“He has often said that jungle animals seem to treat him as a kind of honorary tiger — and that is what, over the years, he has become.”

I spot these words in the foreword of naturalist Duff Hart-Davis’ biography ‘Honorary Tiger’ (2005), which chronicles the life and times of ‘Billy’ Arjan Singh, also known as India’s ‘Tiger Man’.

One anecdote that lives in the popular imagination is of Billy Arjan attempting to convince then prime minister of India, Indira Gandhi, to have the forests of Dudhwa in Uttar Pradesh declared as a tiger reserve under the prestigious ‘Project Tiger’ — a wildlife conservation movement initiated by the Government of India in 1973 to boost the protection of the country’s wild cats.

After great deliberation, the then prime minister conceded. And in 1987, Dudhwa received status as a tiger reserve. Billy Arjan was thrilled; his life mission felt accomplished.

To most, it would seem almost unbelievable that this man lobbying for the protection of the striped cats was once a hunter. The slide from one to the other is intriguing.

So, what compelled ‘Billy’ — a moniker given to him by history and the locals — to dedicate more than four decades of his life to secure a safe future for tigers in India?

The answer to this lies in an incident in his youth.

The shikari retires

Born in Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh, on 15 August, 1917, Billy Arjan was raised in the then princely state of Balrampur. Owing to his father’s lineage — Jasbir Singh came from the royal family of Kapurthala, and served as a special manager for the nominal ruler of Balrampur — he was privy to the royal activities, which in those days included hunting.

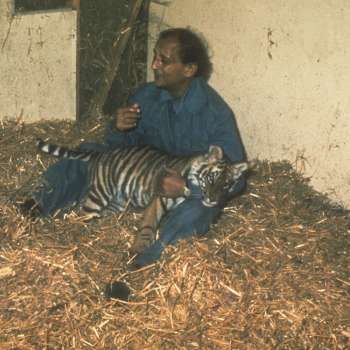

As his niece Brinda Dubey shares, “The family usually stayed there [in Dudhwa] from Christmas until New Year. It was right in the middle of the jungle and almost like living with nature. And that’s where he [Billy Arjan] grew close to the tigers.”

This was well before hunting was outlawed in 1972. The jungle formed a prized destination for hunting expeditions. And the family would often join in; Billy Arjan included.

The young boy’s targets were small animals, scurrying to escape his watchful eye. But as he grew older, his targets matured too. Soon, he was aiming at owlets, hyaenas, leopards, and tigers.

But what is more compelling than the shikari’s (hunter) exploits is the story of his redemption.

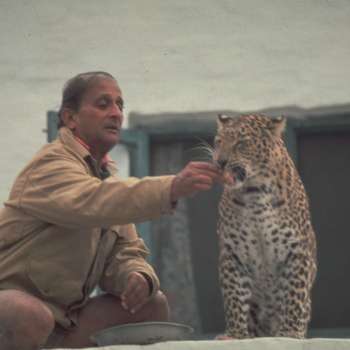

Billy Arjan recalls his forties as the last time he picked up a rifle. As he shared in an interview, “I finally stopped shooting in 1960 when I was overcome with remorse for ending the life of a beautiful leopard in the headlights of my jeep. I had no right whatsoever to destroy what I could not create.”

Tapping on this sentiment, he gravitated to the other end of the spectrum — conservation.

Unknowst to many, this spur-of-the-moment decision went on to have an outsized impact on the future of India’s wildlife conservation.

A life dedicated to the tigers

Elaborating on the poignancy of the moment, Brinda shares, “When he [Billy Arjan] shot the leopard, he saw the light in its eyes go out. That was the moment he was converted. He realised it was a dreadful thing to do; a cruel sport. He became extremely sorrowful, almost like an epiphany. That’s how he became a conservationist.”

While a buzzword today, conservation wasn’t understood as well in the 1960s. But Billy Arjan led the revolution on a piece of land in Uttar Pradesh, which came to be known as ‘Tiger Haven’, standing on the outskirts of the present-day Dudhwa Tiger Reserve.

Talking about the inception of Tiger Haven, Billy Arjan shared in an interview how the summer of 1959 was an unforgettable one. “I had gone out into the forest on Bhagwan Piari, the elephant with whom I spent 25 wonderful years. I could see the Himalayan ranges across the Dudhwa grasslands. At the confluence of the Soheli and Neora rivers, I discovered a patch of land that was owned by a politician who had lost all interest in it. I bought it and turned it into a functioning farm.”

He added that in the months to come, the farm went through a transmutation of sorts and became a haven where wildlife was allowed to thrive. To him, this act felt like “like repaying old debts”.

Seconding this narrative of Billy Arjan’s passion for tigers is Samir Sinha IFS, who shared in an interview with WWF-India, “He [Billy Arjan] held very strong views and would regularly type away letters on his trusty typewriter to flag his concerns on issues that he considered important. Though his prolific writing was curtailed due to the physical effort of typing in his last years, even with failing health, his eyes would light up at the mention of the tiger, and he was always eager to engage in efforts in support of this majestic animal.”

Sinha was referring to the years succeeding Billy Arjan’s move to Dudhwa where he began his work in tiger conservation. Those years were coloured with experiments and accolades — navigating through waves of conflict posed by communities who depended on the game and stepping closer to his vision.

‘Bring Dudhwa under Project Tiger’

When it came to the conservation of tigers, Billy Arjan wouldn’t breathe easy until he had pulled out all the stops. And the story of how he compelled Indira Gandhi to consider protecting the forests of Dudhwa puts this never-die-spirit into perspective.

Brinda tells me that the duo would often correspond with each other through postcards. She then proceeds to read an excerpt from Duff Hart-Davis’ biography, which confirms the story of Billy Arjan standing up to bureaucracy in an attempt to safeguard the tigers.

The excerpt details the proceedings of the 1969 General Assembly of the IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature) where the severity of the decline in tiger populations was stressed. The assembly went on to pass a resolution proposing a moratorium on hunting, suggesting that the income earned by shikar (hunting) companies in the past should be replaced by straightforward tourism.

“The resolution swiftly put paid to 26 hunting firms which were too high bound to transfer their activities into tourism and went out of business,” the biography mentions.

In the next couple of years that followed, Billy Arjan began to petition Indira Gandhi about the plight of wildlife in India and his beloved Dudhwa in particular. “Then, in 1972, the Government passed the Indian Wildlife Act which at last set realistic schedules and penalties, and in September that year, the World Wildlife Fund launched Operation Tiger, a global fundraising scheme,” Brinda tells me.

Leaving a legacy behind

Billy Arjan’s belief in tigers being crucial to existence is an article of faith. In the years to come, Dudhwa became a safe haven where he lived until his death, as well as a sanctuary for the wildlife he had devoted his life to saving. He was a multifaceted powerhouse who lived his truth.

He passed away on 1 January 2010, at the age of 92, but not before changing the script of conservation in India.

In a salute to his resolve, Billy Arjan was awarded the Padma Shri in 1995, followed by a gold medal by the World Wildlife Fund (1996). In 1997, he became the recipient of the Order of the Golden Ark — a Dutch order of merit; in 2004 he won the J.Paul Getty Wildlife Conservation Award; and in 2006 the Padma Bhushan, and the Yash Bharati Award.

But the glint of the awards pales in comparison to the satisfaction that Billy Arjan had each time a tiger lived because of his efforts. Today, the landscape of Dudhwa National Park — a 490 sq km park established in 1977, which connects the important tiger habitats of India and Nepal — is decorated with elephants, rhinos, over 45 species of birds and of course, tigers.

Commending his passion, Brinda shares, “The family always knew him as a person of tremendous belief. We were always proud of him.” Brinda is at the helm of affairs at Tiger Haven Society, which continues to champion Billy Arjan’s legacy.

Throughout his life, why anyone would want to hunt down an animal that is the core of the ecosystem was an enigma to him. And, till his last breath, he maintained, “The air we breathe and the water we drink stem from the biodiversity of the universal environment and its economics. The tiger is at the centre of this truth. If it goes, we go.”

Special thanks to Amith Bangre, General Manager and Chief Naturalist, Jaagir Manor, for his invaluable support in arranging interviews and providing crucial assistance for this story.

Edited by Pranita Bhat

No comments:

Post a Comment