Navigating public spaces in Indian cities is an everyday struggle for women. Ask Indu Antony, a 41-year-old feminist multidisciplinary artist based out of Bengaluru, committed to working with local communities and creating spaces for artistic expression and empowerment.

Speaking to The Better India, Indu says, “Most women I know have experienced some form of sexual harassment in public spaces. Growing up, I remember my mother giving me a safety pin, saying that if somebody touches me on the bus, I can just push the pin back on them.”

“We were always asked by our families to take precautions and equip ourselves with tools that could help us navigate a public space. This was just part of existing,” adds the doctor-turned-artist.

But there was one particular incident about seven years back that left an indelible mark on her psyche. This incident would motivate her to create one of her standout art projects — Cecelia’ed.

“I was walking on the street in HBR Layout when a couple of boys walked up to me and spat on my face. I had no idea why they did that. I had to go home and wash my face and T-shirt, which were covered in their spit. It was a scary experience. Growing up, I’ve encountered so many incidents of men touching and groping me in public but that incident was so out of the way. I just didn’t understand why someone would spit on me for no apparent reason,” she recalls.

For a brief period, Indu tried to rationalise what had happened to her. But over time, she realised that she had to stop reasoning with it and come to terms with the fact that this was not okay. She had to do something about it.

“What I came to realise is that I have the privilege, awareness, education, access to social media, and knowledge of multiple South Indian languages to communicate more effectively about what happened to me. That’s when the concept of a public art project to address the gender inequities associated with accessing public spaces first took root,” she recalls.

Called Cecelia’ed, the project was centred around Cecelia, a flamboyant single lady in her 70s. “I met Cecelia, a local celebrity, in her 70s [sometime around 2017-18] while she was cycling with a cape on. She was cycling across Malleshwaram and I saw her cape flying in the wind. Looking at her, I was like ‘Who is this person and I need to know her’,” recalls Indu.

Reclaiming public spaces

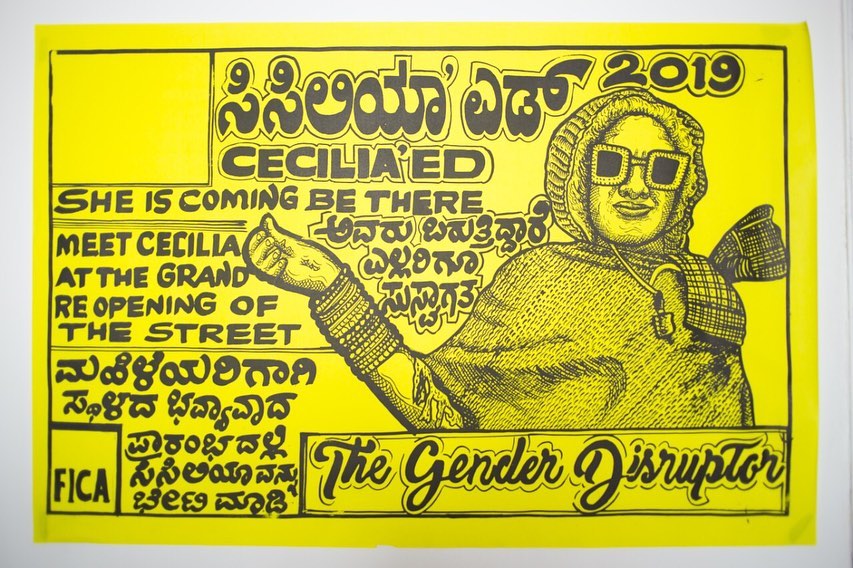

Established in 2018, “Cecelia’ed is a public art project that looks at disrupting normative notions of gender in public spaces by working with neighbourhood spaces marked ‘unsafe’ for women in Bengaluru using the politics of herd mentality and celebrity culture. Cecelia, the face of the project, was presented as a superhero called ‘The Gender Disruptor’. The project received the Public Art Grant to realise it by FICA (Foundation for Indian Contemporary Art),” she says.

“We began this project in one neighbourhood because we wanted to start from the ground up and understand issues and conversations happening there, and then move on to other parts of the city. Our first intervention was in Ward No 24 near the HBR Layout. We collected a lot of information through news, and worked closely with the local police station and gathered data from them about the locations where a lot of attacks against women happened,” she adds.

To better understand locations where women were getting attacked, Indu engaged in the study of feminist geography, which seeks to understand how urban planning is patriarchal in nature.

“For example, if you actually go out into certain parts of the city, you will see a barber shop right next to a hardware shop, a bike mechanic shop, and a paint shop with a local bar in the vicinity. Given the gendered nature of these spaces, we observed that women would look to avoid them while trying to get to a bus stop. But [at the same time] these were the spaces where we read reports of attacks happening against women in the area,” she explains.

The next step was to understand how herd mentality could be employed to raise awareness about not just her project but also how to make these spaces safer for women.

“One of the things that happens in every ward is meetings organised by local units of the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP). These are open meetings that happen with a local corporator present. We wanted local women to actively participate as citizens,” she explains.

Working alongside local printers and artists, Indu designed pamphlets that would go into the morning newspapers of local residents. The pamphlet contained information about the Cecelia’ed project and the awareness they were trying to create. They also started a local news channel, which played in different locations like the local barber shop, discussing the events taking place in the area with anecdotes from the women participating in this project.

The project’s engagement was primarily with women from the Anganwadi spaces. “I was able to talk to more grassroots [working class] women and understand what was going on with them and what were the issues they were facing. The younger women were scared of getting sexually attacked, and then the older women were more scared of getting robbed of their belongings. Either way, it was a huge burden to carry [for them],” she adds.

To further engage with these women, the project began organising workshops at the local Anganwadis every second Saturday of the month.

“Posters for these workshops were created by the women coming to these Anganwadis. We were trying to understand what the issues were. For example, they would talk about a particular street with absolutely no LED lights and whether we could get some street lights put there so it makes them a little more comfortable to walk on those streets,” she says.

“We would then write out a petition, go to the BBMP meetings, give it to the corporator, and then get these street lights actually put up in these unsafe spaces,” she adds.

Besides engagements like these, Indu and her band of volunteers also started initiatives like ‘Open Bar Nights’ as part of the project. For a woman in Bengaluru to have a drink, she would have to go to a club or pub and buy expensive alcohol. But these ‘shady’ bars with grill bars on the outside serving cheap liquor were not accessible because women never felt safe there.

“We would select a bar and take women there to have a drink. We were always faced with a lot of resistance by the men present there, but that gave us enough avenues to have conversations with them about why they were resisting our presence in these spaces,” she recalls.

Inducing celebrity culture to reclaim public spaces

An important element of reclaiming these public spaces for women was through inducing celebrity culture, and they had the perfect candidate to lead the charge.

In a 2022 TEDx Talk, Indu recalled, “In Cecelia’s case, she was already a celebrity. She had this eclectic sense of fashion. She would pick up clothes from the street wherever she could and she would put it together and post these photographs [online]. She is a single woman, lives alone, and has land sharks trying to harm her for the land where her home stood.”

As stated earlier, Indu and her band of volunteers had received information from the local police station about the spaces where a lot of women got attacked. These spaces became sites of what they would call ‘Street Reopenings’. The street was technically open but they would ‘reopen’ them with much fanfare and conversations about safer public spaces.

There were invitations sent out for these reopenings. Cecelia would arrive there in a fancy car and stand on the podium alongside the local corporator, Anganwadi teachers, and a local celebrity, and they would speak about safety in public spaces.

“We would then cut a ribbon re-inaugurating the street hoping that we won’t have any further issues on the street. We did quite a few of these interventions in different parts of the ward. These were not closed functions. Instead, they were happening right on the street. So, a lot of curious passersby would walk in asking what is happening here. We would then have people explaining to them what is happening here,” she recalled in the TEDx Talk.

“A lot of spaces where women felt unsafe had street lights that were broken. The men would get drunk, throw a stone, and break the street light. During the street reopening functions, we would get somebody from BESCOM to climb up and change the bulbs amidst claps and cheers. All the spaces where we did our reopenings were marked on Google Maps,” she adds.

Another thing they did was develop merchandise. Cecelia, a beedi smoker, had matchboxes made for her with her figure on the cover. They also made stickers and tiny dolls with her figure on them. “We also created a comic strip called ‘The Gender Disruptor’, and took this comic to schools where we raised awareness on equal access to public spaces for women,” she says.

Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic slowed down the progress of the Cecelia’ed project with life moving indoors. When the pandemic happened, a lot of the violence that was on the street came indoors. Cases of domestic violence in India and around the world spiked tremendously. In response, Indu felt that there needs to be safe spaces where women can rest and just be. This gave birth to the creation of a safe space called ‘Namma Katte’ in February 2022.

Namma Katte: Where women can just be

“Growing up, I do not have any memory of women resting in public spaces. I would see men sit and have a smoke or just get together and chill outside. But I never see women do that in public spaces like under a tree or near the radio station. It was always indoors for them. This form of public existence [in open spaces] was not there, and I wanted to change that. So, Namma Katte was an open public space we created so that the next generation of children growing up could see women resting in public spaces as a common occurrence,” explains Indu.

“As a child, I also noticed that women were always asked to do something at home — ‘wash this’, ‘cook this’, ‘make this’, ‘do your homework’, etc. As a woman, you’re constantly forced to be productive in the household, whereas I’ve seen my cousin brothers come home and do nothing. But if I were to come back home and do nothing, family members would say, ‘No, you go finish washing this or do this or that’. This bothered me and I started asking a lot of women around who also resonated with my feelings on the subject,” she adds.

Indu always wanted to have spaces for women where they feel safe and can sit and do nothing. On 28 February 2022, she inaugurated Namma Katte, which in Kannada roughly translates to ‘Our Space’. Located in one of the largest slums in the city behind the Banaswadi Railway station, “this is a space for women to sit, scream, dance, scratch, and do nothing”, open between 10 am and 6 pm every day. “It’s just a space for them to exist,” notes Indu.

“A lot of the women who come to Namma Katte work as house help in Cooke Town and other more upscale localities. After their shift, they come here to rest, sit there, and talk to other women about their day, their problems at home, and about whatever else they want. This space contains a shutter shop where you just open and be in that space,” says Indu.

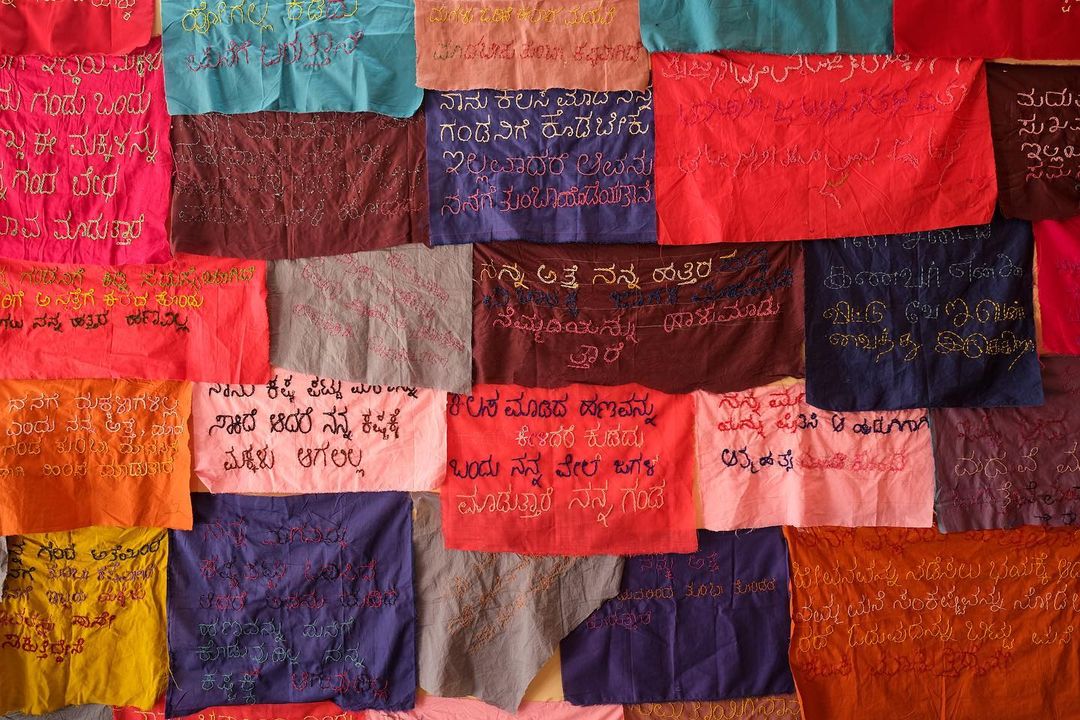

“In the beginning, we got the local women to stitch their stories that they couldn’t tell their near and dear ones on pieces of cloth,” she adds. Another important feature of this space is a swing.

“As children, we don’t have this idea of seeing women resting. The primary idea was to create a public space where women could rest, just sit around, and use the swing. It was important for us to bring back the swing for adult women. As children, your mother would hold you and perform back-and-forth movements, which made you calmer. Swings, I believe, emulate that back-and-forth movement, thus making it a perfect space for people to relax,” she says.

Despite trying to create this oasis for women in the slum, the fight to reclaim this space is constant, whether it’s dealing with drunk men or young boys playing mobile games like PubG.

“I realised early on that aggression is not going to help. Personally, if it comes to a fight or flight scenario, I’m a very fight-oriented person, but I realise in this kind of scenario that will never work. So, I would go and sit very close to these men even if they’re very drunk. I’d go sit next to them and that would make them uncomfortable. They would start moving away while I am also helping them understand why we have created these spaces. In fact, I would also agree to get a drink, go to these ‘shady’ bars, sit and talk to them,” she says.

“For the longest time, they saw me as this ‘easy woman’ but I held my ground. Looking at the greys (hair) on my head, these men had difficulty placing me. They would ask me, ‘What are you doing here?’, ‘Are you starting a tailoring shop here?’, etc. They were also not comfortable with the idea of a space where women would do nothing. I’ve had many men approach me saying, ‘Ask my wife to go home because there is a lot of work that needs to be done’. My response would be ‘You can ask your wife directly’. I always encourage conversation,” she adds.

However, in the past month and a half since Indu left for Europe to attend a series of events and conferences, some construction work has begun in the area and the men have started to crowd out the women there, especially the tree that stands next to the shutter shop. Moreover, the lady taking care of the space in Indu’s absence began enduring some problems at home.

“The challenge is navigating the gender power dynamics in that area. Namma Katte is located in one of the largest slums in the city and it’s not easy to run a space like that for women. Once I come back, I am planning to introduce some changes, including painting parts of the area and putting up signs there that if you’re a woman you can sit here, etc. We’ll see how these changes will work. I want the local women to take over the space, take ownership, and look after it,” she says.

(Edited by Pranita Bhat; Images courtesy Instagram/Indu Antony, Instagram/Namma Katte, Instagram/Cecilia’Ed)

No comments:

Post a Comment