Back in 2017, Vikrant Singh and Utkarsh Singh, engineering students at Haryana’s BML Munjal University (BMU), were developing an electric racing car for a competition organised by Baja SAE (Society of Automotive Engineers) India — a non-profit engineering and scientific society dedicated to the mobility community in India.

“It’s a competition where college students design and develop vehicles and compete on automobile racing circuits like the Buddh International Circuit. It’s a very good programme for budding engineers,” recalls Utkarsh, in a conversation with The Better India.

A key component of developing an electric racing car was installing a lithium-ion (Li-ion) battery. However, finding such a battery in 2017 wasn’t easy because, back then, nobody in India was manufacturing it on a significant scale. But they eventually found a company in Ludhiana, Punjab, which was importing batteries and distributing them all over the country.

“As students, we approached that company for a battery and they even agreed to give us one for this project. But for six months they kept delaying the delivery of this battery, and eventually, we couldn’t participate in the competition. Frustrated by this outcome, Vikrant and I began discussing why these Li-ion batteries aren’t being made in India,” he recalls.

“We realised that in these batteries you have Li-ion cells and these aren’t manufactured in India for the very simple reason that you can’t find the raw materials, i.e. lithium, cobalt and nickel, required to make them. Also, at the time, electric vehicle (EV) consumption wasn’t too heavy and no one realised that this sector would take off soon. At the time, whatever OEMs (original equipment manufacturers) in India needed, they were importing those materials,” he adds.

As part of their college semester project, they decided to build Li-ion cells at a Rs 200 crore R&D laboratory set up on campus. “We ordered lithium and cobalt from China. Due to various reasons, these materials didn’t arrive on time for our project. To complete it, we bought some old Li-ion cells from the market, extracted whatever materials we could in very impure forms and then fabricated Li-ion cells (half cells) that delivered some energy,” he recalls.

“To acquire these materials in India, we needed to start recycling old Li-ion batteries. We predicted that a lot of Li-ion batteries are going to enter the country, and if we recycle them, these materials can be reused to make cells. See, you can recycle metals like lithium infinitely. That’s how the idea of BatX Energies was born. We spent the following semesters researching what’s required to recycle Li-ion batteries on a larger scale,” he adds.

After college, Vikrant and Utkarsh were very clear about learning what it takes to run a company before starting one. They worked for a little over one year in different companies with Vikrant engaged in R&D work while Utkarsh dealt with the management side of things.

Amid the pandemic in July 2020, they got back together and established BatX Energies, which is today a major Lithium-ion battery recycling startup which produces battery-grade materials.

One of their core objectives is to create a domestic circular supply chain of materials like lithium, nickel and cobalt, among others, and lessen the requirement for mining them. The company extracts rare earth metals, such as lithium, cobalt, nickel and manganese from used Li-ion cells, which are then bought by a variety of industries — including EVs, pharmaceuticals, electroplating and fertiliser. But if these used cells have some charge left, they repurpose them into batteries for off-grid solar EV chargers, inverters, or other applications.

The startup has developed an innovative procedure for recycling various batteries, employing specialised techniques and advanced hydrometallurgical processes. As a major supplier of sustainable battery solutions in India, they have even secured a patent for their Zero Waste-Zero Emission Technology and successfully recycled about 220 million batteries to date.

How to recycle and repurpose used Li-ion batteries?

The process begins with sourcing used Li-ion batteries from formal entities like EV manufacturers and ventures engaged in building stationary applications like telecom towers where these batteries are deployed, power electronics, and other electronic devices like laptops, mobile phones, etc. They also source these batteries from the informal sector as well.

“Today, about 80% of the sourcing of battery cells comes from the unorganised sector because a majority of them are extracted from mobile phones and laptops. However, our market research suggests that the organised sector will soon overtake the unorganised sector when it comes to sourcing these used batteries. Unlike laptop or phone batteries, EV batteries cannot be left in the unorganised sector. They don’t have the capacity or capability to handle them. One tonne of Li-ion battery waste is equivalent to 1 e-bus battery; 3 EV car batteries; 29 three-wheeler batteries; 40 two-wheeler batteries; or 22,000 mobile phone batteries,” explains Vikrant.

“Once sourced, you have to organise safe transportation of these old Li-ion batteries. We pay close attention to the packaging of the battery pack, discharging the battery at the collection point, ensuring no wiring is kept open or exposed and all the charging and discharging slots are well-capped. We have made sure to follow these basic safety measures,” claims Utkarsh.

Although the startup is based out of Gurugram, Haryana, its main recycling facility lies in Sikandrabad near Bulandshahr, Uttar Pradesh. There are two things that happen here.

Once these used batteries reach the BatX facility, they will break them down into different modules and cells, run them through a series of tests, and conduct an analysis of the cell performance. If some of these cells still have some charge left and can perform for another life in a different application, the BatX team repurposes them for second-life applications.

“For example, you have a cell, which can be reused for a torch or in a small electronic device. If it’s a four-wheeler battery, we can reuse its cells in an energy storage application. We closely gauge how much charge remains in this battery. Using our IoT devices, we need to be very sure when the battery is coming to the end of its second life. It’s a very important part of the process. If there’s a malfunction, we repair it. Once those cells have been exhausted, however, we take them for recycling. If these cells cannot be reused as per our first assessment, we take them straight away for recycling. That’s how you create a circular economy,” he adds.

From second-life EV batteries, for example, BatX Energies has built 100% off-grid solar EV chargers for EV OEMs like MG Motor. They have even developed home inverters employing second-life EV batteries at the same cost as a lead-acid inverter, which is hazardous.

“We have developed a small unit which can run for five years. We are going to deploy these inverters soon in rural Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh. Once these second-life batteries come to the end of their lives, we will take them back and recycle them,” notes Utkarsh.

Once the batteries are deemed not fit for second-life applications, they are dismantled, discharged, and crushed into powder at their facility in Sikandrabad, Uttar Pradesh. They call this crushed powder ‘black mass’, which is then transported to their main chemical recycling facility, and here, they extract materials like lithium, cobalt, nickel, etc.

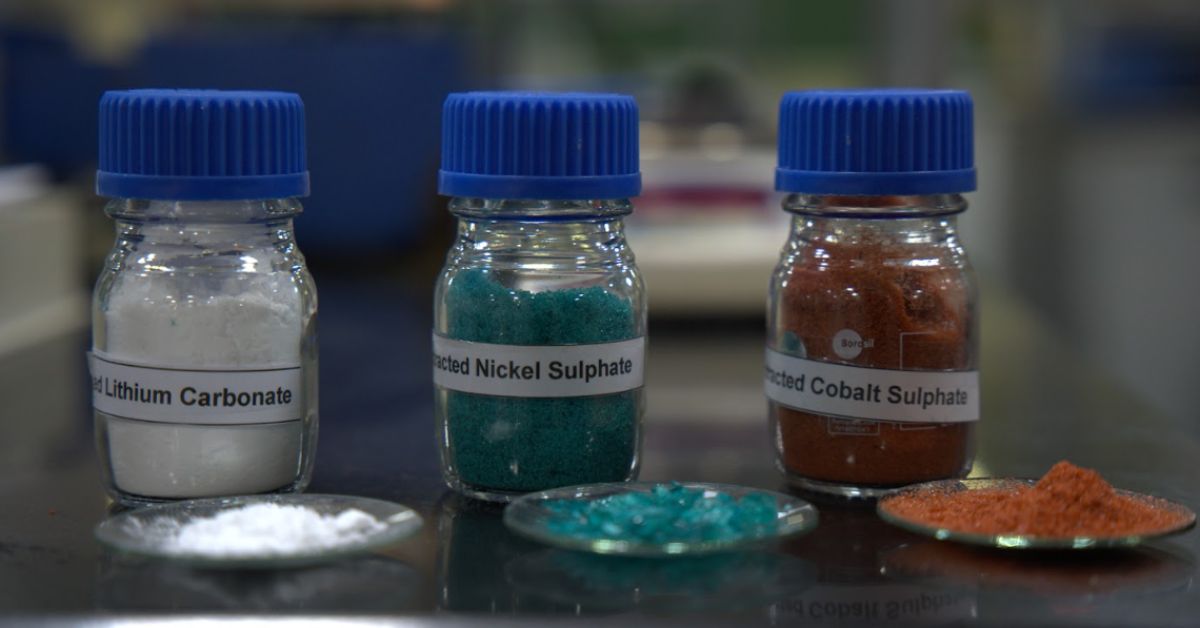

“From the black mass, all battery grade material including graphite is removed, and then impurities like aluminium, copper and cake. After this, we extract lithium, nickel and cobalt. Once we extract these materials, we sell them to material refiners who use them to make new Li-ion cells. But materials like lithium are also used in the pharmaceutical industry to make anti-depression medication, etc. Cobalt, meanwhile, is used in the ceramic and pain industry while Nickel is employed in electroplating and the fertiliser industry as well. We only produce high-grade material (99.6% purity),” claims Utkarsh.

Vikrant goes on to claim that the process they have developed to repurpose or recycle these old batteries is chemistry-agnostic — whether they are lithium iron phosphate (LFP) batteries, lithium nickel manganese cobalt (NMC) batteries, Li-ion batteries, or lead acid batteries.

“It took us five years to design and develop this process we have established. We currently have a patent on our ‘Waste to Zero Emission Technology’. The patent is on their apparatus, methods and process. Since we initially didn’t have enough funds, we developed the recycling plant ourselves. We have not imported any of the machinery in our production plant,” claims Vikrant.

In the near future, however, BatX will look to alter their operations based on a hub and spoke model. Although their main centre of operations lies in Sikandrabad, UP (Hub), they are planning to set up different facilities (spokes) in places like Hosur in Karnataka, Siliguri in West Bengal, and Gujarat. Why are they adopting this new operating model?

“Let’s say, we collect old Li-ion batteries from Maharashtra but want to transport them to our hub in UP. Despite all the safety measures we take, there is some risk involved in transporting them. That’s why we are planning to create facilities (spokes) in states like Gujarat (and West Bengal, Karnataka) so that we can transport our old batteries from Maharashtra there,” he says.

Funding and looking ahead

In late December 2023, BatX Energies raised USD 5 million in pre-Series A funding. The round was led by investors, such as Zephyr Peacock, but also saw participation from investment platforms like Lets Venture and existing investors like JITO Angel Network, and family offices of Mankind Pharma, Excel Industries, and BluSmart, among others.

In the press release they issued, Pankaj Raina, managing director of Zephyr Peacock said, “The company is poised to become a crucial stakeholder in the battery supply chain in India, as recyclers will be a significant source of critical materials for Li-ion battery manufacturing. We are excited to partner with them on this journey.”

Speaking to The Better India, however, Utkarsh says, “In five years, we are going to recycle approximately 25% to 30% of deployed Li-ion batteries in India. We will supply the material back to industry players who can produce 95% of the battery bank back from recycled materials.”

(Edited by Pranita Bhat; Images courtesy BatX Energies)

No comments:

Post a Comment