulnerable communities surveyed suggested that improvements from the government are needed in terms of health, sanitation, flood prevention infrastructure and other general infrastructure. As much as 60% of the population takes water from public wells and does not have access to water connections.

Dense concrete and impermeable surfaces, taking the place of natural infrastructure like water bodies, green cover and open spaces, have also impacted the ability of cities to manage water runoff during heavy and erratic rainfall patterns, resulting in devastating instances of flooding.

This is where nature-based solutions play an important role.

In Kochi, for example, 12 sites that are prone to flooding and dumping have been turned into urban forests through the Kochi Municipal Corporation’s Kawaki initiative. These erstwhile mosquito breeding grounds are now seeing the scientific plantation and maintenance of saplings, which as fully grown trees will offer much needed heat mitigation through green cover and permeable surfaces that can absorb rainfall and help recharge groundwater.

The municipal corporation, under the Ayyankali Urban Employment Guarantee Scheme (AUEGS), trained over a hundred workers on the maintenance of the urban forests and are teaching them how to prepare the soil for sowing, plant saplings, water and weed the area, and build low-cost tree guards to protect the saplings from animals.

Speaking about the implementation of this programme in her own neighbourhood, Sindhu Jayan, a worker with the Ayyankali Scheme, notes, “This work has been very different, and we are very glad to have learned these new skills. The deserted graveyard was a scary and unwelcoming place, but we have been able to turn what will be our final resting place into a beautiful grove.”

Meanwhile, in Jaipur, WRI India is working under the Cities4Forest project with local institutions and Living Greens to develop urban farms. Four of these are on school rooftops — including a school for the blind and for children living with HIV, as well as a primary school in a low-income neighbourhood — while one is inside a prison facility. Such community-based projects are building skillsets around urban farming and tree-and-plant care. For instance, the prison inmates in Jaipur have been trained in the basics of organic farming that can serve as valuable and marketable skills should they choose to pursue associated livelihood opportunities after their release.

Hanuman, secretary of Mamta Public School, found the project to be full of potential, notwithstanding a few challenges.

“The importance of this project was to gain a first-hand understanding of what rooftop farming looks like and how it can help, with the intent that students learn something new and grow food on their own.”

He continues, “While community members were always interested in farming, this project provided an opportunity for them to take it up in their own homes. They found this to be a unique learning experience. Our students, too, were surprised to know that rooftops could be used in such a manner too. Of course, managing the rooftop space has its own challenges; the children sometimes wish to use the space for other purposes such as events and celebrations. Overall, I think the project has a lot of potential. An entire family of four can be fed with the harvest from the intervention.”

Scouts & Guides District Training Centre, in Powai, Mumbai, is home to a thriving food garden spread across 2000 sq. ft., piloted under ‘TheCityFix Labs India Nature-based Solutions (NbS) Accelerator’, a Cities4Forests initiative. The head of this institution, Alka Pawar believes that such training also builds the character of future citizens and encourages interest towards farming. “Our students will come to know about different vegetables and plants, and it will develop their self-confidence and instil a dignity of labour among them” she points out.

Similar urban farming interventions have been carried out at the Mumbai Public School, and the Collectors Colony School Building, Chembur, under the accelerator. The school students and staff are directly involved in the maintenance of these farms, allowing them access to green spaces and to grow a local supply of food.

What to keep in mind while choosing NbS

Opting for nature-based solutions, however, requires foresight and meticulous planning. It needs careful consideration of the availability of time and space; the cost of each solution at the time of implementation and over its lifetime; the skill required to maintain the solution; and the potential incidental benefits worthy of investments.

Urban forests, for instance, require at least three years of care before the trees are fully grown and the spaces become self-sustaining ecosystems. The selection of trees, too, must consider the appropriate native species, the urban context such as the availability of water, and the presence of overhead and underground cables and drains.

A shed, on the other hand, can be constructed quickly and can provide shade. However, it will lack the co-benefits of managing rainfall and providing a habitat to the local biodiversity, as well as the aesthetic appeal of a tree. Ultimately, the competition over space and resources may not be able to choose between a nature-based solution or grey infrastructure, but instead it must see how well both can be integrated to shape more resilient cities.

The communities at the heart of these projects can also play the critical role of building a strong case to prioritise and institutionalise such solutions in the long-term adaptation plans of cities. The jail in Jaipur is now seeking funding to potentially scale the urban farming program to nine other central jails across the state, while Mumbai’s Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) is expanding the school rooftop farming programme to 250 schools across Mumbai.

Urban India can consider promoting NbS at scale and can glean practices from other cities around the world that face similar climate change challenges. However, mainstreaming NbS as a means to address climate risk is often sidelined, as there is still limited ability or willingness to look at alternatives to grey infrastructure. Shaping a more sustainable and resilient future will need not just financing, but also a shift in mindsets starting with the policies that govern urban development.

WRI India works with local and national governments, businesses, and civil society to address India’s development challenges.

Written by World Resources Institute, India; Edited by Divya Sethu

No comments:

Post a Comment