Around six years ago, Aditya Chaudhary recalls his favourite part of the day as rushing home to his grandfather after school. The duo would spend the rest of the day together. Now an ex-student of Delhi’s Shaheed Rajpal DAV Public School, Aditya (17) fondly reminisces over those times.

In the uninterrupted hours they had until Aditya’s parents returned from work, the duo made some great memories. The fondest of these, according to Aditya, were their daily chit-chats. But in 2017, their world shifted following his grandfather’s Parkinson’s disease diagnosis.

In the years that followed, the condition rapidly advanced. The stiffness in muscles coupled with difficulty in talking put a damper on the daily activities that the two had come to enjoy. “It was around 2020 that he found even basic conversations tough,” Aditya shares, adding that his grandfather passed away in 2021.

The grief of losing a grandparent, one who had grown to be close company, was coupled with introspection. “I wish in those last days I could have understood what he was trying to tell me,” the grandson explains.

For someone who spent hours in his school’s ATL (Atal Tinkering Lab) — labs set up in schools across India to foster curiosity among students — Aditya was now driven by a new afflatus, one that involved coming up with an innovation to help patients with Parkinson’s disease.

The ache in him to do more for society built a roadmap to innovation, one that eventually led to Aditya’s ‘Kalam’ initiative in early 2023, which aids students in India with information about funding, scholarships, grants and more.

When ingenuity fills gaps

For the next several months after his grandfather passed away, Aditya barely emerged from his room and the lab. But when he finally did, it was with a research report — one that won acclaim from The Hong Kong Academy of Sciences — and a prototype device he called the ‘NeuroSight’.

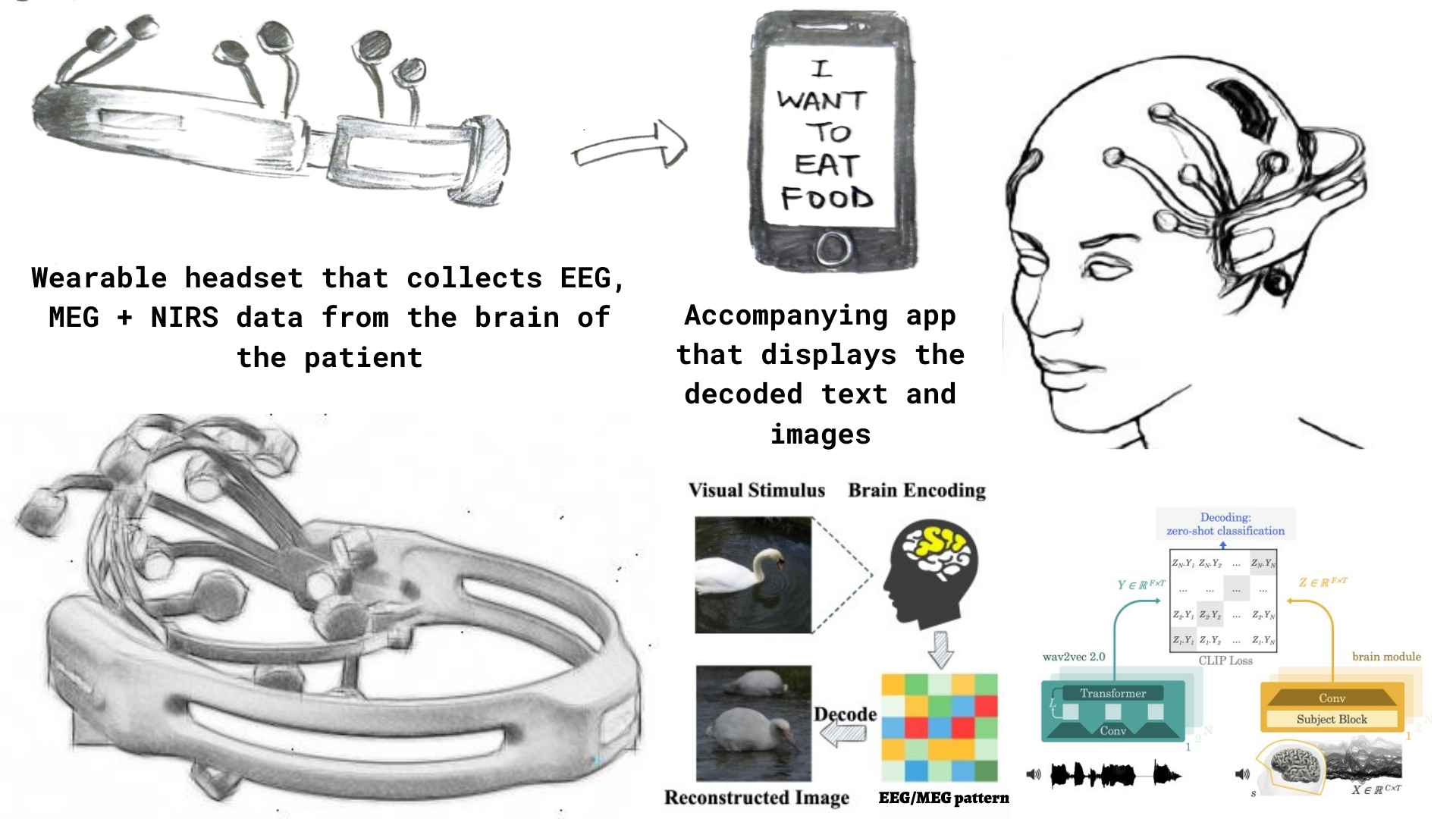

The non-invasive headset would one day help paralysed and neurological patients convert their thoughts into text and images, he postulated.

NeuroSight prides itself on the science of neuroimaging, which is a branch of medical imaging that assesses brain health. By deploying a host of microcontrollers, sensors and electrodes, it collects information from the patient and relays this to an app that the family member can download. Through a real-time processing module, the patient’s thoughts are converted into text.

NeuroSight and its potential were recognised by Aditya’s school much before it made it to international platforms. Vineeta Garg, the head of the department of computer science at Aditya’s school commends the device for its multifaceted approach.

She notes how people with various kinds of neurological conditions can be helped. “A patient who has had a stroke can use NeuroSight to control a robotic arm, while a child with cerebral palsy could use it to play video games.”

But that said, she notes the best feature of the device is being able to deliver “high technological assistance even with low-level neuroimaging”. This is possible due to AI integration, she adds.

When one idea leads to another

Every new project that Aditya undertakes has an undertone of impact to it. So, even his second innovation ‘VacciVan’ — which he came up with in 2021 on the heels of NeuroSight’s success — was in a bid to help.

During the second wave of COVID-19, Aditya chanced upon a World Health Organisation (WHO) report that highlighted shocking figures, ones that formed the base for VacciVan.

Sharing these, he says, “The report suggested that up to 50 percent of vaccines are wasted globally every year because of lack of temperature control and logistics to support an unbroken cold chain.”

If only there was a way to ensure optimal temperatures during the last-mile delivery, he thought. Once again the ATL Lab at school was occupied for hours in the months to come.

The result that Aditya produced this time was a thermoelectric device that offered controlled refrigeration. Called VacciVan, the “novel low-cost vaccine transportation and storage system” is powered via bicycle pedalling. This eliminates the need for ice packs or external electricity.

Aditya elaborates on the mechanism, “When the bicycle is pedalled, current is generated through electromagnetism. The current is then stored and used to freeze the vaccines at the designated 2-8 degrees Celsius.”

Calling the innovation “a remarkable solution to a critical issue”, the headmistress at Aditya’s school, Vinita Kapoor, applauds him for his ingenuity. “VacciVan’s versatility can benefit not only healthcare but also food security in low-income or remote areas with unstable electricity supplies,” she notes while talking about its potential once it is scaled.

The innovation not only propelled Aditya closer towards his goal of solving societal issues but also gave him financial impetus. VacciVan was finalised by the jury at Oxford University’s Rhodes Trust and Schmidt Futures, the initiative by Eric Schmidt, Google’s former CEO, for a scholarship and $10,000 prototype grant.

It was also selected by the department of science and technology of the Indian government for prototype development in Inspire-MANAK. This flagship programme fosters a culture of creativity and innovative thinking among school children aged 10-15 years.

Things were now looking up and Aditya decided to apply for the ISEF 2022 (International Science and Engineering Fair) which is also the world’s largest international pre-college science competition. But, he recounts, “I couldn’t apply. A prerequisite was to first compete in the IRIS National Fair held in India.”

This disappointment led him to another revelation. Despite the scores of opportunities and funding available for student innovators, there was a lack of information available on these. “Why isn’t there a platform where all of this is consolidated?” he thought. Then he decided to create one.

Today, Aditya’s ‘Kalam’ helps students in accessing the assistance they require to bring their ideas to fruition. As for the intent behind the name, it has a dual purpose.

“First, was the inspiration of Dr APJ Abdul Kalam, who spent his entire life advancing our knowledge of science. He served as a role model to millions of young students, including me,” he says.

The second meaning, he adds, is borrowed from the Hindi word for ‘pen’. “A pen gives us the power to tell our story and write our own destiny,” he says.

But to scale Kalam from a brainwave he had in class one day to a formal platform, he needed time. An otherwise terrible situation proved to be a blessing in disguise. Aditya met with a road accident which led to a surgery and months of rehabilitation, which, he says, provided him with time to do just that. As he narrates the incident, he smiles at destiny’s funny ways.

‘I was bedridden for three months with nothing to do but scroll the internet.’

Aditya was in the midst of his Class 12 board exams when the accident occurred. But that did not deter him from spending the next several months getting together the tools he needed to spearhead Kalam.

He says, “I wanted Kalam to be a launchpad for students from government schools. They could be those unaware of opportunities for student innovators or for those who were aware but unable to collate information.”

The team at Kalam comprises Aditya’s peers also intent on ironing out the wrinkles in the system through their platform. They lend their expertise pro bono.

“A friend of mine who is studying law is helping us with the legalities of registering the company, while another who is studying agricultural science in Agra is helping us with the finer nuances of the app,” he says. The friends believe that this is a platform for students, by students. And they don’t shy away from helping.

Kalam presently is also engaged in conducting workshops for students at various branches of Delhi’s Kendriya Vidyalaya who have ideas but lack resources. “We conducted sessions at my school where 20 kids from the neighbouring public schools were invited to a talk revolving around topics of innovation. The sessions were all about encouraging them on the various ways ideas can occur,” says Aditya, who shares that currently nine students are being helped through Kalam.

For a Class XI student of Aditya’s school, Veerjyot Singh, Kalam has been a boon. Veerjyot, who is conceptualising a real-time app that can act as an image-to-text translator and vocaliser, says he got tailored guidance from Kalam.

“Aditya provided me guidance and support on a regular basis to understand otherwise unknown avenues to develop and pitch my ideas and look for development support,” he notes.

While Aditya is happy that the platform is serving its intended purpose, he takes a broader view of things. “When it comes to applying to Ecells at IIT Mandis (entrepreneurship hubs in IIT institutes that support innovation), students often face a dilemma as to whether their ideas will be funded in the face of established startups founded by graduates with top-class degrees.”

But things are changing, he says, and hopes that Kalam will be that beacon of light for someone with an equal passion and vigour towards innovations for the betterment of people.

Edited by Padmashree Pande.

No comments:

Post a Comment