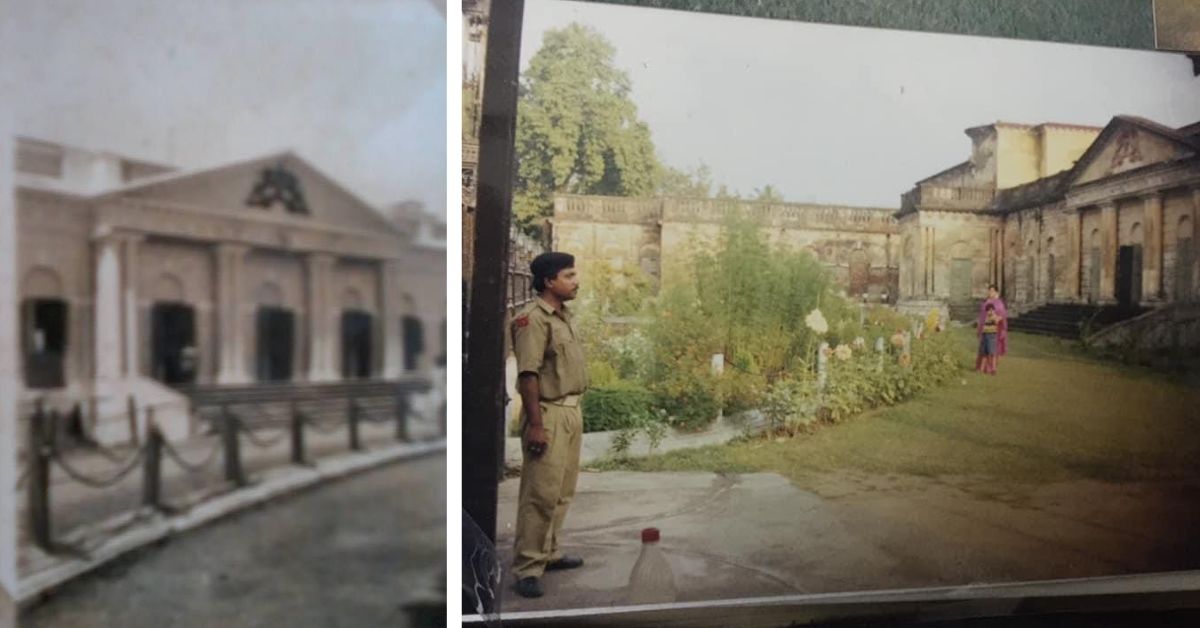

The palace was overgrown with brambles; the manor barely visible through the forests that threatened to suffocate it. Even the highest points of the castle hadn’t been spared. Wild plants held the towers in a vice-like grip. In some places, the roof had crumbled; in others it had shattered, closing off entrances and exits. No one knew for sure what the house held within it. Were there wild beasts lurking inside? Or something more ferocious?

As much as it sounds like an excerpt from one of Grimm’s Fairy Tales, the incident is a real-life scene that awaited Pallab Roy (60) and his family when they revisited their ancestral palace in Kasim Bazar, Murshidabad, West Bengal. The 300-year-old architecture had fallen into a state of despair since its last occupant, Pallab’s grandfather Raja Kamalaranjan Roy, passed away in 1993.

Pallab has my unwavering attention as he narrates his story, a tale that takes me back to an Enid Blyton adventure. He, along with his parents Prosanta Kumar and Supriya Roy, his wife Sudeshna, his son Saurav, and his daughter-in-law Priya, would in the coming days take upon them the arduous task of restoring the Cossimbazar Palace of the Roys (Rajbari) to its former glory. The goal was to turn this spectral ruin into a liveable space.

‘Operation clean-up’: Battling snakes and lizards

“We began approaching one room at a time,” Pallab says as he recalls the renovation process. However, it was only when ‘operation clean-up’ commenced that the family could ascertain the extent of the devastation. The years of isolation had taken a toll on the royal beauty.

Insects, five-inch thick layers of dust and crumbling roofs marred the family’s efforts to restore what had once been a symbol of grandeur. “The place was infested with snakes and monitor lizards,” Pallab exclaims.

As the family scoured the rooms of the ancestral palace, attempting to identify the degree of cleaning each required, they were met with more surprises, or rather shocks. “Some rooms’ arches were blocked with bricks. When we managed to get into the rooms, we noticed that the doors and windows had vanished. We guessed that they had been vandalised or eaten by termites. Even some of the supporting beams were missing,” Pallab recalls. The cleaning spree went on for years, yielding three rooms that were deemed fit to live in.

Initially, the family decided to turn the ancestral palace into a guesthouse. However, Pallab explains that the plan flopped as social media wasn’t as popular back then and most people’s first choice wasn’t a guest house. It seemed like the 18th-century palace would remain desolate. Unable to watch their ancestral pride meet such a fate, the Roy family decided to rebuild Cossimbazar Palace as a royal residence that would soon become a heritage hotel.

‘Buckingham of India’: Reviving a lost legacy

In its heyday, the Cossimbazar Palace would have earned the ‘Buckingham of India’ moniker. Explaining the comparison, Pallab shares that the palace’s functioning was in tune with colonial times and its practices mirrored those at Buckingham Palace in England.

“The British Government had a system of administering estates through the Court of Wards if the person in power was a minor and the guardian wasn’t present. Across the 10 generations of our family, three generations have seen their owners die young. And so, for almost 45 years, the British Government administered the Cossimbazar Palace,” Pallab recalls. “My grandfather – who lost his father at the age of six months – was brought up by a British governess for six years,” he adds.

As we delve further into history, Pallab draws attention to the notable parallels between Cossimbazar Palace’s functions and those of the palaces in England. “Around 1924, the house had 200 guards. There was also the ‘Changing of the Guard’ ceremony and military drills. There were 34 gardeners, innumerable staff and nine functioning kitchens.” He laughs as he recounts the famous tea parties held at Cossimbazar Palace. “The crockery and cutlery for these were imported from England!”

But, in 1947, as India got freedom, and the estate system was abolished soon after, the fate of Cossimbazar Palace took a drastic turn.

“All the assets in our family were self-earned over 10 generations; they were not grants from the Government. But everything went away without a single paisa (Indian currency denomination); they were auctioned. I have heard stories of how everything vanished overnight,” Pallab laments.

“My grandfather would say, ‘From a king, I became a pauper’. The staff at the estate, the Government, and the system turned against him as dues, penalties, arrears, and international income issues began to surface. It was a miserable situation,” he adds.

The only solution that Raja Kamalaranjan Roy saw was to leave behind his Murshidabad house and shift to Kolkata with his family. It was here that Pallab’s parents married and a major part of his life would be spent in the ‘City of Joy’.

“My mother was just 13 years old when she got married and I was born a year later,” Pallab shares, adding that he gets his resilience and optimism from her. “She had to forgo her education when I was born. But when I started school, she resumed studying. She graduated, got a national scholarship and qualified in hotel management.”

Using her new-found knowledge and culinary prowess, Supriya started a bakery in her house that in coming years would become a brand, ‘Sugar and Spice’. A common household name in the region today, ‘Sugar and Spice’ has three factories, one each in Kolkata, Kasim Bazar and Siliguri. While the confectionery brand was one of the successful projects the family lays claim to, the other remains the restoration of the grand Rajbari.

Rediscovering Cossimbazar Palace: From obscurity to opulence

Supriya Roy’s determination got the family brainstorming about ways in which they could revive the legacy of the ancestral palace. But 60 years of neglect meant that the palace had been made void of most of its treasures. “The furniture, aside from that in the main drawing room, had vanished. We are lucky to have some of the mirrors, sideboard tables and sofas, and have restored those. But three generations of photos were lost when the house was cleaned by the Government,” Pallab shares.

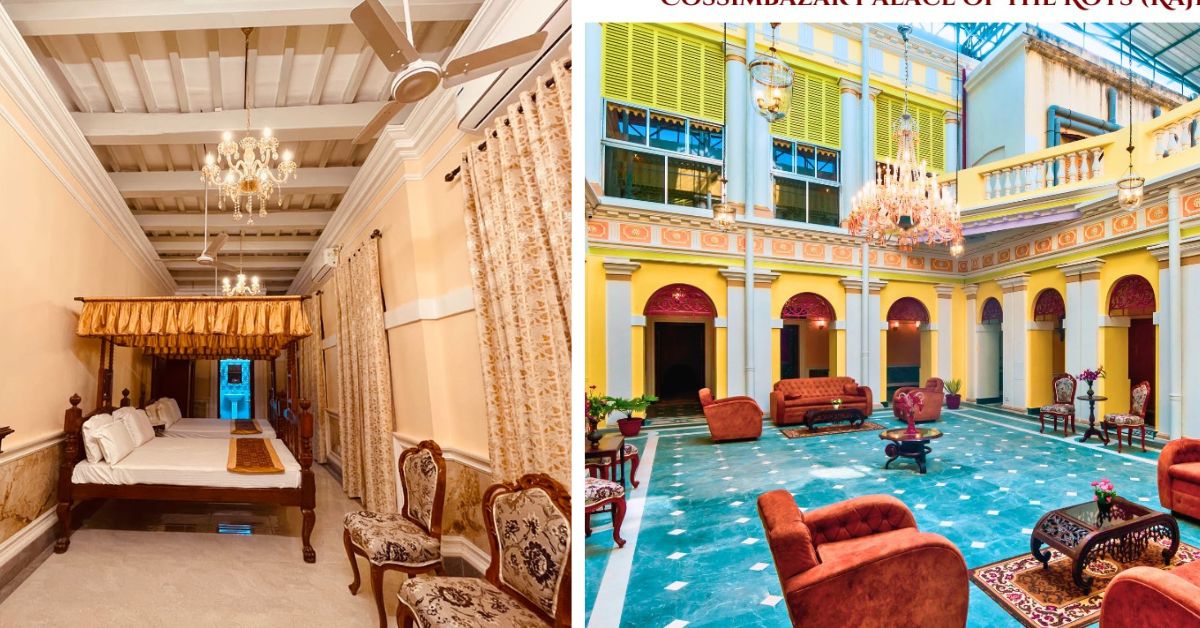

He adds that when they resolved to rebuild the ancestral property as a heritage hotel, attempts were made to retrieve these artefacts. Today, Cossimbazar Palace of the Roys (Rajbari), boasting 14 rooms, which can accommodate 40 guests at a time, is a heritage hotel recognised by the Ministry of Tourism, Government of India.

But, bear in mind, this recognition has come after decades of effort. Years ago, as the Roys vetted the situation that lay before them – a castle in ruins – they were perplexed about where to start. “The castle was a mediaeval one and so torches were popular. After the cleaning process was complete, we began work on the electricity and the wiring, the water connections, sinks and toilets. We had to replace broken furniture. And I think we changed almost 500 beams inside the palace,” Pallab says.

Taking us on a virtual tour of the magnificent space, he goes through a mental checklist of the sections of the palace that are completely restored — the front gates, the patio, the clock tower, the marble stairs leading into the main building, the north corridor, the ballroom annexes, dining room artefacts, Andar Mahal (an indoor space where the women of the palace lived), some of the temples and the interior gardens.

Such was the legacy of the Cossimbazar Palace of the Roys (Rajbari) that it has been chronicled by books such as ‘A History of Murshidabad’ by Major Walsh (1902) and ‘The Musnud of Murshidabad’ (1905). They detail the fanfare and allure that Kasim Bazar enjoyed prior to the Battle of Plassey (1757) when the city was a major trading centre and one of the largest exporting hubs in the Eastern part of India.

Giving us a glimpse of the family’s royal lineage, Pallab points to how the erstwhile British rulers used to create royalty by giving titles. “These were raja and maharaja. Our family was recognised for our charitable work and three successive generations received the title of raja.” Since this was an individual title it faded with the death of the person. This is why, Pallab explains, he and his father do not carry the title raja.

Put your royal robes on!

When was the last time you were made to feel like royalty?

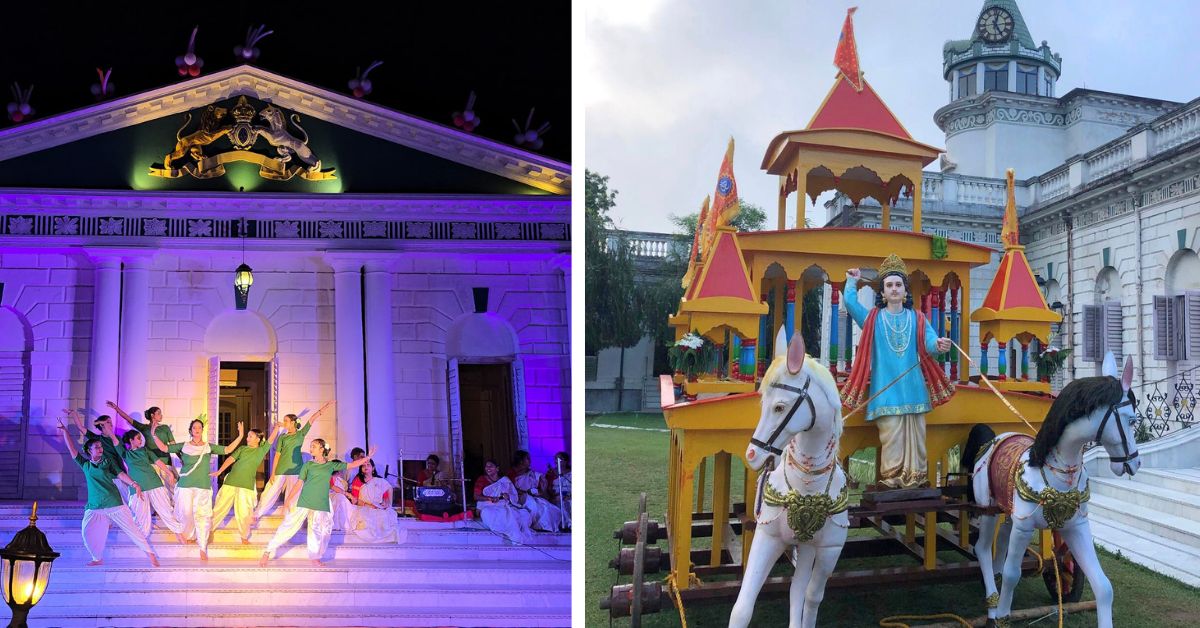

At Cossimbazar Palace, mornings are both exciting and restful. Sip on a cup of tea (or many of them) as you relish your spread of breakfast. The stillness is broken only by the sound of birds. Whether it is a session of tennis on the court, a walk around the palace gardens, or sitting by the ponds and listening to the music that drifts from one of the live band shows put up for the guests, serenity is in the details. Naturally, the guests who come to Cossimbazar Palace from around the world find themselves wishing they could take a piece of the place back with them.

“That’s possible. We have a souvenir shop where we sell local products,” Pallab explains, adding, “These include traditional handicrafts.”

If you’re trying to narrow down a date when you should plan a trip, we highly encourage 19 July. World Palace Day witnesses Cossimbazar Palace – one of the only royal residences in India to do this – celebrate in line with the palaces of Europe. “There is always a theme for the celebration. One year it was flora and fauna; the next year it was about mythology and last year they had an equestrian theme,” Pallab informs.

Once an abandoned ruin whose magic was lost in the mists of time, this 18th-century marvel has come to life once again. There is an innate sense of warmth within its walls; the events of the past decades are well behind it; there is only room for laughter and chatter now. The palace’s ‘white’ seems to brighten with every passing day. It’s almost as if it is saying ‘Thank You’.

Edited by Arunava Banerjee; Pictures source: Pallab Roy

No comments:

Post a Comment