Trigger warning: Mentions of menstrual stigma and exile, sexual exploitation, medical neglect, and death

“Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health care is the most shocking and inhumane.” — Martin Luther King, Jr.

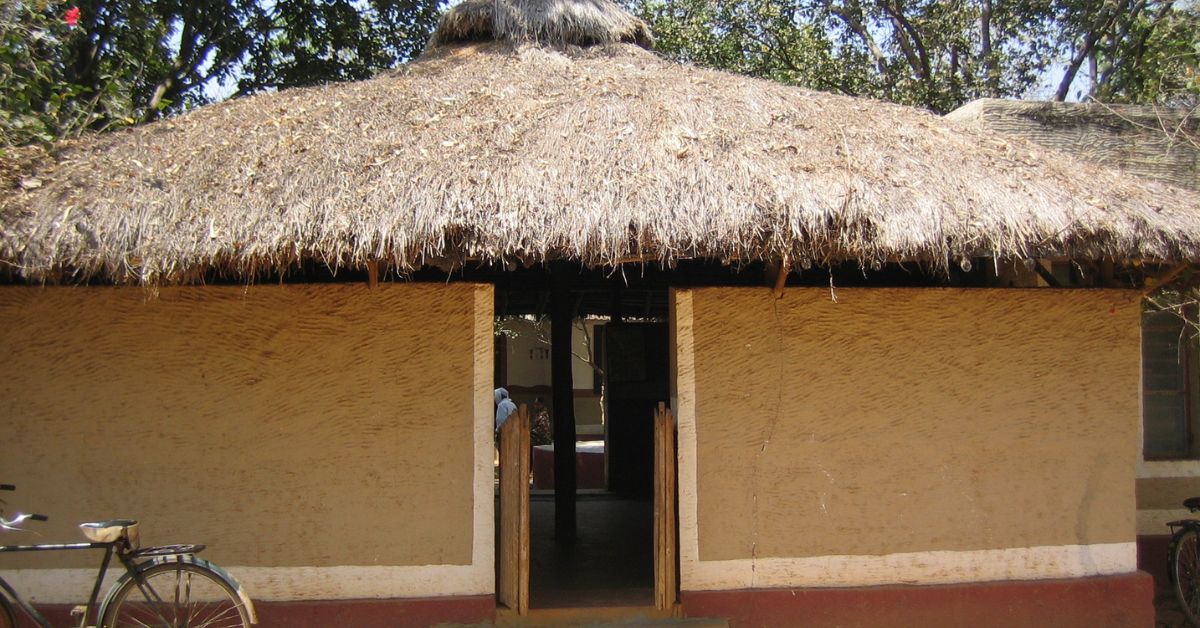

In the heartlands of Maharashtra (Gadchiroli district to be precise), lie a cluster of crumbling mud structures; bamboo and dread make up the scaffolding. The scanty roofs provide no respite from the torrential rain; the fraying walls aren’t adept at blocking out the chill. Dogs, pigs, mosquitoes, scorpions, and snakes interpret the absence of doors as an invitation to flit in and out as they please; meaning sleepless nights for the shanty’s residents — women of the Madia community who are exiled to the kurma ghar (period hut) during pali (menstrual cycle).

This inhumanity spotlights the degree to which periods are stigmatised in some tribal belts.

In 1985, when Dr Rani Bang (73), an MD in obstetrics and gynaecology got wind of the death of an 18-year-old who had succumbed to a snake bite while holed up in the kurma ghar, she was appalled. “The newly-married girl had been bitten by a cobra,” she found out. “Though anti-venom was available, no one was ready to administer it to her while she was menstruating.”

The snake bite hadn’t caused her death; a venomous ethos had.

The more Dr Rani unearthed the regressive interpretations of traditions that prevailed in Gadchiroli, the more aghast she was left. Ironically, antiquated concepts like the kurma ghar were revered. As she learnt, the edgy living setup could accommodate three to four menstruating women at a time. “The women were supposed to cook for themselves while sometimes their family members would bring them food. But they had to leave it outside the hut.” For the entire duration of the menstrual exile, the woman was not to be touched.

Within the hut, their stock of period cloths was bait for lizards and mice. And god forbid the women run out of pads, they were at the mercy of nature. Sometimes mahua (a tropical Indian tree) leaves covered in paddy chaff served the purpose; other times banana leaves helped soak the blood.

But what really amused Dr Rani was the fervour with which the women regarded the system. “They told me that they liked the days they spent at the kurma ghar because it was a chance to rest. It was one of the few opportunities they had to go to the forests and chat with their friends,” she recalls. While some women were fond of kurma because of its perks, others feared divine retribution if they defied tradition.

Well aware of how futile it would prove to uproot a well-entrenched custom, Dr Rani and her husband Dr Abhay Bang (74) decided to revamp it instead. With intervention from the Mukul Madhav Foundation, the Padma Shri couple built new versions of kurma ghar complete with modern facilities.

From Johns Hopkins to Gadchiroli

A quick scan of the couple’s achievement list leaves me in a dilemma. It boasts 72 individual accolades of national and international repute — including the ‘Maharashtra Bhushan’, the highest civilian award conferred by the State Government of Maharashtra; the first ever Distinguished Alumnus Award from the Department of International Health, Johns Hopkins University; the Mahatma Gandhi Award; the ICMR award; a shortlist as ‘Global Health Heroes’ by the TIME Magazine (2005); and ‘Public Health Champion’ by WHO (2016).

Every effort of Dr Rani and Dr Abhay — ex-chairman of the Expert Committee for Tribal Health, appointed by the Government of India to frame the first tribal health policy and recommend the design of tribal healthcare in the country — has been directed towards improving healthcare access in Gadchiroli.

But the couple isn’t lauded simply for their inventive take on tribal healthcare, but also their culturally appropriate approaches. In a region where language, culture barriers, and geographic inaccessibility pose significant challenges, and illness is often understood through spiritual beliefs and traditional healing practices, introducing modern medicine required thoughtful and respectful effort.

But as the tribes’ reluctance melted into gratitude, the Bangs knew they were on the right path. Thirty-nine years ago, fresh out of the premier Johns Hopkins, they stood at the precipice of a sea of opportunities, each more lucrative than the other. But, an inner voice guided their next step — research is fruitful in areas where problems exist, not where facilities are ample.

This formed the backbone of their decision to head to the naxal-hit, Maoist Gadchiroli in Maharashtra. And their arrival was interpreted as a blessing. Since the outset, the couple has attempted to achieve health equity by relegating reductive healthcare to the boot and bringing in scientific discipline.

In tribal pockets across India, high infant mortality rates (IMR) continue to perplex authorities; one of the many pressing issues. Studies suggest that over 89 percent of tribal women have anaemia, while only 70.1 per cent of tribal women deliver in an institution. Meanwhile, children from tribal communities were found to be almost one and a half times more likely to be underweight than children from other communities. This owes to malnourished expectant mothers, a study found, whose findings revealed that only 25 percent of pregnant and lactating tribal women had adequate protein and calorie intake.

And the biggest killer is misinformation, Dr Rani remarked through her years of work with women in Gadchiroli.

“The four major issues that I have seen women here face are menstrual problems, reproductive tract infections that are manifested in the form of white discharge, uterine cancers, and infertility,” Dr Rani shares. She spotlights the gaps and potential solutions that will better healthcare outcomes in tribal belts.

Address the gap in knowledge

Misinformation is benign until it’s not. As Dr Rani discovered, the cultural chasms of health are deep-rooted. Her conversations with women in Gadchiroli revealed that many of them consider ‘heavy menstruation’ — that most doctors would term ‘dangerous’ — as a sign of healthy physiology.

“In their opinion, scanty or normal menstruation indicates that the blood is collecting in the uterus, forming lumps, and will eventually impinge on their vital organs and cause death.”

This lack of proper diagnoses extends to children’s healthcare as well, she figured. “Initially, when we started working in Gadchiroli, the infant mortality rate was 121 per 1,000 (indicating that 121 out of 1,000 children would die before reaching the first year of life). The number one cause was childhood pneumonia.”

So, she along with Dr Abhay trained the village health workers to diagnose and treat the condition. This significantly reduced the infant mortality rate by 60 percent. “The model was accepted by the World Health Organisation (WHO), UNICEF and all the international organisations,” Dr Rani is evidently proud; the model has been adopted by 16 countries across the world.

The couple did not stop there. They realised that 60 percent of infant deaths are due to sepsis. “So we started educating village health workers ‘Aarogya Doot’ (Health Messengers) to detect and treat neonatal infections. This brought down the infant mortality rate to 20 per 1,000.”

Educate adolescents about sex education

Criminal abortions, Dr Rani highlights, are not just atrocities limited to tribal areas. Their grip extends to rural villages too.

“Sticks and local herbs are inserted inside the uterus causing contractions. The patient is forced to abort,” Dr Rani explains. Though resulting in the desired outcome, the sticks are infective, causing sepsis to set in and subsequent death.

But there isn’t a need for these reductive and out-of-touch procedures, Dr Rani highlights. “Since 1971, India has legalised abortions with the introduction of the Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) Act.”

She also shares a horrifying discovery proving that criminal abortions are true to their name for more reasons than one. “These procedures were usually done by male ‘quacks’ who would extract money from the woman and her family. Post the procedure, they would indulge in a sexual relationship with the woman,” she laments.

Through their advocacy programmes, Dr Rani urges doctors and medical workers to take cognisance of these outmoded sensibilities.

Train more doctors to conduct caesareans

Do you remember the very first case that you dealt with? I ask Dr Rani.

Her memory, I deduce, is perfect, as she recalls being called upon by the district hospital to attend to a pregnant woman in distress. “Her labour was obstructed and prolonged. I checked for foetal heart sounds, they were absent.”

A judgement call told Dr Rani she had to perform an emergency C-section. The foetus had died but the mother could be saved.

As she scrubbed in on the surgery, she was oblivious that she was creating history; Gadchiroli remembers this as the first C-section the district witnessed. Soon after this episode, news spread in Gadchiroli — “A doctor is here who can help expectant mothers live.”

These and other cases made Dr Rani aware of how crucial health education is for traditional birth attendants. “They are the ones who conduct deliveries and must know what is a normal delivery, what is abnormal, and how to conduct C-sections,” she explains.

Through SEARCH (Society for Education, Action and Research in Community Health), the Bangs have extended their reach to 269 villages in Gadchiroli. Their initiative ‘Muktipath’ — a collaboration between SEARCH, Tata Trusts, the Government of Maharashtra, and the people of Gadchiroli — is a comprehensive programme aimed at raising awareness about the harmful effects of tobacco and alcohol. It also works to foster a social environment that discourages their use and supports the rehabilitation of addicts. The programme is currently active in 200 villages.

The impact of their work must probably be infinite, I think. Dr Rani confirms my beliefs when she adds that she and Dr Abhay treat one lakh patients every year in Gadchiroli and neighbouring districts.

Prolific though their careers have been, the duo reiterate that the credit does not belong to them. The relationship they share with the people of Gadchiroli is a reciprocal one. “We feel honoured that these people have accepted us and they are receptive to our health care. We are the privileged ones.”

Edited by Pranita Bhat; All images courtesy SEARCH

No comments:

Post a Comment