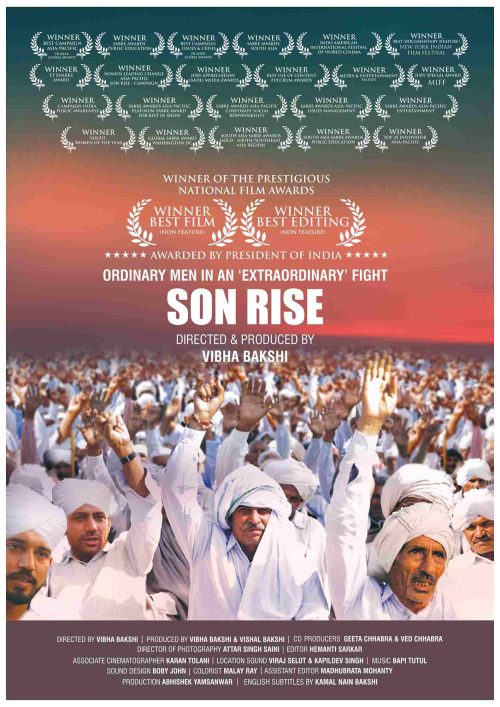

“From where do you get the courage to do what you do?” one adolescent in the audience asked multi-award-winning filmmaker Vibha Bakshi following the screening of her documentary ‘Son Rise’ (2019) — which follows the journey of men breaking the shackles of patriarchy in Haryana.

Acknowledging that it takes a great deal of pluck to speak truth to power, Bakshi was stunned when the boy continued in earnest, “I want to have the same courage to have these conversations at home, and I know they might not always have a positive outcome.”

Did she ever fathom Son Rise would create whistleblowers of patriarchy? No.

But, going by her observations over the last three years of the film’s screening across 71 countries as part of the UN’s global #HeForShe movement, the boy is not alone in wanting to fight gender bias. The sentiment is mirrored by police officers, CEOs of multinational corporations, the elite, as well as those in rural hinterlands, she has remarked.

Always one to target the status quo through layered rhetorics, Bakshi says Son Rise was a step in the same direction. The narrative isn’t preachy; there is no moral policing. Instead, the cinematic masterpiece makes the most of its 50 minutes to leave the audience with some food for thought. The film uncovers the gendered realities in Haryana by shedding light on the changemakers instead of the perpetrators. And this is what sets it apart. It beckons you to look towards the light.

Though every screening ends with thunderous applause and Bakshi’s shelves are laden with awards — including India’s highest cinema honour, the National Film Award for ‘Best Film’ (non-feature) and ‘Best Editing’ (non-feature), as well as the Global SABRE Award (2022) — the validation Bakshi values most comes when men approach her and say, “What’s happening is not right. What can we do?”

At the heart of every film of hers is a wish, a hope, a prayer for a world where men become allies and women don’t need to fear.

‘Gender inequality is not limited to hinterlands’

A dhoti (wraparound cloth worn around the legs) and chequered scarf protect the men of Haryana, as they sit in clans, sipping hot cups of chai. The camera pans to the oldest among the group, possibly in his sixties.

“They don’t let girls be born,” he reaffirms the state’s reputation for female foeticides. Another from the group chips in, “They do ultrasounds to peek into the womb.”

Are ‘they’ successful in these killings? We don’t need to look to the men on screen for answers. Statistics point us in the direction of a skewed sex ratio.

In 1901, the state had 867 females per 1,000 males in its total population, as per the Statistical Handbook of Haryana 2020-21. Over 100 years later, as per Census 2011, the state’s sex ratio remained equally worrying at 879 females per 1,000 males. These are proof of the antiquated practice of sex determination in Haryana, that continues far from the glare of modern medicine.

Pre-birth discrimination, female foeticide, forced abortions, and gang rapes that culminate in murder are rampant in the state — making for a host of ‘sensational’ topics that Bakshi could have wielded to her advantage for the documentary. But she decided to turn her gaze instead towards the revolutionaries who were setting the stage for change.

As a documentary filmmaker, Bakshi feels an inherent responsibility on her shoulders. Her films, she says, have an onus to prick the collective conscience. After all, this is the silver lining of documentaries; they don’t back down until they force you to introspect.

‘Depicting the male gaze is up to you’

The Bechdel test — a brainwave of graphic novelist Alison Bechdel — is a way to measure how women are represented in movies and other forms of fiction. When a Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS) study, published last year, applied the test to 25 ‘box office toppers’ and 10 ‘women-centric’ Hindi films, it found that only 36 percent of the blockbusters passed, while all the women-centric films passed the test. This ties in with the ‘male gaze’ — the objectification of women in cinema — that many hypermasculine Bollywood films are guilty of.

So we asked Bakshi if it’s tough navigating morally right ground while also attempting to tell a story that appeals to an audience. “It is the director’s discretion,” she asserts. “It is easy to veer towards cheap headlines when covering burning issues. On the other hand, sensitising the audience is tough,” she adds.

50 countries pledge for a safer & equitable world at the screening of Vibha Bakshi’s ‘Son Rise’ @expo2020dubai #nzpavilion #IndiaPavilion #UNHub #WomensPavilion @unwomenindia @UN_Women #16DaysofActivism @MaherNasserUN @cgidubai @SonRiseTheFilm pic.twitter.com/vWCyu95d9g

— Vibha Bakshi (@VibhaBakshi) December 4, 2021

Refraining from glorifying the male gaze or any gaze, for that matter, in her narratives, Bakshi says the message she wants to drive home is that of ‘hope’. “Without hope, no fight can be won and this [patriarchy] is a fight we cannot afford to lose.”

In documentaries, she says this is all the more of the essence. Illustrating instances of where she had to make a judgement call, Bakshi takes us back to 2015 when she was filming her National Award-winning documentary ‘Daughters of Mother India’ (2015) in the aftermath of the brutal gangrape and murder of Nirbhaya.

“We gained access to the Delhi Police right after the incident. Naturally, I saw the good, bad and ugly of the case,” she shares. While she could very well have chosen a narrative that was fodder for controversy, she decided to look instead towards the radical changes the judiciary was implementing. She decided to tell a story of hope and courage.

‘When it gets scary, persist’

A khap panchayat in North India sees hundreds of men — staunch patriarchs — gather to pass the verdict on ‘important issues’ — murders, property disputes, and elections to the constitutional bodies. Dowry (a social evil), domestic violence, and female foeticide do not feature in the mix. Smokescreens for bolstering patriarchy, these khap panchayats are arenas where men have the final say.

So, when Bakshi stood face to face with a battalion of men, with the strapping khap leader at the fore, her worst fears were realised. “I knew I was bad news here. It dawned on me that, as a woman, I had just entered the seat of patriarchy. The khap leader was not welcoming to being questioned.”

But then she treats me to a fun fact. “He ended up becoming one of our main heroes in the film.”

The same man who defied Bakshi’s position, went on to advocate change in over 800 villages! This is what good filmmaking can do. And Bakshi, whose second name is ‘courage’, is certain of the revolutions that will follow well-made documentaries.

Vinay Shukla, director of ‘While We Watched’ (2022), too, agrees. “Undeniably Indian documentary filmmakers have taken the challenge of telling stories that matter to them and matter to their people, and delivering those stories with utmost imagination and cinematic craft. No doubt we are here because of the previous generation of filmmakers who have laid the track for us, but this generation has taken a lot of risks.”

The men in Son Rise are by no means ordinary. And neither were the roads that led Bakshi to them.

Following the success of ‘Daughters of Mother India’, the filmmaker found herself in Haryana for a screening, when a woman walked up to her with a piece of news:

“I know of a farmer who is in an arranged marriage with a gang rape victim.” Bakshi spent the next several days tracking him down. When she finally did, her first question to him was, “Why did you agree to this?” And the farmer answered her question with one of his own: “Why not?” “The shame is not hers, it is ours.”

As for his wife, the survivor who was raped by eight men and sentenced to a life of looking over her shoulder every time she left home, things took a turn after the documentary got UN recognition. Recalling that full-circle moment, Bakshi says, “At the film screening, the khap leader stood behind her, issuing a silent warning to anyone who dared to touch her.” That is the power of a documentary, she smiles.

‘The issue is the same; the packaging is different’

An article exploring how the needle is moving in favour of Indian documentary filmmakers found that while filmmakers engage with the international industry, they are finding it harder than ever to connect with Indian audiences at home. Veteran documentary filmmaker Anand Patwardhan spotlighted this, saying, “Young filmmakers pitch to commissioning agents, attend workshops, labs, and market sessions worldwide. Their films often look better and are technically advanced. But at times there is a tendency to use a cinema language and style understood by consumers outside the country.”

But what Bakshi discovered was that these issues are linked to the social fabric of every nation.

As Son Rise travelled across the globe from municipal schools in remote India to well-heeled societies abroad, it became clear how the contours of gender stereotypes are the same across borders. “Ultimately, it goes beyond being a film shot about an issue in Haryana and instead becomes a film on humanity,” Bakshi discovered.

But that being said, documentary filmmakers have to negotiate their fair share of hurdles. As screenwriter Atika Chohan (of ‘Chhapaak’ fame) shared in an interview, “For every film that has been made, there are seven to eight that were not.” This holds true with documentaries too, Bakshi agrees. Censorship, funding, and political correctness sometimes play spoilsport.

And this makes it even more important to use a voice well when you have the stage.

“The goal is to give the audience such a good experience through my films that no one shies away from making or watching documentaries,” says Bakshi.

As for the young boy in the audience, who asked her where she got her courage from, she looks him in the eye, “It will not be easy. But it is worth getting into the good fight.”

Edited by Pranita Bhat; Pictures source: Vibha Bakshi

No comments:

Post a Comment