On a quiet June morning in Vechale village in Maharashtra, as the wind rustles through rows of mango trees, one branch stands out—curved gently under the weight of a fruit almost forgotten. It’s not the famed Alphonso or the juicy Kesar.

It’s rarer, older, and named after a man who helped shape Mumbai centuries ago. This is the story of the Cawasji Patel mango, and the farmer who’s trying to bring it back.

At the Deshmukh family’s farm, stands a raiwal mango tree unlike any other. This indigenous sentinel bears grafts of five distinct mango varieties—a living mosaic of flavour and legacy. But this graft, in particular, tells a tale that reaches far beyond the orchard.

This mango tree, growing quietly in a rural farm, connects to the busy Cawasji Patel Street in Fort and the old CP Tank—both named after a man who helped build the city of Mumbai.

The tank, once located near Girgaon, between Grant Road and Marine Lines, was an old water reservoir that supplied drinking water to South Mumbai many years ago.

Cawasji Patel funded the construction of the water tank to address the city’s drinking water shortages, leading to the area being named after him. The tank, now defunct, is historically important as part of Mumbai’s early water infrastructure.

Patel’s legacy is tied to public infrastructure philanthropy. The Gazetteer of Bombay City and Island (1909) notes Patel’s contribution to the water project.

Back then, as Bombay grew, a mango was named after him—a tribute from a city that remembered its patrons in sweet, lasting ways.

Grown in Patel’s orchards in the neighbourhood of Powai Lake, it later spread to orchards springing up in Thane and Pune. The Powai estate had one lakh mango trees spread over 1334 acres.

The mango growing here was popular among the British as the “Bombay Mango”. In 1833-34, it was more expensive than Ratnagiri’s mango. On May 18, 1838, a basket of this famous Bombay Mango was sent to Queen Victoria of England.

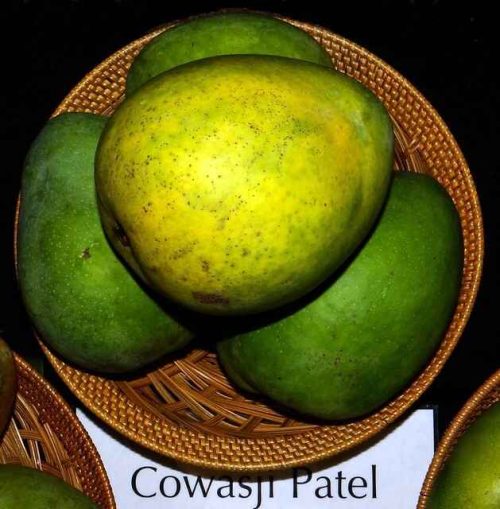

Green fruit with white pulp: What made this mago unique

The fruit was typically harvested green with white pulp, making it unique among mangoes. It was fibreless, which made it an excellent choice for cooking, especially for making jams and jellies—a quality appreciated by both Europeans and the Parsee community.

Here in Vechale, Cawasji Patel lives again—not in stone or brass, but in the flesh of a mango, sweet with memory and dripping with reverence.

Today, the variety is considered obscure and rare in Indian markets as it is overshadowed by commercially successful varieties like the Alphonso, Kesar, Dasehri, and their likes.

The Cawasji (or Kawasji) Patel mango quietly faded from view—and from collective memory.

Three years ago, Chinmay Damle, a research scientist and food enthusiast, noted that specimens from Pune’s Ganeshkhind Botanical Gardens had once been dispatched abroad and stood tall in various farms and gardens across Europe and the US.

While he overlooked the fact that the variety still exists in some Indian orchards, he did shed light on the failed efforts to export it during an era predating refrigeration.

57-year-old Deshmukh is the only custodian of this forgotten variety. “12 years ago, I was gifted a scion of Cowasji Patil, which I grafted on a raiwal (indigenous) mango tree. This June, I got 50 pieces of this variety, each mango weighed 1003 grams. But people rarely buy it as it’s unlike Hapus or Kesar, not sweet enough for our palate. But perfect for diabetics,” Deshmukh says.

Cawasji Patel: one of the few mangoes named after people

Interestingly, out of the 1,500 mango varieties found in India, only a few are named after people. Cawasji Patel shares this rare honour with a select few.

There’s Amrapali, named after the legendary dancer and courtesan from ancient Vaishali; Alphonso, which pays tribute to a Portuguese general from the 18th century; and Kesar, once known as Salebhai’s Ambdi, renamed by Nawab Mahabat Khan III in 1934.

Another well-known variety is Chausa—not named after a person, but after a place and a historic event. In 1539, after defeating the Mughal emperor Humayun in Chausa, Bihar, Sher Shah Suri renamed his favourite mango—originally called Ghazipuria—as Chausa.

From orchards to archives: The Cawasji Patel mango in global research collections

Springer’s “The Mango Genome” does mention the Cawasji (Cowasji) Patel mango variety and includes an image of the fruit, too. The book specifically notes that “hybrids were developed from the cross Cowasji Patel × Pairi, with three hybrids isolated from 153 crosses.

The Agricultural Research Service (ARS) of the United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) National Germplasm Repository in Miami, Florida, includes the Cawasji Patel mango in its collection of over 300 mango types. While listing well-known varieties from Western India like Alphonso, Pairi, and Fernandin, author Sanjana Venu also highlights Cawasji Patel as an important one.

Though the Cawasji Patel mango is no longer found in most orchards across Maharashtra and Gujarat, it is still preserved as germplasm in several important research centres.

These include the Fruit Research Station (FRS) in Vengurla, the University of Agricultural Sciences in Dharwad (which houses 67 other mango varieties), Mahatma Phule Krishi Vidyapeeth in Ahilyanagar, and the Laldhori Botanical Garden near the Girnar mountains, managed by Junagadh Agricultural University.

Laldhori’s living library of mango diversity

“The Cawasji mango tree at Laldhori is around 80 years old—a rare and regionally significant variety cultivated primarily for conservation and genetic diversity,” shares Dr Dharmendra Mehta, Professor and Head of the Department of Genetics and Plant Breeding at Junagadh Agricultural University.

Located in Gujarat’s Bhavnath foothills, the Laldhori Botanical Garden is home to over 1,000 species—from sandalwood and teak to aromatic herbs like clove, cardamom, and cinnamon. Among these, the garden also holds a germplasm collection featuring dozens of lesser-known mango varieties, including the elusive Cawasji Patel mango.

“These mangoes aren’t widely commercialised or sold in markets,” adds Dr Dharmendra. “But they hold tremendous value for research, genetic conservation, and preserving our horticultural heritage.”

Every June, Junagadh Agricultural University hosts its Mango Festival, a celebration of India’s mango biodiversity. It was at one such festival that Sumeet Samsudin Jhariya, an Indian Agricultural Research Institute (IARI) Innovative Farmer awardee from Junagadh’s Bhalchel village, first came across the Cawasji Patel variety.

“I saw it among more than 150 varieties displayed,” he recalls. “I have over 200 mango varieties growing on my farm, and I wanted a sapling—but I couldn’t get one. I still keep a photo of it saved on my phone.”

The variety that rules Gujarati kitchens

Once a household name in Gujarati homes, the Cawasji Patel mango was cherished for its large size, small seed, and sweet pulp, especially for making pickles, murabba, and chhundo. But as high-yielding commercial varieties like Totapuri and Rajapuri gained dominance, farmers moved away from cultivating this heritage mango—leading to its quiet disappearance.

“Now, people don’t even know they’ve lost something special,” reflects Dr Dharmendra.

Whether or not the Cawasji Patel is truly unmatched is a matter for debate—but its conservation, and that of other forgotten varieties, is critical.

“Preserving the germplasm—the genetic material—of traditional mango varieties is key to biodiversity, sustainable agriculture, and food security,” explains Dr Anant Morade, fruit scientist at the National Institute of Abiotic Stress Management (NIASM) in Baramati, Maharashtra.

A mango that’s connected to festivals, folk and family traditions

“These mangoes aren’t just crops. Many are tied to local festivals, folk medicine, and family traditions,” he says. “Conserving them means safeguarding cultural memory. And it must go beyond labs—we need on-farm conservation and strong community-driven efforts.”

One model of such grassroots preservation is found in Malihabad, Uttar Pradesh, where the Society for Conservation of Mango Diversity (SCMD) has made significant progress.

Their farmers’ catalogues document more than 3,500 mango varieties, keeping alive both biodiversity and community wisdom. According to Dr Shailendra Rajan, Director of the Central Institute for Subtropical Horticulture in Lucknow, 34 of these have been submitted for official recognition under India’s Protection of Plant Varieties and Farmers’ Rights Authority (PPV&FRA).

So far, over 10,000 grafts of non-commercial mangoes have been propagated—including forgotten gems like Gilas, Fakira, Taimuria, and Ramkela—now making a comeback in niche markets and fetching better prices for farmers.

And Deshmukh, who stumbled upon the Cawasji Patel mango while nurturing his orchard in Maharashtra, sums it up best: “Now that I’ve discovered something truly unique in my mango collection—something no one else has—I intend to propagate it. Not every action stems from commercial gain; sometimes, you do it purely out of love.”

No comments:

Post a Comment