For an art form or tradition to fade away, it only needs to be skipped by a single generation. This is exactly what happened with the ghuraliya — an instrument once played by the Kalbeliya community from Rajasthan’s Thar Desert. Many indigenous instruments and musical styles in Rajasthan face a similar risk if the current attitude towards folk artists and their skills remains unchanged, or if the youth do not take the initiative to learn and revive these age-old traditions.

Govind Singh Bhati, born and raised in Western Rajasthan, has spent the past 16 years working to preserve the state’s rich art and artists.

“Growing up, I was naturally exposed to a lot of folk music because of where I come from. My father loved playing the morchang (jaw harp) and alghoza (a pair of joined beak flutes that are played simultaneously), and my grandfather would often sit with the artists and join in,” Bhati tells The Better India.

These early experiences helped him understand the essence and significance of folk music — its origins and its deep connection to the people of Rajasthan.

A mission to preserve traditional arts for future generations

“In 2008-09, I decided to become an independent arts manager for Rajasthani artists,” Bhati recalls.

In the first few years, he collaborated with event organisers across the state and worked with institutions like the Mehrangarh Trust and Jaipur Virasat Foundation, all of which were actively providing platforms for folk artists to showcase their talents.

In 2014, Bhati, along with Sharon Genevive, launched ‘BlueCity Walls’, through which they collaborated with artists, organised shows, and conducted tours of Jodhpur’s old city — employing local residents in the process. As their work with artists progressed, the couple realised that much of Rajasthan’s folk music was slowly fading away. With the older generation passing on, the younger generation lacked a formal way to learn and preserve these traditional art forms.

“You feel the greatness between the art, the artist, and yourself, but the children are simply not learning anymore,” says Sharon, a Tamilian from Mumbai, she has been working in the social development sector for about 14 years now.

“The youth from these artist communities still want to learn and pursue music but there’s no space for them to play or learn. You’ll find hundreds of people who can play the khartal (hand cymbal) but only a handful who can play the kamaicha (a bowed instrument with a large, wooden, bowl-shaped resonator covered with skin). Same is the case with sarangi (a stringed instrument played with a bow), alghoza, and morchang,” Bhati says.

How Bhati’s Rajasthani band went viral on Netflix, reviving folk music

Bhati soon initiated projects to bring young Rajasthani voices to the cultural forefront. His first major success was the band Raitila Rajasthan, comprising seven to eight young men from folk music backgrounds. They trained and rehearsed for about six months, resulting in their debut song Mehman, which was composed and arranged by Bhati himself.

The track gained immense popularity, even being featured in the second season of the popular Netflix show Mismatched, where it went viral.

Their next project Kaisariya Rajasthan received similar response. “We basically created bands and albums that have their own identity, not just that of folk music but of true Rajasthani artists,” Bhati says.

Speaking about how folk artists have not been given their due diligence in a long time, he shares, “There is a certain perception people have when it comes to folk artists. If you go to an event organiser and say you have some folk artists who’d love to perform, the artist fee immediately cuts in half, regardless of whether the funds are coming from a private organisation or the Government. What we wanted was to make people realise that these artists are worth the money and time just as much as others are,” he says.

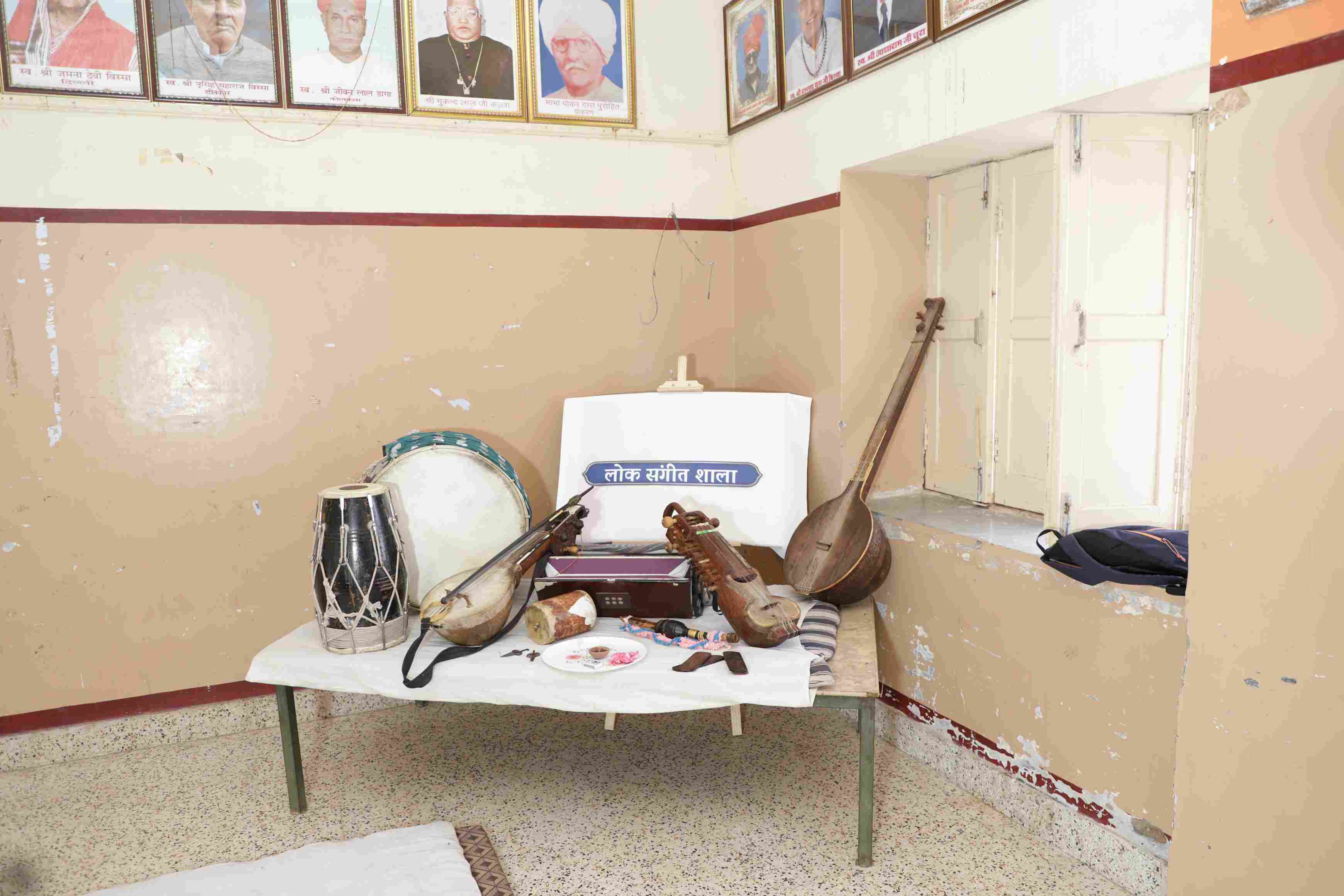

Once these initial projects gained enough traction, Bhati and his team kept meeting new people and patrons who wanted to help. “Once we got our footing right, we wanted to do something for these artists’ development also. So, we started Lok Sangeet Shala,” he shares.

Educating the next generation of Rajasthani folk artists

Launched in 2023, Lok Sangeet Shala is a fully funded artist residency where young children from across Rajasthan can gather to learn folk music from maestros and gurus. This initiative is groundbreaking because, unlike Indian classical music, there is no formal educational structure for folk music. Traditionally, it has been passed down orally through generations, with no written records to preserve it.

The residency spans seven days and includes nine classes covering various disciplines — such as vocals, kamaicha, murli (flute), tandura (tamboura), and more. Currently, the programme works with three folk music communities: Langa, Meghwal, and Manganiyars, allowing students to learn directly from master artists of these traditions.

Even dignitaries like Lakha Khan ji, a Padma Shri awardee and the maestro of Sarangi, give masterclasses here. “When I go to foreign countries or even other states to play, the reception is good because the type of people who come to watch us actually value folk singing. So, people do like it. But it is important to actually teach kids and make them understand what it means because only then will this art be able to survive,” he shares.

The residency also promotes community building, addressing the longstanding divisions between different folk music communities. Traditionally, these groups rarely interact or share performance spaces, leading to a palpable sense of hostility. However, by bringing the younger generation together in a shared learning environment, the programme helps break down these barriers, fostering mutual respect and collaboration as they freely interact and learn from one another.

“Back in the day, in our villages, artists would interact with each other at cultural events and weddings, where they would get to play night after night. But that system has ended now,” shares Bhati.

The first residency took place in Pokhran, with support from BlueCity Walls, Jaipur Virasat Foundation, and some anonymous funders. Speaking with Rakshat Hooja, the current head of Jaipur Virasat Foundation, he shares, “While Rajasthani folk music is thriving, it’s the established artists who get booked for the entire year and travel extensively. For newcomers, however, breaking into that field remains a challenge.”

The Jaipur Virasat Foundation — which focuses on the social and cultural development of Rajasthan — provided Bhati and Sharon with valuable guidance, support, and assistance in raising funds for their initiatives. “Their idea falls in line with the kind of work we do. And it was lovely to see these senior artists come and mentor young kids,” says Rakshat.

In its first year, Lok Sangeet Shala welcomed around 50 children, ages 12 to 18. This year, the number grew to 78, which included 10 girls from the Meghwal community and participants from outside the traditional folk music communities. Both of these are as rare as a cool afternoon in Jaisalmer during August.

Empowering women and healing communities through folk music

For 2024, Jodhpur’s JIET University representatives — who were present at the previous year’s showing — opened their hearts and the entire campus to provide space to these artists.

“This time, we organised the residency on their campus, where students practised in the central garden, right in front of the hospital. As a result, even patients could enjoy the music, creating a unique atmosphere of healing and cultural exchange,” Bhati shares.

He shares touching stories, like one where a son, while waiting for his father who was undergoing chemotherapy, sat and watched the students play, enjoying the music. It’s moments like these that, without a doubt, help people navigate the challenges of life.

In these traditional communities, women have often been sidelined and discouraged from taking centre stage. However, Bhati’s work has begun to shift that perception, even if just a little. For example, “We worked with Ganga and Sundar, a mother-daughter duo. To see a young woman who once lacked confidence and had never sung outside her home now performing at shows and private events is the biggest reward,” says Bhati.

When speaking with Ganga, who is as sweet in conversation as she is bold in song, she shares, “I come from a family of musicians, and I learned singing from my mother and grandmother. But I never thought I could reach this stage.”

“It’s reassuring to see young women participate in our residency, to the point where their parents trust us enough to let them attend without accompaniment,” says Bhati. This trust is a testament to the strong relationships they’ve built within the community.

Keeping the music alive: Supporting artists through the pandemic and beyond

For folk artists, their livelihood depends entirely on their ability to perform, but during the COVID lockdown, when they couldn’t take the stage, the impact was devastating for entire communities. To support them, Sharon facilitated a collaboration with My Mensa, a visual learning app, offering these artists opportunities for live music sessions. This initiative ensured that the artists were fairly compensated, while also driving increased app traffic and downloads.

“We just had to sit at home and do some of the work, so we were fine doing it for free, but the artists needed to be paid — that was our only condition,” shares Bhati.

During the peak months of COVID-19, they successfully hosted live sessions on the app, allowing every participating artist to receive compensation. This initiative also encouraged greater involvement from women, as it eliminated the need for them to travel, enabling those who had only sung for their families to showcase their talent online.

The project culminated in the creation of 50 episodes of Mehfil-e-Rajasthan, featuring around 110 artists. Some of these episodes are now available on Spotify, bringing Rajasthan’s folk music to a broader audience. “I’m just happy to be a catalyst; I connected the dots, that’s all,” says Sharon.

For those fortunate enough to experience Rajasthani folk music live, there’s an unmistakable moment when your ears immediately perk up. This art form has been perfected over generations, so deeply rooted in tradition that it resonates through your very bones. It feels as if the artists, singing with heads held high, are not performing for the audience, but singing directly to a higher power in the sky.

“It only took one Shri Ravi Shankar ji to extend the sitar’s influence for another century. Similarly, it will only take a few properly trained and passionate young people to revive the rich music of Rajasthan and ensure its survival for generations to come,” assures Bhati.

Edited by Pranita Bhat; All images courtesy Govind Singh Bhati and Sharon Genevive

No comments:

Post a Comment