When Kamlesh Joshi joined Delhi University’s Dyal Singh College in 2007 to pursue an honours degree in physics, he quickly realised two things. First, he had no real interest in the sciences and had chosen the subject primarily due to family pressure. Second, the gap between him and his peers at Delhi University was more like a valley than a schism.

Calling his experience a culture shock would be an understatement — everything about this new environment was unfamiliar to him, coming from a rural background.

Unable to cope, and despite opposition from his family, he dropped out after his first year and switched to political science at Shaheed Bhagat Singh College. But this too proved challenging: transitioning to an entirely new field (having studied science in school), and much of the teaching was conducted in English, whereas he had attended a Hindi-medium school (Saraswati Vidya Mandir, Nanakmatta, Uttarakhand). Many lectures went over his head “like a bouncer”.

When it was time to fill out examination forms, he kept them for a week before deciding which language he would write the exams in. Hindi was his comfort zone, but English was the challenge he needed to conquer. Ultimately, he took the harder route and studied tirelessly in libraries and with friends from his village who were pursuing similar subjects at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU). His hard work and perseverance paid off — he topped his class of 18 students and won a gold medal, a redeeming achievement in the eyes of his family back home in Nanakmatta.

Kamlesh then went on to earn an MBA in international business with a specialisation in tourism from the Indian Institute of Tourism and Travel, Gwalior. He assumed that a professional degree would secure him a decent-paying job, even if his career in tourism wouldn’t significantly impact the world.

A chance discussion with his JNU friends led them to question their futures and what contributions they could make to society. That’s when the idea took root: why not start a school in their village to ensure future generations wouldn’t face the same cultural and educational gaps they had? “We learnt everything under the ‘danda’ system (strict, imposed discipline), and this fear-based education only produces well-trained individuals, not well-educated ones,” Kamlesh argues.

The group unanimously agreed — they had to make a change. The next generation in Nanakmatta deserved a better, more modern education that aligns with the rest of the country and the world.

This discussion at JNU shaped the next few years for the small group of five — Kamlesh Joshi, Varsha, Kamlesh Atwal, Chandra Shekhar Atwal, and Gopal Dutt Joshi — who had ventured outside their home state for higher education, a move often discouraged by families in their village.

The early years

Deciding to start a school was one thing, but actually walking the talk was an entirely different ballgame. None of the five founders had formal training in education, financial backing, or experience working with children.

With an initial batch of 110 students and an investment of Rs 40 lakh cobbled together from various sources, ‘Nanakmatta Public School’ began operations in 2012. It started in a former orphanage with just six teachers, minimal resources, and little expertise. The only thing the founders were clear about was their mission — to provide a holistic education incorporating 21st-century skills, something they had never experienced themselves.

In the beginning, things were chaotic. Besides community support, they had nothing in their favour. But they decided to persevere.

To learn and improve, they began observing and studying other educational models. They drew inspiration from Teach for India (TFI) after being part of TFIx (TFI’s incubator programme), Aavishkaar (a science and maths centre in Palampur), and Bal Vigyan Khojshala of Berinag, Uttarakhand (supported by Pratham Science Program). They invited these and other educational organisations to their campus for guidance.

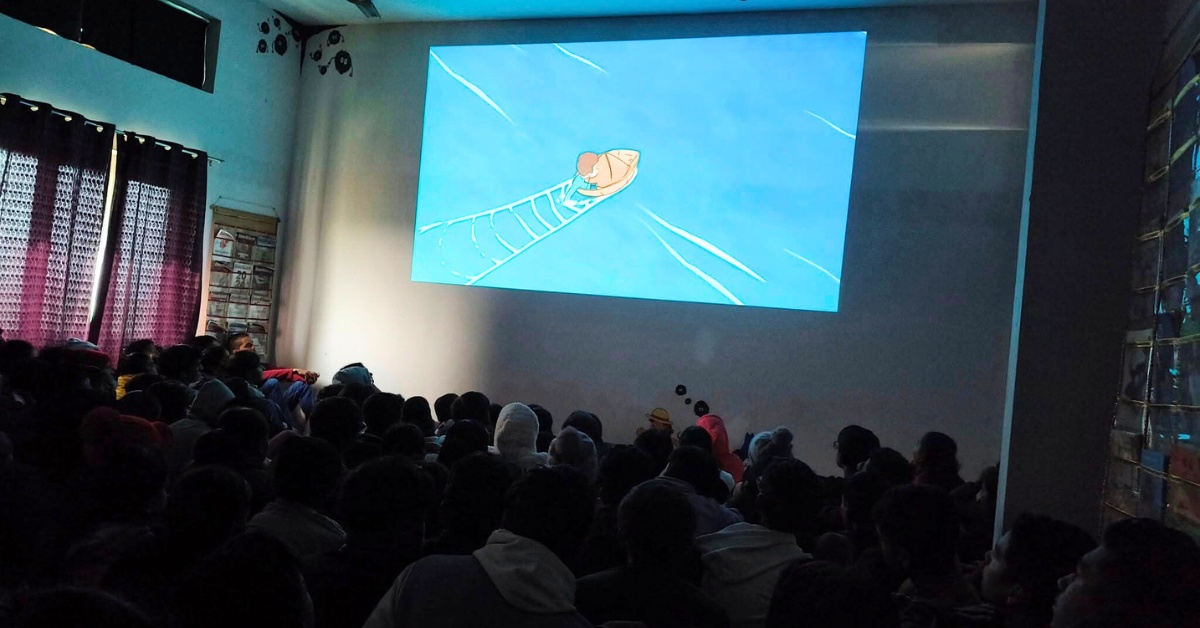

Simultaneously, they began to use films — world cinema, art films, documentaries, and Bollywood — more aggressively to expose the students to what is happening outside their immediate environs. For the last five years, they have been using cinema as a pedagogical tool to complement classroom learning under the ‘Cinema in School Initiative’, with guidance from cinema activists and educators from different parts of the country.

“We didn’t just watch the films for fun but actively debated, discussed, argued, and drew lessons and insights from what we had shown them,” explains Kamlesh Atwal, one of the five co-founders and the academic coordinator at the school. Film, he says, slowly but surely became an integral part of their learning and expression, as did field studies and research. Every single subject within the sphere of social sciences was explored and made clearer to students through the use of films.

Since Nanakmatta remains quite remote from today’s India, the school started collaborating with as many organisations outside their state as possible, so that students could be exposed to the best learning practices and feel connected to the outside environment. People’s Archive for Rural India (PARI), Teach for India, Bal Vigyan Khojshala Samiti, Pratham Science programme, Kids Education Revolution (KER), Books for All, Claylab, Joy Of Learning Foundation, Nature Science Initiative, Life Meets the Lens, among several others, were early collaborators. These organisations acted as sponges for the Nanakmatta team and teachers, enabling them to learn, imbibe, and absorb ways to further education in its entirety.

The COVID breakthrough

Oddly, when most other schools were grappling with how to keep themselves relevant during the pandemic, Nanakmatta School found its feet and began to get noticed. By this time, the school had close to 980 students and around 65 teachers and had managed to secure admission for some of its students in reasonably good institutions in Delhi and other cities in India.

Not only were the students coping well, but in many cases, they were thriving. “The pandemic allowed us to pause in our efforts, catch our breath, and share our learnings with the rest of the world in a way — on how multi-dimensional an education can be,” says Atwal, who calls 2020 a “watershed” year for their school.

The students began to teach small groups within their community while maintaining the protocols set in place during COVID-19. They started setting up libraries in their villages (a practice that continues today) and publishing a newspaper that kept everyone abreast of current events. Many videos were made and disseminated through WhatsApp, YouTube, and other mediums, highlighting the school’s innovative learning methods. These began to resonate with schools and organisations not just in India but also abroad.

Some organisations from outside even made the effort to connect with the school. One of the teachers from The Heritage Schools in Delhi, for instance, got in touch and wanted to use some of the material put out by Nanakmatta. Virtual classrooms and virtual visits from members of TFI were also organised at this time, giving the outside world a peek into the school’s workings.

The validation from those who had been in the education sector gave the founders more confidence and the energy to redouble their efforts. By then, Nanakmatta had also been formally incorporated into the TFI network, a programme under which the latter offers support to rural schools.

Doing it differently

A 15-minute film, Tharu Eco Weaves, made by the students of the school on the weaving practices of the Tharus, a tribal community in Uttarakhand, captures the essence and role played by this traditional activity in the lives of the women of the community and how it has contributed to their economic well being. Simply portrayed but professionally shot, the film was shown at the Udaipur Film Festival and was more recently dubbed into Spanish and screened at a festival in Mexico.

Another documentary film, Gold In The Net, made by the school student body made its way to a film festival in London. “The idea of using film as a pedagogical tool began to show results when our own students took the initiative and began making films that highlighted and spread awareness of local culture and practices around the globe,” shares Atwal.

A professor from Jamia Milia University in Delhi has also been working closely with the students to hone their skills in filmmaking and provide guidance wherever needed.

In 2021, when National Geographic launched a public science programme/challenge to document the biodiversity of the region, Nanakmatta School was one of the early participants. A total of 1.5 lakh different species of biodiversity were documented by the students. Even when the project expanded to 300 cities, the school was able to maintain its position among the top three, thanks to its sharp focus on environmental studies, which includes birdwatching as part of the curriculum.

In November 2024, 56 students from the school went on a week-long educational tour to Jaipur and Delhi, the learnings and insights from which were then compiled and illustrated in their school magazine The Explorer. “These collective efforts of learning and working together give our students invaluable exposure and teach them that true learning happens outside the four walls of the classroom,” Atwal points.

A journalism and social media club also help the students stay in touch with daily and relevant happenings, both in India and globally.

More recently, the school has been awarded the Wipro Earthians award for adopting and spreading safer menstruation practices among girls, who have switched to using menstruation cups rather than pads and other less environmentally friendly options.

The practice was initiated by the senior girls of Nanakmatta and is now being actively promoted by students in schools across the region. This initiative is closely guided and supported by the Nature Science Initiative Team of Dehradun, Uttarakhand. So far, students have reached out to 40 schools to raise awareness about this sustainable practice.

A School for Entrepreneurship has also been launched with 120 students, helping them understand the concept of entrepreneurship and learn to market goods made by tribal and other communities. Pankaj Wadhwa, who runs the Udhyam project that nurtures, supports, and finances entrepreneurs in Uttarakhand, believes that many of his future entrepreneurs could emerge from this unique initiative — one virtually unseen in any other schools in the state.

A small, quiet revolution

What has surprised parents, the community, educationists, and academicians across India is where the students are finding themselves after school and how they stand out wherever they go.

Almost 10 students from the school have secured full scholarships at Ashoka University, Sonepat — an achievement unprecedented for a rural school and considered harder than gaining admission to prestigious institutions such as St Stephen’s College, Delhi. Also, one of the Nanakmatta students at Ashoka University recently won the RISE fellowship and will be heading to Oxford University this year for a two-week programme.

Another student from Nanakmatta, also studying at Ashoka, recently accompanied Teach For India’s CEO Shaheen Mistri to an education conference in Malaysia as a student representative. According to Mistri, the school is doing “something very different and very right”, as she has yet to meet such self-assured and aware students from India’s rural landscape.

Additionally, 15 Nanakmatta students have made their way into Azim Premji University in Bengaluru and Bhopal, with others securing spots in good colleges at Delhi University. To help students cope with the level of English required at these institutions and develop necessary soft skills, a mentor from the Claylab Foundation (a collaborator of the school) is assigned to each student from Class 9 onwards to help them hone their language, critical thinking, and other skills.

With 95 percent of Nanakmatta students being first-generation English-medium learners, 20 percent coming from families below the poverty line, and 40 percent coming from the Tharu tribe, the school is defying all odds. A few of the early graduates are now working in high-paying and reasonably secure government and private sector jobs in metropolitan cities — an achievement that would have once seemed unimaginable to their parents.

All the validation received by the Nanakmatta school founders has led them to launch a two-year Himalayan Fellowship for Transformation, without any government support or intervention. With six fellows to start with, the programme is nurturing young leaders who can replicate this model and contribute by introducing innovative learning and teaching methods in schools across the state, which the founders argue is the most pressing need for the next generation.

Meanwhile, the school is steadily growing and now has a total of 1,350 students with a teaching staff of around 70. It has managed to break even and become self-sustaining, with fees ranging from Rs 750 (primary) to Rs 2,000 (Class 12) per month, while delivering a quality of education that many high-end private schools in India’s metros struggle to provide, despite having far greater resources.

Until recently, the Nanakmatta Gurudwara, a few kilometres from the town centre, was the sole crowd-puller in this otherwise unremarkable town. But now, this small school has become a new beacon of hope — for parents, students, and the wider community — helping the five founders realise their dream of making a difference.

As its students carve out paths once deemed impossible, this quiet revolution is turning a forgotten village into a blueprint for change, one classroom at a time.

Edited by Khushi Arora; All images courtesy Nanakmatta Public School

This article was originally published in Outlook India.

No comments:

Post a Comment