Think of an Indian musical instrument. Perhaps the tabla, sitar, or veena comes to mind — icons of India’s rich musical heritage. But beyond these well-known names, many once-revered instruments have faded into obscurity. Some were played in royal courts, while others accompanied wandering bards. Yet today, they remain unknown to most.

Here are six such forgotten treasures of Indian music.

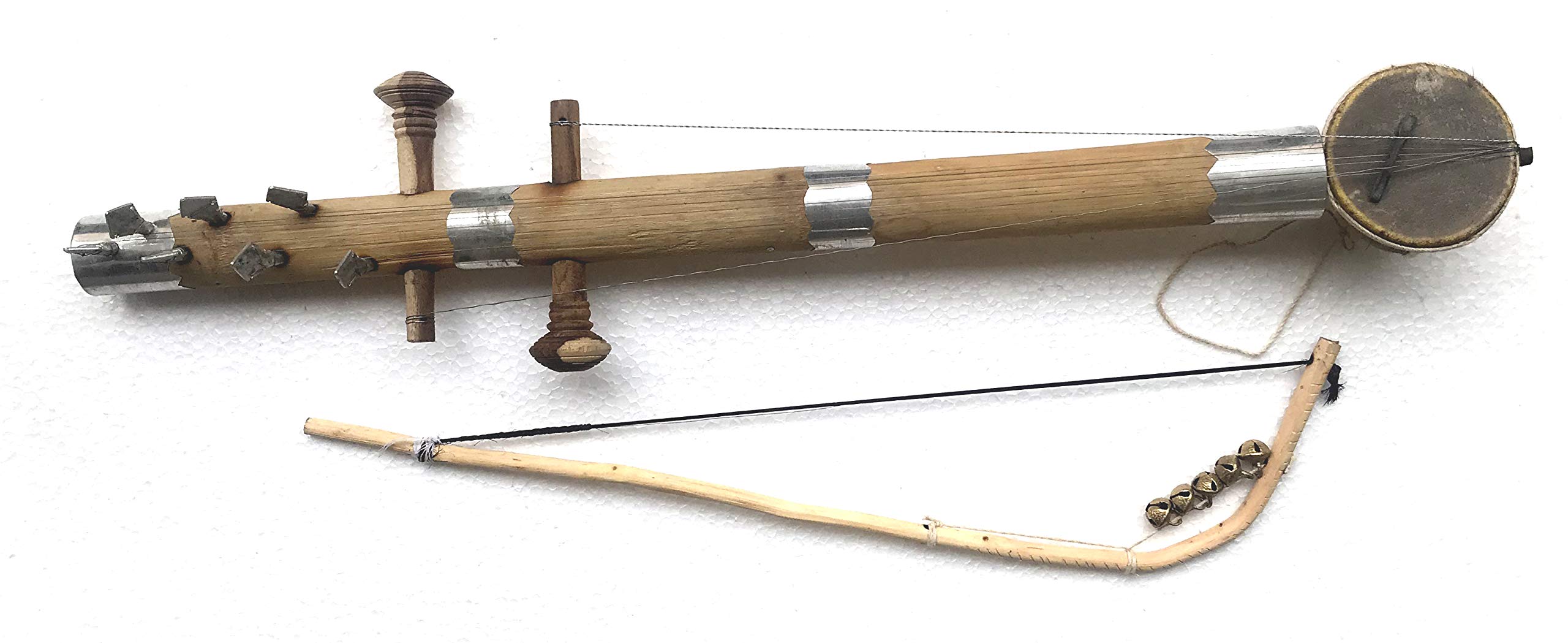

1. Ravanahatha

Age and origin:

Believed to be over a thousand years old, the Ravanahatha hails from ancient traditions in Rajasthan. Its name, inspired by the demon king Ravana, hints at its mythic past.

Where it’s still played:

Once a staple among royal bards and folk musicians, this primitive bowed string instrument survives in remote pockets of Rajasthan, kept alive by a few dedicated traditionalists.

How it sounds:

Crafted from a coconut shell, bamboo, and gut strings, its sound is haunting and resonant—evoking memories of age-old tales and secret legends whispered under starlit skies.

2. Surbahar

Age and origin:

Emerging in the 18th century, the Surbahar was developed in North India as a deeper, bass counterpart to the sitar, allowing for slower, more profound renditions of ragas.

Where it’s still played:

Once a favourite of classical maestros, the Surbahar has largely faded from mainstream performances, with only a handful of dedicated artists keeping its melodies alive in niche classical circles in parts of North India.

How it sounds:

With its larger body and thicker strings, the Surbahar produces a deep, meditative resonance—perfect for slow, intricate ragas that demand patience and devotion.

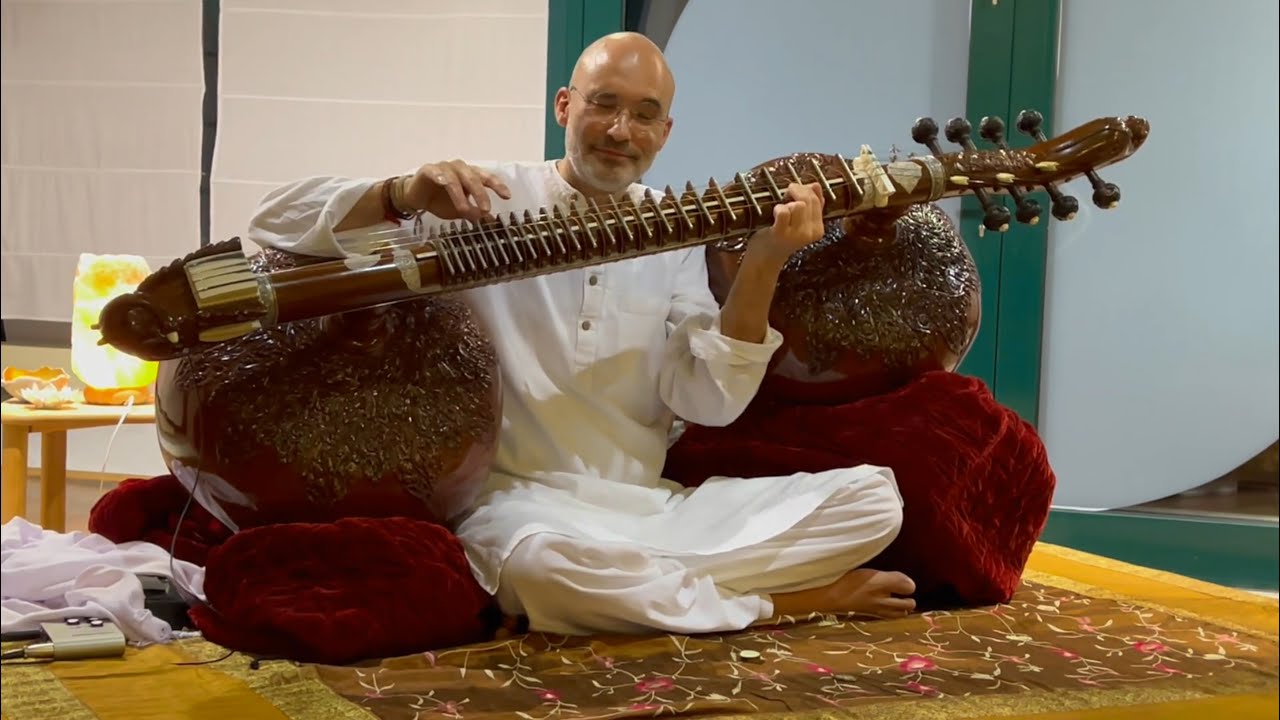

3. Rudra Veena

Age and origin:

Tracing its roots to ancient Vedic times, the Rudra Veena is one of the oldest veenas in Indian music, deeply tied to the Dhrupad tradition and spiritual practices.

Where it’s still played:

The Rudra Veena is still played in India by artists like Baha’ud’din Mohiuddin Dagar in Mumbai, Madhuvanti Pal in Kolkata, and at institutions like Dhrupad Sansthan in Bhopal and Dhrupad Gurukul in Pune, preserving its legacy within the dhrupad tradition.

How it sounds:

With its long tubular body and deep, hypnotic vibrations, the Rudra Veena creates a divine, meditative sound—reverberating with the essence of India’s oldest classical tradition.

4. Pena

Age & origin:

Over a thousand years old, the Pena hails from Manipur and has been a key part of its ritualistic and folk traditions. It is one of the oldest known bowed instruments in India.

Where it’s still played:

Once played in royal courts and sacred ceremonies, the Pena now survives through the efforts of cultural revivalists and traditional artists in Northeast India.

How it sounds:

With its single-stringed structure and bow, the Pena produces a raw, melancholic tone, perfect for storytelling, invoking deep emotions and spiritual connections.

5. Gettuvadyam

Age and origin:

A centuries-old instrument from South India, the Gettuvadyam was once a prominent part of Carnatic music before the violin gained popularity.

Where it’s still played:

Gettuvadyam, also known as Gottuvadyam or Chitravina, is primarily played in South India, especially in Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, within Carnatic classical music circles. It is performed by artists in Chennai, Bengaluru, and at institutions like the Kalakshetra Foundation and the Karnataka College of Percussion.

How it sounds:

Similar to the chitravina, this fretless slide instrument produces fluid, melodic tones, allowing for intricate microtonal expressions unmatched by most string instruments.

6. Yazh

Age and origin:

Dating back to the Sangam era (over 2,000 years ago), the Yazh was the Tamil equivalent of a harp, prominently featured in ancient Tamil literature and poetry.

Where it’s still played:

Once a courtly and devotional instrument, the Yazh completely disappeared from musical traditions. While it is not part of mainstream performances today, efforts to revive it can be seen in Tamil cultural and academic circles, particularly in Chennai and Madurai.

How it sounds:

With its harp-like structure, the Yazh was known for its celestial, delicate plucking tones — reminiscent of divine music mentioned in classical Tamil poetry.

Keeping these sounds alive

Though these instruments have faded from the mainstream, they still survive through the efforts of dedicated musicians and cultural enthusiasts. If you’re curious to hear them, you can find recordings online, attend niche classical performances, or even support artists working to preserve these traditions. With more awareness and appreciation, their unique sounds may yet find a place in the future.

Edited by Leila Badyari Castelino

No comments:

Post a Comment