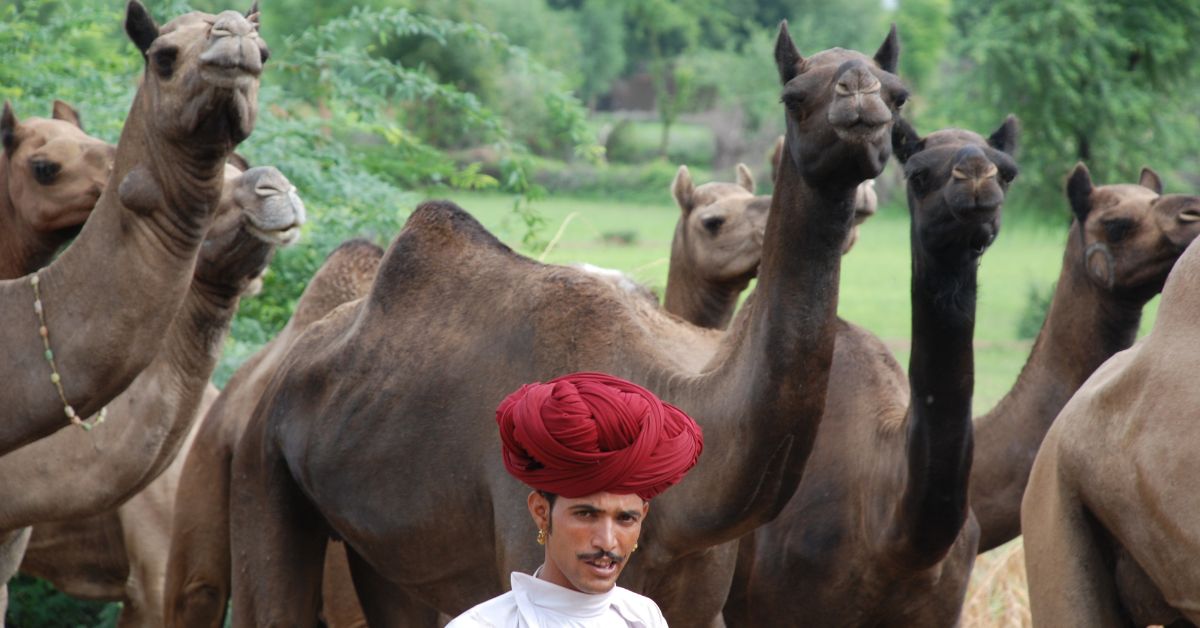

Welcome to Sadri town in the Pali district of Rajasthan. Sightings of men dressed in white angrakhas (a tunic-like dress) complete with colourful turbans (most often crimson) that shelter their heads from the blazing heat will dot your visit.

These are members of the Raika community.

The pastoral community has been herding camels for centuries. What distinguishes them, aside from their attire, is that they never travel solo. Within metres, you’ll spot their closest friends — distinguished by a hump, long lashes, bushy eyebrows, and thick pursed lips.

Stately creatures, the camels seem content. The darkening sky and the spring in their step suggest a long day of grazing on thistles (the remnants in the fields following harvest) is now complete. Having watched and closely engaged with the camels for over three decades now, Germany’s Dr Ilse Köhler-Rollefson has a good measure of an informed opinion on camel behaviour.

She points out that thistles while forming a bulk of the camel’s nutrition, aren’t the only plants they feed on. And this is backed by solid reasoning.

The co-founder of Camel Charisma goes on, “According to traditional knowledge, camels eat 36 different plants.” The green diversity boosts milk production and quality, she points out. Considering that dairy is the prime occupation of the Raika community, milk quality is vital.

It is of essence to note that only in the recent past has dairy emerged as a focus industry for the community. If the humped creatures could speak, they would tell of how their ancestors enjoyed a different set of privileges.

Come November, their predecessors were decked in finery and embroidered cloths as they made their way to the Pushkar Mela — an annual multi-day livestock fair dating back to the 19th century. Here, they were traded as modes of transport in exchange for handsome sums of money to the tune of lakhs.

Reminiscing about those times, Karan Ram, one of the members of the Raika community, who often accompanied his family to these events, shares, “We [the Raika community] would earn a lot through the mela (town fair). In fact, we used to make more money in that one month than we would all year,” he smiles.

But in 2014, things changed.

The Government took cognisance of the camel’s declining population in the state of Rajasthan — a 54 percent plummet in numbers between the years 1998 and 2012 (according to an article in Down To Earth). In response to this, the camel was declared the state animal of Rajasthan.

This was followed by the Rajasthan Camel (Prohibition of Slaughter and Regulation of Temporary Migration or Export) Act (2015) which banned the slaughter, trading, and unauthorised transportation of camels in the state.

Despite being good news for the camels, it impaired the source of livelihood of the Raika community. In the years that followed, the Pushkar Mela lay deserted.

Karan was one among many in his community who spent years navigating the perils of the effects of the order. Worry clouded his youth. But today, as he speaks to The Better India, there is no trace of doubt. Karan boasts that he has 40 camels and is looking to expand his herd.

So, what changed in this last decade to make Karan a proud pastoral? He responds, “I came to know about Camel Charisma.”

The social enterprise co-founded by Dr Ilse Köhler-Rollefson and Hanwant Singh Rathore, aims to develop, promote and market environment-friendly products sourced from the camel. Rathore is also the founder of Lokhit Pashu Palak Sansthan (LPPS), which works to conserve camels in the state.

A tale of two cities

I was intrigued by how a PhD scholar in veterinary medicine from Germany forged a friendship with a Rajasthani local, and how in no time, the two dived into entrepreneurial waters. I urge Dr Ilse to narrate the story. And she takes me back to 1991.

In India for a fellowship, Dr Ilse couldn’t refrain from meeting with the Raika community. “India had the third-largest population of camels at the time,” she explains her decision. And so, she set out to venture into the Pali district of Rajasthan.

Her taxi driver — a gentleman named Hanwant Singh Rathore — seemed particularly chatty. As Dr Ilse discovered, not only was Rathore well versed with the region’s (convoluted) history with camels, but also fluent in the local dialect. He would make for a great company, she thought.

Soon, a taxi conversation blossomed into a friendship, and before the duo knew it, they were taking a leap of faith — Dr Ilse decided to extend her stay in India (it’s been 33 years) while Rathore decided to quit his chauffeur business.

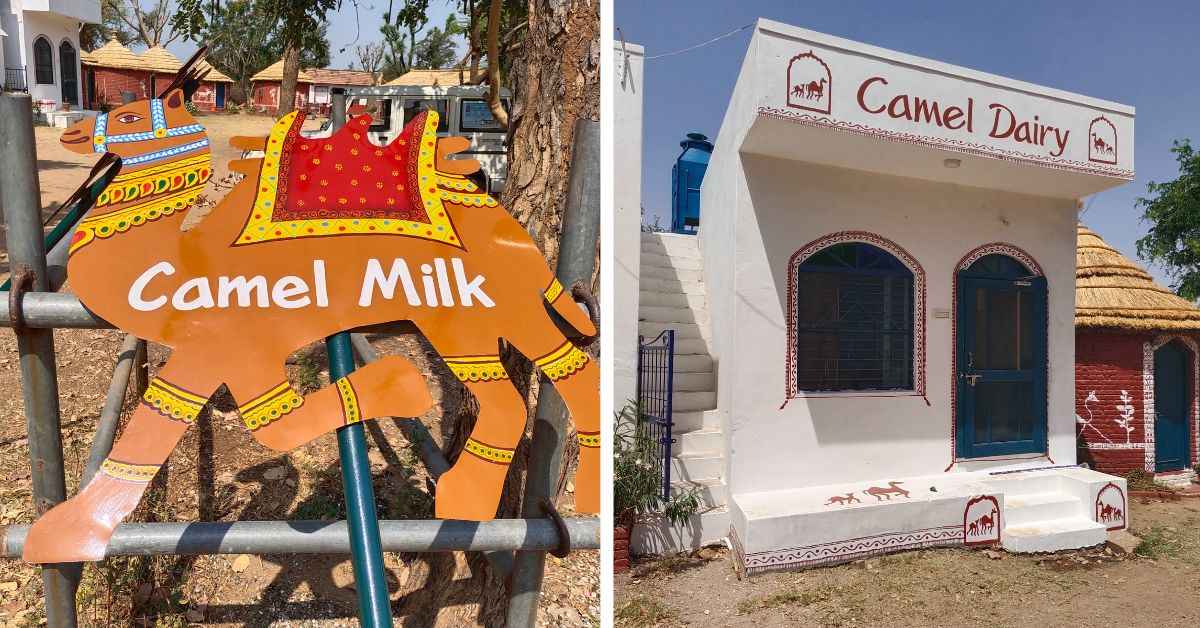

Since the chance meeting, the duo have been charting a map for the preservation of camel numbers, stoking relations with the Raika community to gain their trust, and championing change through new dairy models. In fact, Camel Charisma is credited with setting up Rajasthan’s first dedicated camel dairy ‘Kumbalgarh’ Camel Dairy in 2019.

The allure of camel milk

In 2020, during the COVID-induced lockdown, the Times of India covered a story about a woman who took to ‘X’ (formerly known as Twitter) to appeal for help in sourcing camel milk from Rajasthan. The milk, as she explained, was for her 3.5-year-old child who had autism and survived on a diet of camel milk and pulses.

This story sheds light on a question: Is camel milk effective for autism?

Research papers agree, adding that it is not just autism that the milk helps with but a host of medical conditions. According to a 2021 paper published in the National Library of Medicine, camel milk could play an important role in decreasing oxidative stress by altering antioxidant enzymes. The paper postulated that this in turn could improve autistic behaviour.

Another research paper published that same year explored the nutritional and medicinal benefits of camel’s milk. It revealed that the milk’s abundance in bioactive peptides, lactoferrin, zinc, and mono and polyunsaturated fatty acids could help in conditions like tuberculosis, asthma, gastrointestinal diseases, and jaundice.

Meanwhile, a 2011 study by R P Agrawal, head of the Diabetes Care and Research Centre at S P Medical College, Bikaner, found that by drinking camel milk for a prolonged period of time, patients suffering from Type 1 diabetes can reduce their insulin dependence by 60 to 70 percent.

For years, camel milk has been touted as ‘good’ for stunted children, nursing women, and anaemic women; Dr Ilse seconds these claims. The more she furthered her research into the topics, the more she was convinced that camel milk could be a boon for public health. But when she relayed her findings to the Raika community, they wouldn’t have it.

Breaking down the taboo that has bordered the sale of camel milk, Rathore makes us privy to a conversation he had with one of the members. “He [the herdsman] said it was almost like being asked to sell their children,” Rathore shares. It took years of meetings, and talks with the community priests and elders to encourage them to heed the advice to turn to camel for dairy.

Just when the community was beginning to trust them, a 1999 order by the Rajasthan High Court noted that camel milk wasn’t good for human consumption. Led by Rathore, a team appealed to the Supreme Court and the order was soon overruled. But Rathore did not stop there. He kept persisting until in 2016, camel milk was recognised as a food product by the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI).

Empowering a community

In 2019 came an inflection point when Dr Ilse and Rathore’s work transcended advocacy and veered into empowerment. This had big implications for the Raika community.

Take Karan for instance. Now earning a stable income of Rs 25,000 a month through the sale of camel milk, he is thrilled. “I remember a time when people would call camel’s milk useless. Now it has become popular because of Hanwant ji,” he shares.

Karan is among the dozen dairy farmers being empowered by Camel Charisma. What is unique about their model is that it is cruelty-free and borrows from traditional knowledge of the Raika community.

“We don’t follow the industrial model of camel milk production where camels are stall-fed to maximise the production,” Dr Ilse explains. “The community believes that camels need to move to be happy and healthy; they need to have dietary choices of trees from which they wish to nibble. In contrast to commercial dairy enterprises, we don’t separate the mother from the calves.”

While Camel Charisma is a force to reckon with today, the journey hasn’t been without its challenges. “I remember the first order we had for camel milk,” Dr Ilse smiles. “We were wondering how to package and transport it and came up with the concept of 200 ml bottles. We froze the milk and sent it out frozen. It took some experimentation to get the technique right.”

Despite having perfected the technique, she notes that the remoteness of the location has hindered sales. But things are improving. Camel Charisma has managed to become a home name and clocks monthly sales of over 3,000 litres of camel milk across India.

The duo credits the success to the quality of the milk — pure and natural. In fact, they explain that the fat and water content are not standardised and fluctuate according to the season: during the summer its water content is higher, while in winter fat content increases.

Every herder needs to be registered and have a health certificate. The latter is provided by the Department of Animal Husbandry of the Government of Rajasthan.

While the dairy is one arm of Camel Charisma, a cheese-making unit churns out delicious feta that finds fans in guests at the Lake Palace, Udaipur. The wool-making unit turns wool into fibres that are spun into dhurries (rugs). Meanwhile, the paper-making unit produces paper from the dung of Kumbhalgarh camels.

These units work in tandem to manufacture products, that, once go out into the world, empower the Raika community. And standing proud at their creation are Dr Ilse and Rathore.

As we reach the end of the tale, another day is winding down in Rajasthan. Jhimpri, Raathi, and Dhooli are making their way home led by their master and friend — Karan. With time, their [the camels’] lifestyles have changed. Now, they don’t head to melas to be traded but instead to safe spaces, where they are cared for.

As one among the herd nuzzles Karan, one thing is clear — the bond between the camels and the Raikas is timeless.

Edited by Pranita Bhat

No comments:

Post a Comment