Growing up in Choglamsar, a dusty urban settlement on the outskirts of Leh town, Dr Lobzang Chorol witnessed firsthand the critical role water plays in this cold desert. Speaking to The Better India, Dr Chorol recalls two specific incidents that left an indelible impression on her.

“During my childhood, I vividly remember a summer when the PHE (Public Health and Engineering) tanker failed to arrive, leaving us without a water supply. We had to walk long distances to fetch water for our basic needs. I saw the worry on my parent’s faces and the strain it put on our entire community. This crisis opened my eyes to the fragility of our water resources and the urgent need for better management and understanding,” she recalls.

The second incident Dr Chorol recalls is from her undergraduate days when she visited her ancestral village called Skumpata (Lingshet) in Ladakh, which is about 80 km from Leh town.

“I was struck by the ingenious traditional water management systems our ancestors had developed — the intricate network of channels and storage ponds that had sustained life in this harsh landscape for centuries. However, I also noticed how these systems were under threat from changing climate patterns and modernisation. It made me realise the importance of bridging traditional knowledge with modern scientific approaches,” she recalls.

It’s this fascination and concern that motivated her to better understand the cold desert’s water systems to pursue her PhD at IIT-ISM (Indian School of Mines), Dhanbad. Under the mentorship of Professor Sunil Kumar Gupta, a leading expert in the field, she closely studied the groundwater systems in Leh town. Spanning six years and eight months, her research finally culminated in the completion of her thesis earlier this year. (You can find it here.)

There were times when the challenges seemed overwhelming — from people unwilling to give their borewell water samples to collecting secondary baseline data and the emotional weight of seeing the deterioration of Leh’s water resources firsthand.

“But every time I felt discouraged, I remembered the faces of my family and community back in Ladakh, depending on this precious resource. It wasn’t just academic research; it was about the lives and futures of real people. It wasn’t just about earning a degree; it was about securing a sustainable future for Ladakh,” she says.

Leh’s invisible network of underground aquifers

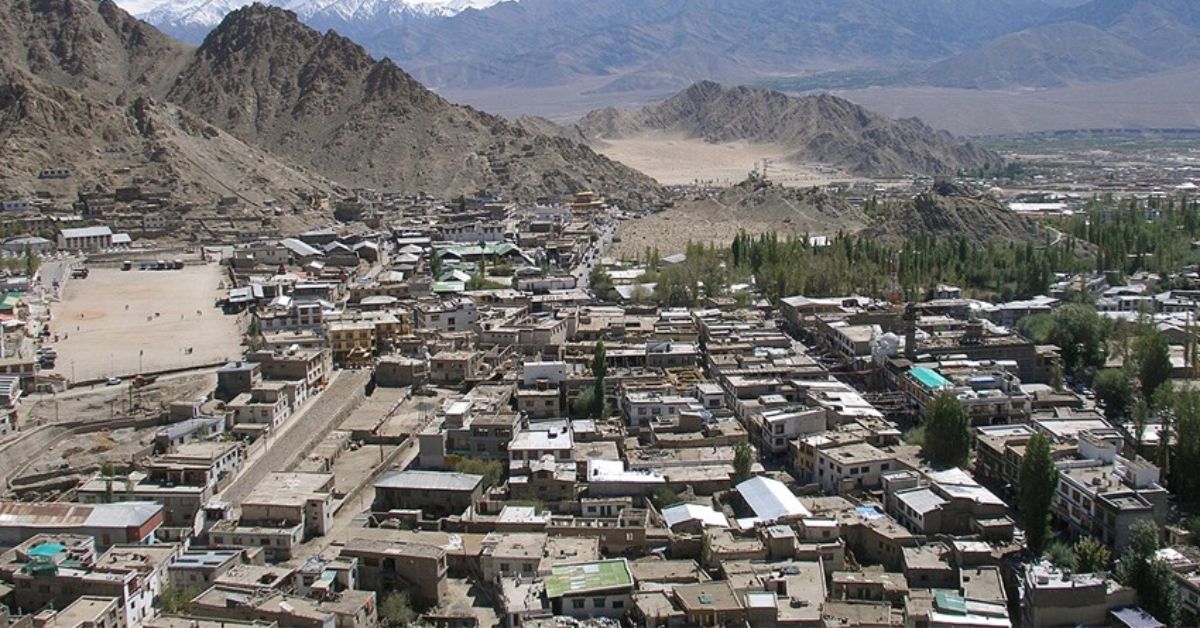

Leh is a town nestled in the rain shadow area of the mighty Himalayas, receiving barely 100 mm of annual rainfall. Life in this high-altitude desert thrives against all odds, thanks to an invisible network of underground aquifers.

“These aquifers are essentially natural underground reservoirs formed in the porous layers of rock and sediment beneath Leh. They are recharged primarily by snowmelt from surrounding mountains, glacial melt from nearby glaciers, limited annual rainfall, and infiltration from rivers and streams. This recharge process is heavily influenced by seasonal patterns, with most occurring during the warmer months when snow and glaciers melt,” explains Dr Chorol.

These aquifers act as a natural storage and filtration system, holding water that percolates through the ground and releasing it slowly over time. Additionally, the groundwater maintains a relatively stable temperature, which can be beneficial for both ecosystems and human use.

“The way these aquifers support Leh’s thriving is multifaceted. They sustain natural vegetation crucial for the local ecosystem and enable agriculture in an otherwise arid environment. For human use, they feed springs used for drinking water, supply water for wells, and support traditional water management systems like zings (ponds) and yura (channels),” she notes.

“The stored water in aquifers helps Leh withstand periods of low precipitation, providing resilience against drought. This consistent water supply allows for urban development and supports the growing tourism industry,” she adds.

Understanding and properly managing this invisible network of aquifers is crucial for Leh’s sustainable future, especially in the face of climate change and increasing water demands.

But this crucial lifeline is under severe threat.

‘Slowly poisoning the very veins that sustain us’

With rising tourist footfall, unplanned development and poor water management practices, Dr Chorol’s nearly seven-year research into Leh’s groundwater has come up with some troubling findings.

Decline in water quality: “Over the past six years, we’ve observed a significant decrease in water quality. For instance, Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) levels have increased by about 30% in some areas, from an average of 300 mg/L to over 400 mg/L. This rapid increase is alarming. To give you an idea of how serious the problem is, let me share some of our key findings,” she notes.

“For drinking water, we found that 3.57% of our samples were of extremely poor quality, and another 3.57% were poor. What’s particularly concerning is that 92.86% were only of average quality, and we didn’t find any samples in the good or excellent categories,” she explains.

“Nitrate levels have risen by up to 50% in certain wells, approaching the World Health Organization (WHO) limit of 50 mg/L in some cases. We’ve also detected increasing concentrations of heavy metals like chromium and cadmium with some samples showing levels two to three times higher than what we observed six years ago. For irrigation water, the situation is equally worrying. We found that 3.57% of samples were very poor, 42.86% were poor, and 53.57% were average. This indicates a widespread issue with water quality,” she adds.

Change in groundwater chemistry: The chemical composition of Leh’s groundwater has altered noticeably. “We’re seeing increased levels of ions like chloride, sulphate, and sodium, which are typically associated with human activities. For example, chloride concentrations have risen by about 40% in some wells over the six years,” she explains.

“This change suggests contamination from sources like improper sewage disposal and the concentration of major cations has increased, following the order of calcium, magnesium, sodium, and potassium. We’re seeing higher levels of sodium, potassium, fluoride, and nitrates, which we believe are linked to the increased use of agrochemicals in agriculture,” she adds.

What’s particularly concerning is the elevated levels of heavy metals we’re detecting. Iron, manganese, chromium, nickel, cadmium, and copper are all present at levels exceeding permissible limits in many of the samples studied by Dr Chorol.

“We’re seeing contamination from various sources — sewage leaking from poorly maintained septic systems, agricultural runoff from fertilisers, waste from increased tourism, and lack of proper wastewater treatment facilities. Each of these sources might seem small on its own but together, they’re having a significant impact on our water quality. It’s a complex issue, but understanding it is the first step towards addressing it,” she notes.

Health risks: “Firstly, we found that certain heavy metals, such as chromium, cadmium, and nickel, present in the groundwater have the potential to increase the risk of cancer. This risk is particularly concerning for children, who are more vulnerable to the effects of these contaminants due to their developing bodies and higher water intake relative to their body weight. In addition to the carcinogenic risk, we also identified non-carcinogenic health risks posed by chromium in the groundwater,” explains Dr Chorol.

Apart from heavy metals, her study also investigated the health risks associated with fluoride and nitrate exposure in the groundwater.

“The hazard quotient analysis revealed that the oral pathway, i.e. drinking contaminated water, was the primary route of exposure for all age groups. Fluoride and nitrate were found to be the major contributors to these health risks with children and infants being the most vulnerable to their effects. Fluoride, when consumed in excess, can lead to dental and skeletal fluorosis, which can cause discolouration and damage to the teeth and bones. Nitrate, on the other hand, can interfere with the blood’s ability to carry oxygen, leading to a condition called methemoglobinemia, which is especially dangerous for infants,” she notes.

Impact of climate change

From 27 July to 30 July 2024, around 12 flights couldn’t touch down at Leh’s Kushok Bakula Rinpoche Airport while many more were cancelled. The maximum operating temperature of Leh airport is 32°C but on 28 July, the Leh division recorded 33.5°C as per the Metrology Centre of Ladakh. Similarly, the temperature recorded in the Kargil division was 37.5°C.

Ladakh was burning this summer because of a huge deficit in rainfall. It received 3 mm of rainfall till the start of August as against the normal of 15 mm.

This lack of precipitation and intense heat wave has dried out the soil, causing crops to wither and trees to require more water. Meanwhile, groundwater exploitation by drilling more borewells has further accelerated the decline in groundwater levels and reserves.

As we all know, Leh is located in a high-altitude desert region, where the primary source of water for our aquifers is the melting of glaciers and snowpack in the surrounding mountains. However, as recent events indicate, climate change is causing significant alterations to this delicate balance, leading to severe consequences for our groundwater resources.

One of the most prominent effects of climate change is the increase in global temperatures. The rapid melting of glaciers leads to a surge in water flow during the summer months, but it also means that there is less water stored in the form of ice to sustain the flow during dry seasons.

“Moreover, climate change is also altering precipitation patterns in Leh. We are experiencing more frequent and intense extreme weather events, such as heavy rainfall and flash floods. While these events do contribute to the recharge of our aquifers to some extent, they also lead to increased surface runoff and soil erosion. As a result, a significant portion of the rainwater is lost before it can percolate into the ground and replenish our aquifers,” says Dr Chorol.

“Another factor to consider is the changing vegetation cover in the region. As temperatures rise and precipitation patterns change, we are observing shifts in the local ecosystem. Some native plant species like seabuckthorn, willow and poplar that play a crucial role in retaining moisture and promoting groundwater recharge are struggling to adapt to these new conditions. The loss of these species can further exacerbate the problem of reduced aquifer recharge,” she adds.

Broken sewage system

The current state of Leh’s sewage system is a significant concern when it comes to the quality of its groundwater. Unfortunately, the town lacks a comprehensive and efficient sewage treatment system, which has led to the deterioration of our groundwater resources over time.

“At present, most of the households and establishments in Leh rely on individual septic tanks or dry soak pits for wastewater disposal. While these systems are designed to treat wastewater to some extent, they are often poorly maintained, overloaded, or improperly constructed. As a result, untreated or partially treated sewage can seep into the ground, contaminating our aquifers with harmful pollutants such as nitrates, bacteria, and viruses,” notes Dr Chorol.

Moreover, the rapid growth of tourism and urbanisation in Leh has put additional strain on the existing sewage infrastructure. The increased volume of wastewater generated by hotels, restaurants, and other commercial establishments often exceeds the capacity of their septic systems, leading to the overflow of untreated sewage into the environment.

“Our study has revealed elevated levels of nitrates, faecal coliform bacteria, and other contaminants in many groundwater samples, indicating the impact of sewage infiltration. These contaminants pose serious health risks, especially to children and the elderly,” she says.

“While the local administration has taken some steps to address the issue, such as promoting the construction of improved septic tanks and encouraging the use of eco-friendly toilets, these measures have been insufficient to keep pace with the growing challenges,” she adds.

Furthermore, the increased demand for water due to population growth and tourism puts additional pressure on our groundwater resources. “As more water is extracted from the aquifers, the natural recharge process is unable to keep pace, leading to a decline in groundwater levels and potential depletion of our aquifers in the long run,” she adds.

Groundwater extraction in Leh

According to a recent study published in April 2024 in the Journal of Water and Climate Change led by Dr Farooq Ahmad Dar — assistant professor at the Department of Geography and Disaster Management, University of Kashmir — groundwater extraction and decline in Leh has increased significantly in recent years. Here are two key data points from the study:

1. Well drilling:

- In 1997, there were only 10 drilled wells in Leh.

- By 2020, the total number of wells had grown to 2,659.

- This represents an increase of about 115 new wells per year.

2. Groundwater extraction:

- Groundwater extraction increased by approximately 26% from 2009 to 2020.

- About seven million cubic metres of water are drawn annually from wells.

Speaking to The Better India, Dr Dar says, “These figures should raise alarm bells in the region. In simple language, these figures highlight the current scenario of groundwater pumping. When more people will shift to groundwater and drill their own wells, there will be no check on the reserves. Groundwater is a State Subject and that means it is the responsibility of the local administration to have legal checks on its use and misuse.”

“In this scenario, when more wells will be drilled, which we estimated at a rate of 115 wells per year (these figures are based on limited data, the rate could be even higher), the reserves will be depleted very rapidly and the drilled wells will also fail/dry out. This will have severe consequences on irrigation, tourism, industries, agriculture and people’s lives. So, the Government must intervene urgently to address this problem,” he adds.

3. Population growth:

- The population of the Ladakh region grew from 29,730 in 1901 to 1,52,175 in 2020.

- This represents an annual growth rate of 15%.

4. Urbanisation:

- The built-up area increased by 20% from 1969 to 2017.

- In the last 10 years, the built-up area around major towns increased by about 75%.

5. Glacier shrinkage:

- Glaciers in the region have shrunk by 40% in area and 25% in volume since around 1650 AD.

- This reduces the glacier melt that replenishes groundwater.

While his study doesn’t provide specific measurements of groundwater level decline, it states that these factors have led to an imbalance between water demand and supply, decline of shallow resources, reduction of natural discharge, drying of springs, and decline in water levels.

“Without immediate intervention, the quality and quantity of Leh’s groundwater will continue to decline rapidly over the next 20–30 years. It’s a countdown we cannot ignore,” says Dr Chorol.

Solutions

There are many actionable solutions that the local government, administration, business owners, and residents can take to address the growing concern surrounding groundwater.

1) Stricter regulations for groundwater extraction: Mandatory permits for groundwater extraction; metering of groundwater usage; pricing of groundwater; strict zoning regulations; establish clear guidelines on the minimum distance between borewells and septic tanks; hefty fines for businesses found dumping waste in water bodies; and regular mapping of groundwater resources.

2) Upgrading and improving Leh’s sewage management system: Establish a decentralised sewage treatment plan with small-scale treatment systems; install advanced septic systems and dry toilets and composting systems; upgrade existing STPs and construct new ones in areas not covered by sewage network; invest in advanced water treatment technologies; and establishing a regular water quality monitoring programme.

3) Tourism industry stepping up to the plate: Encourage hotels, guesthouses, and restaurants to install water-efficient fixtures; promote the use of greywater recycling systems; install rainwater harvesting systems; charge water conservation fees for tourists with proceeds going to local water management projects; and mandatory water audits for all hotels and guesthouses.

4) Leveraging traditional water management systems: Promote traditional rotational water distribution system (bandabas); implement indigenous engineering techniques, such as Ladakh’s intricate canal systems (ma-yur, yu-ra); develop and implement context-appropriate irrigation systems taking into account modernisation and climate change; and introduce traditional ceremonies related to water management to get buy-in for the conservation effort.

(In Part 2, we will further discuss actionable solutions and recommendations by experts to mitigate the extraction of Leh’s groundwater and improve its quality.)

(Edited by Pranita Bhat; Images courtesy Dr Lobzang Chorol, Shutterstock, PixaHive and Reach Ladakh)

No comments:

Post a Comment