Mohit Raj (36) an MBA-finance graduate from Uttar Pradesh recalls the first time he stepped into the premises of Delhi’s Tihar Jail. He was there at the behest of the then DG (Director General of Police) of Tihar, IPS Officer Sudhir Yadav. The latter was sure that his plan of transforming the prison reform systems in Tihar could benefit from Mohit’s expertise.

In hindsight, Mohit sees that fateful day as the one that set the precedent for the rest of his vocation; the day ‘Project Second Chance’ — a civil initiative in New Delhi that is reimagining the prisons of India — was born. Mohit spent the next many months conducting a needs assessment in jail quarters. When he wasn’t conversing with the inmates, he was observing their routines intently, attempting to understand what brought them to this fate, and how they planned on riding through it.

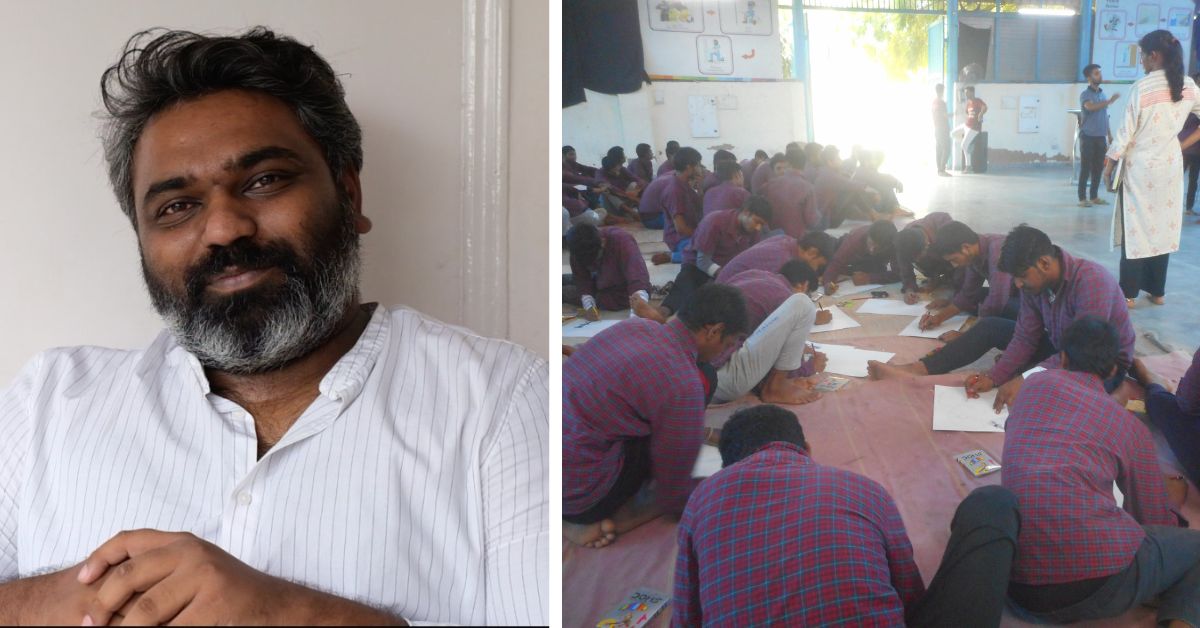

It was during those three months that a realisation dawned on Mohit — access to justice is a prerogative of the privileged. And the desire to reframe this led him to start Project Second Chance in 2017 along with Saanchi Marwaha (36) and Eleena Jeorge (30).

To date, over 11,500 prisoners have been impacted; with over 150 of them being motivated to take board exams under NIOS (National Institute of Open Schooling) and another 60 inmates employed post-release.

As for Mohit, who, once upon a time, was a young adolescent with a mind clouded with dreams of becoming a banker, the digression is intriguing. This is his story.

Care and love can transform lives

Taking us back to 2010, to one evening in particular, Mohit recalls walking back home from college in Delhi, where he was pursuing his MBA. He was accompanied by his best friend Saanchi. The duo passed by two children playing on the street, observing how a tailor, who was possibly the boys’ father, kept one eye on his children while the other gazed steadily at the machine.

“Don’t you go to school?” Mohit quizzed Ajay, the elder of the two siblings. As Ajay relayed to him, he had never been to school. His family had come to Delhi from Madhya Pradesh, where he never had the opportunity to study. “Now, no school will take me,” he shrugged. As Mohit and Saanchi discovered, schools in Delhi would only admit Ajay once his academic knowledge matched the competencies of other children his age. And so, the best friends tasked themselves with a new challenge — to prep Ajay so well, that he would be ready for school.

What started with tutoring the 10-year-old on the premises of a local temple in the evenings, rippled into a community initiative, with over 100 students — children of migrant workers who had never been enrolled in formal schooling — in attendance. In fact, 80 of them went on to clear the entrance test and were deemed competent to be admitted into schools across Delhi.

As for Ajay, he not only cleared his Class 10 exams but graduated and pursued his studies in chartered accounting. Today, he is an integral part of Project Second Chance. In fact, he’s in the next room, smiling, Mohit tells me, as he can hear his story being recounted to me.

The success of their tutoring endeavour compelled Mohit and Saanchi to travel to the root of the problem — tribal areas on the fringes of society where education wasn’t encouraged. They began setting up tuition centres in these areas under their newly-formed NGO ‘Turn Your Concern Into Action’ (TYCIA). For years, these communities had been at odds with the law; a conflict that could be traced back to British anti-tribal laws. But working at the grassroots level with the communities introduced them to the other side of things.

Saanchi says, “When given sufficient exposure and resources, the distrust in communities dissolves gradually and they bloom to create solutions tailored to their needs. They understand their context better than anyone else.”

In time, the duo cracked the code. With the right amount of care, love and treating people with dignity, they observed how communities started to develop effective solutions on their own. And when IPS Officer Sudhir Yadav heard about the work, he was keen for the model to be extrapolated to Tihar Jail.

Reimagining reforms in Indian prisons

It wouldn’t be a stretch to claim that Project Second Chance is an initiative born out of observation.

Underscoring this, Eleena makes us privy to her initial conversations with male inmates in Tihar Jail, who confided that they felt “cheated and discriminated against by the criminal justice system”. As she learnt, “Each of them was looking for a way to spend their time more productively. They wanted to experience some form of freedom. More than anything, they simply wanted to feel heard.”

But, as well-versed as they became with the concerns of the inmates, the trio agree that being ‘outsiders’, there was a limit to them being able to gauge the full extent of pain that convicts experience. “Only someone who had spent that amount of time in prison and lived that experience is capable of empathising with it,” Mohit notes. This is where Project Second Chance’s unique model steps in.

“We create leaders who can collectively think about different aspects of the prison that need to be relooked at,” Eleena shares. These leaders tap into solutions that address the nucleus of a person’s needs within prison — health, food, and access to legal aid. Integrating former convicts into their team, who merge their lived experiences with the understanding of the inmates’ needs, allows for a profound sensitivity to be brought to the process. “The goal is a more humane justice system,” Eleena adds.

Justice need not have a bias

For Saanchi, when she walked into Tihar Jail, it reminded her of something she’d once read: “A nation’s progress can be accessed from how it treats its lowest citizens.” She says, “I observed the significant role of power hierarchies. It became clear that the primary difference between those in prison and those outside is often merely a matter of circumstance, exposure, resources, education, and functional family setups.”

The controversy, she observed, speaks to the shifting ground of privilege. That day, Saanchi walked out willing to do something that would compel society to “address power imbalances and do everything it can to create a fairer, more equitable system”.

Today, Mohit, Saanchi, and Eleena are proud of their model. The success is validated by Project Second Chance’s success stories.

Take, for example, Avneesh Kumar from South Delhi. Avneesh was acquitted in 2021 after spending six years behind bars. One would think he rues those years, but on the contrary, he sees them as the time that shaped his purpose in life. “I met Eleena Jeorge, who gave me a chance to teach other inmates the basics of reading and writing.”

Once a free man, Avneesh tried his luck at a corporate job but says he did not find it as satisfying. “While teaching people in jail, I could see in real-time how people were being helped. I wanted to do a job that could make a difference in someone’s life.”

That is how he joined Project Second Chance where he started the ‘Kunji Helpline’, an idea to help ex-inmates by putting them in touch with various NGOs and government institutions that provide help with drug addiction, and mental health, whilst also helping them look for jobs in housing, cooking, cleaning, and other odd jobs.

Another stellar example is Karan who pursued his bachelor’s in social work through distance education while in prison. Once acquitted, Karan began studying the effects of climate on prisons. “If you observe closely, you’ll see that in winter, the population in prisons increases because people seek shelter. The same is the case during natural calamities,” Mohit explains. Karan is now working on creating climate-friendly prisons.

Another ex-convict, Rahul, has built the ALT (access to legal aid through technology) system connecting convicts with lawyers who offer their services pro bono, thus helping them negotiate administrative layers.

Having worked with prisoners across jails of Delhi, Dehradun and Haryana, Mohit says, the learnings have been many. But above all, it is a reminder that inmates cannot be reduced to caricatures under the name of reform. “They can’t be treated like guinea pigs made to do a variety of things while in prison.” This is where Project Second Chance is revising the narrative through different programmes.

This includes the following:

- A 24-month full-time fellowship programme focused on developing quality interventions through sessions on life skills and education in prisons.

- Project Rihai: a crowdfunding platform to get people out on bail who have completed their sentence and do not have money to provide bail.

- Project Unlearn: Context-based education and life skills intervention by young incarcerated men, aimed at ending gender-based violence and crime through intensive workshops and sessions inside prisons and communities.

- UTurn: A safe space within the prison to express and initiate dialogues on topics such as sexuality and substance abuse.

Project Second Chance has also created one of India’s first schools inside prison, which includes functional literacy, self-skill training, life skill training, drug de-addiction, and healthcare support.

While prison is often thought to underpin the notion of punishment, Mohit believes otherwise. “It is a space for correctional behaviour. Everyone deserves a second chance, including those in prison.” Project Second Chance is giving inmates a pen — and the confidence that they can write a better story.

Edited by Khushi Arora; Pictures source: Mohit Raj

No comments:

Post a Comment