It’s well known that pangolins are the most trafficked mammals in the world, largely due to their high demand in traditional Chinese medicine. Unfortunately, their numbers are rapidly declining, yet they are such elusive creatures that we don’t even have an accurate estimate of their population in the wild.

Well, in the hills of Manipur, the impact of the loss is finally evident. “Without pangolins, our crops are dying,” exclaims Thomas, the Church catechist of Razai Khullen village. Pangolins and crops — what could be the connection? “Our houses are falling and our forests are decaying,” he adds, fuelling my curiosity further.

Over the next week, I travel with a team of conservationists from the Wildlife Trust of India (WTI) to understand the implications and what is being done to ensure the survival of the pangolins in the hills of Manipur.

Joining tribes for the sake of pangolins

I am in Chingjaro — one of the last villages in the Indian state of Manipur — just a few kilometres from the borders of Myanmar. In between, are lush mountains connected by a narrow, remote and dodgy road. Long before reaching the border, you can already feel a distinct change in the surroundings. This place is nothing like Imphal, the state capital where I started my journey a few days earlier.

Manipur has been making headlines in recent years due to community clashes between the Meitei, Naga and Kuki tribes of the state. Hundreds of people have lost their lives, several homes have been burnt and thousands have been left homeless. The people have taken up arms to defend their territories and the tension is apparent everywhere.

Yet, amidst the chaos, there is also a deep sense of unity and responsibility. While accompanying the team from the Wildlife Trust of India, I realised they have been working tirelessly amidst the turmoil to secure better protection for the world’s most trafficked animal — the pangolin.

As we drive from Imphal to Ukhrul, Chingrisoror Rumthao, the field officer with WTI’s Countering Pangolin Trafficking Project, recounts his experiences. “It might seem completely out of place to talk about saving wildlife, when hundreds of people are getting murdered, but truth be told, there is still hope,” exclaims Chingrisoror.

This is also a community that has sustained on wild meat for generations. Over the past year, Chingrisoror has been travelling from village to village, talking about the importance of the pangolin and how the species is fast becoming rare in these hills.

As a Tangkhul Naga himself, he understands the importance of hunting as part of both tradition and sustenance. “People in the remote hills have little access to modern amenities and livelihoods. Medical facilities are limited and so are the schools. There are still villages where electricity hasn’t yet arrived,” Chingrisoror states.

Without jobs and access to modern resources, the youth of the community have little to do. Hunting, a life skill that has been passed on through generations, seems to be both productive and important. “People in villages like Chingjaro don’t have enough money to buy poultry. To be able to feed your family, you need to go out and hunt,” adds Chingrisoror.

Pitching wildlife conservation had to have a different approach in these parts.

Locally known as the Saaham, the pangolin has been a part of the diet for most. Its scales are believed to have medicinal properties and this alleged property has kept the demand for the animal high across the borders.

With Manipur sharing an international border with Myanmar, several illegal trades have flourished in this region. Alongside arms and drugs, border towns like Moreh have been the hub for illegal wildlife smuggling. Moreh on the Indian side and Namphalong on the Myanmar side are inhabited by the same communities. This makes international transfers easier and shipments of pangolins and pangolin scales have been quite common.

Thomas recalls, “Even a decade ago, locals would load trucks full of pangolins, which earned them good money.” Other villagers, who wished to remain anonymous, explained that the business has worked to their disadvantage. The locals would sell pangolin scales at rates that would increase tenfold once they crossed international borders. Over the years, the pangolin has become rare in the hills, reasoned by uninhibited hunting.

An animal that could be seen almost every day in the fields is now an opportunistic sight.

“A major part of the trade is being facilitated at the borders where refugee camps are in place,” exclaims Khavangsing Mahakwo (name changed). “While locals do occasionally bring (or used to bring) home a pangolin for self-consumption, there has to be more awareness in these camps, if the project was to succeed,” Khavangsing adds.

Understandably, for people trying to grab onto any resource they could find, pangolins seem like a profitable trade-off. The sacrifice of wildlife for a few extra meals for the family seems justifiable, even if the law says otherwise. There is a pressing need for awareness, alternatives, and effective enforcement.

The mountains dry up without the pangolins

There have been other adversities attached to the lack of pangolins in the hills. S A Ramnganing, former President of the Tangkhul Naga Awunga Long (TNAL) — the apex body that oversees the community management and its governing laws — says, “The decline in pangolin numbers has made the hills drier. It is an animal that burrows and opens up underground tunnels that help soak up rainwater and keep the ground moist, all around the year. Without them, the earth dries up, and rainwater trickles down to the valley, unhindered. This has taken a toll on whatever food crops we try to grow.”

An interesting insight!

The decline in pangolin numbers has also been identified as the reason for the increase in termite population in the forest and the village. “There are just more termites eating away our wooden houses and trees now,” adds Ramnganing. He was among the first people to take up the cause, as head of the community, and recently, the TNAL took a historic step by signing a written resolution that bans the hunting of pangolins.

With 230 villages, including Chingjaro, falling under the apex body, they are all automatic signatories to the resolution now.

The message by Chingrisoror and WTI’s team has already spread far and wide. The pangolin (both the Chinese and Indian species) is protected under India’s Schedule I of the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972. However, The TNAL resolution is the binding law in this part of the country. Kashung Tennyson, current president of the TNAL, says, “Until we take strict measures in the protection of the species, we might lose it forever. A resolution passed by the TNAL is binding for all members of the community. This will successfully disrupt the existing illegal trade network and trafficking routes.”

The first step towards the protection of the species would be to ban commercial hunting. The supply has to stop if we are to save pangolins in India. WTI’s project, supported by the WCN Pangolin Crisis Fund, aims to raise awareness alongside stricter enforcement of the existing laws.

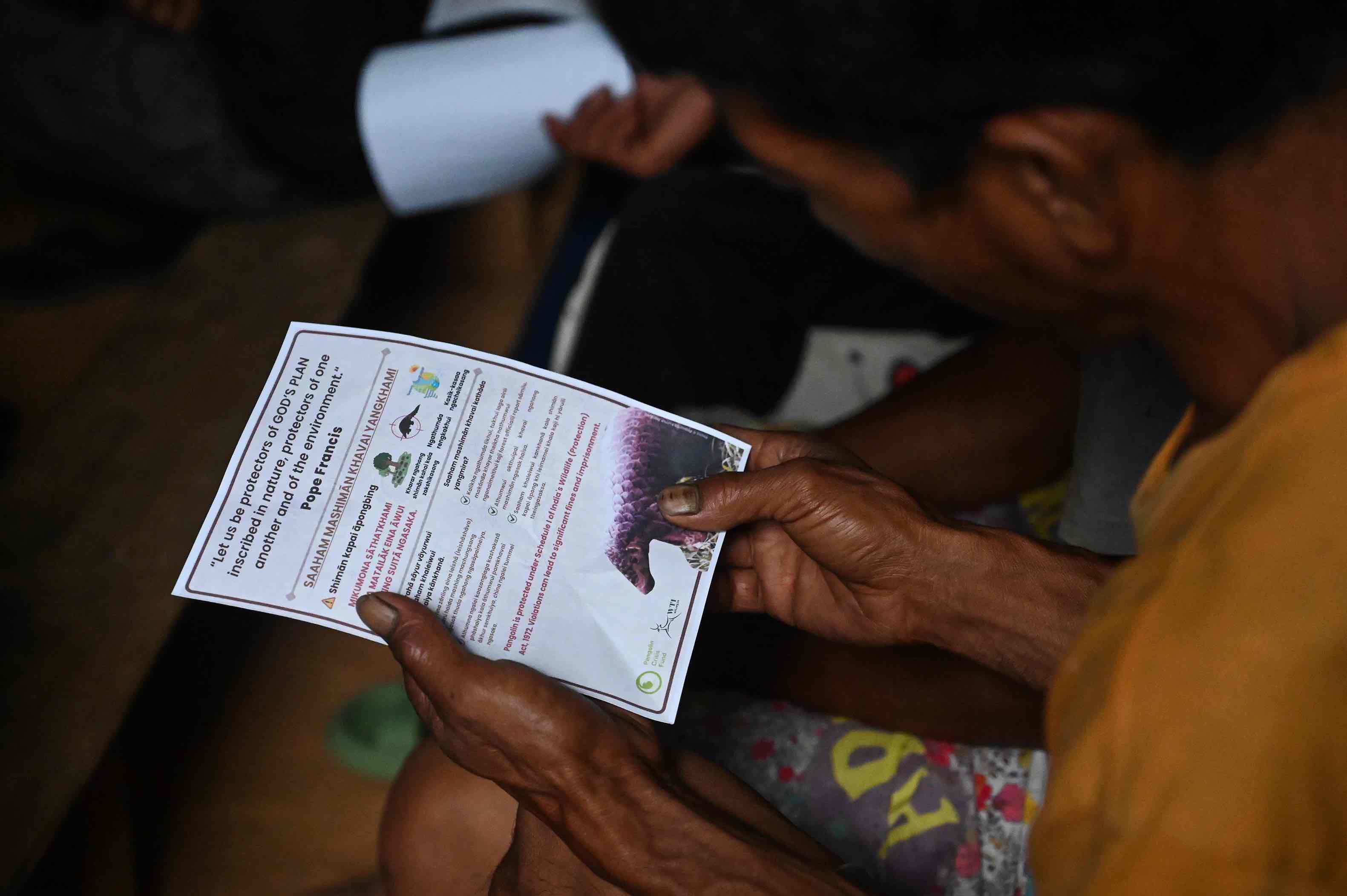

To add support to the cause, WTI has also reached out to the local churches, both the Baptist and Catholic. At the Sunday gatherings, the pastor reads out from a pamphlet that has been circulated among the audience — “Saaham madhiman khavai yangkhami” translating to “Protect the Pangolin”.

The pamphlet starts with quotes like “Let us be protectors of GOD’s PLAN inscribed in nature, protectors of one another and of the environment” from Pope Francis and “The LORD God then took the man and settled him in the garden of Eden, to cultivate and care for it” from Genesis 2.15. The message seems to have been well received by everyone in the community.

Illegal wildlife trafficking in Manipur

Manipur, which boasts a considerable population of the Chinese pangolin (Manis pentadactyla) has been at the top of the supply chain for illegal international markets across Southeast Asia. It continues to be the state with the highest number of pangolin seizures in India.

A 2020 report published on Science Direct states that 21% of pangolin seizures between 2009 and 2018 in India were from Manipur, followed by Mizoram and Assam. An average Chinese pangolin has between 509 and 664 scales, with a combined dry weight of about 467 grams. Imagine the number of pangolins it took to produce 3,248 kilograms of pangolin scales that have been recovered in Manipur alone, and this is only from what has been reported or seized by authorities.

“It’s not just pangolins that are exchanged in the borders. Other wildlife, including marine trophies too reach Manipur as a transit to the international market,” says Jose Louies, the CEO and Chief of Enforcement at WTI.

Team WTI has also begun training border enforcement agencies and forest officials to help curb the trade. The trainings involve wildlife article identification and understanding the various facets of the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972 to be able to better investigate a case and achieve a better conviction rate for offenders in court.

The team aims to expand and replicate the ban that is currently in place in the 230 Tangkhul Naga villages in other communities and tribes, across the region. The people of Manipur should unite and work together to protect the pangolin. As for communities like Chingjaro, protecting the pangolin might as well be their first step into the conservation of their local wildlife. After all, it’s not just the pangolins that ensure that the mountains of Manipur thrive.

This article is written by Madhumay Mallik — a conservation writer, photographer, and graphic designer, currently engaged with the communications team at the Wildlife Trust of India.

Edited by Pranita Bhat; All images courtesy: Madhumay Mallik

No comments:

Post a Comment