Deepa recalls how tough (read: impossible) it used to be to coax her son Varun Anand (15) off the football field when he was a child. Varun loved sports. No, he adored it. So, when he was nine, and began making excuses — “I am tired, I don’t feel like playing” — to weasel his way out of playtime, his parents suspected something was wrong. In the days that followed, they watched their son become a shadow of his former self.

The lethargy persisted. It grew into an exhaustion that impaired him from completing even functional daily tasks. “I just felt tired all the time; even if I ate well, even if I rested, I was tired. There came a time when I couldn’t even walk,” Varun recalls.

As Deepa shares, “It wasn’t just his playing that was affected; whatever it was — it impacted his life. He constantly ran a fever, and his legs would swell.” But they shrugged it off as something that would “get better” until one day Varun had to be rushed to emergency care.

Dr Saumil Gaur, a paediatric nephrologist at the Rainbow Children’s Hospital, Bengaluru, recalls his first impression of Varun six years ago. “Varun was very sick when I met him for the first time. He was very weak; his bones were weak, and they were bending. His blood pressure was high, and he was having seizures and was almost in a coma.”

As Dr Saumil and the team soon discovered, Varun was battling “a silent form of kidney failure”.

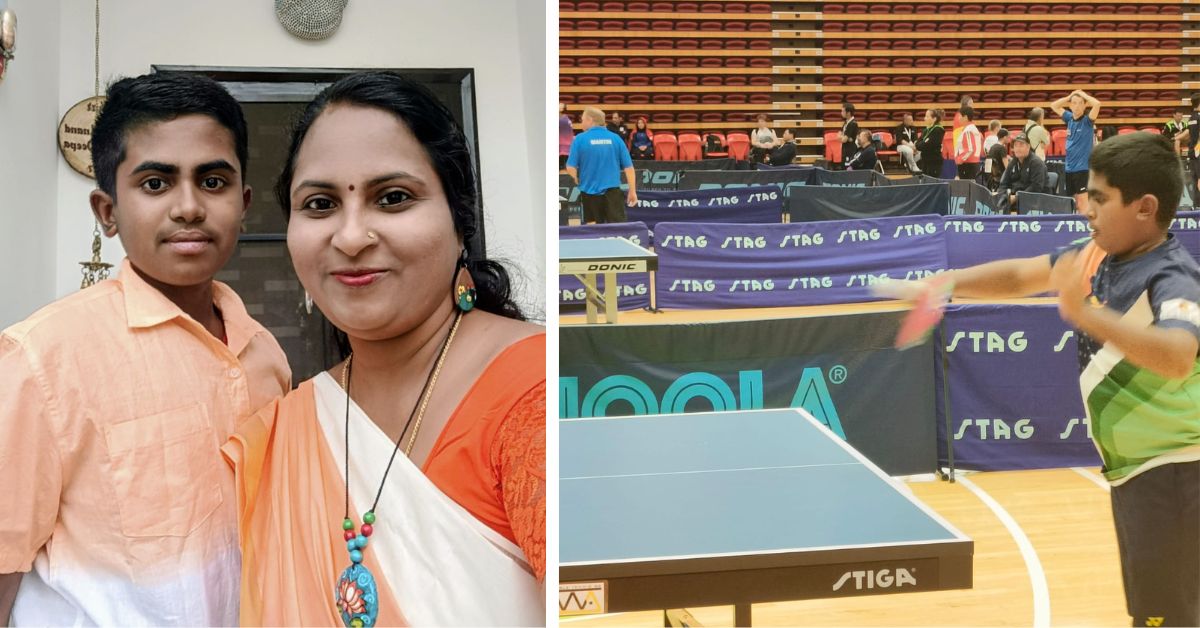

A battery of tests diagnosed him with Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD). The condition impairs the kidneys’ ability to filter blood effectively, leading to a buildup of waste and excess fluid in the body. In the weeks that followed, the then nine-year-old was put on haemodialysis and underwent a kidney transplant; his mother’s kidney proved a perfect match. Varun was nervous about how the transplant would change his life, uncertain about whether it would confine him to the stands when all he wanted was to be on the field playing.

But in 2023, at the World Transplant Games in Perth, his uncertainty about the future was substituted with three medals — gold in table tennis, badminton, and tennis in the 12-14-year age group. The transplant had given him a new lease on life. “I’d never known I had this potential,” he shares. Now, as the World Transplant Games 2025 kick off in Dresden, Germany (from 17 August to 24 August), Varun’s story shines a light on how, for those who’ve undergone transplants, sports often become the bridge helping them find their strength once more.

Where sports level the playing field

Right now, as you read this, athletes from 51 countries are gearing up to compete in 17 different sports in Dresden, Germany. At the 25th edition of the World Transplant Games (held since 1978), the entry is open to anyone above the age of four years who is a recipient of life-supporting allografts (heart, intestine, kidney, liver, lung, pancreas) from other individuals, and hematopoietic cell (bone marrow) transplants, which may require or have required the use of immunosuppressive drug therapies.

The condition is that competitors must have been transplanted for at least a year, with stable graft function, be medically fit, and have trained for the events in which they are participating.

Anika Parashar, who has enjoyed a front-row seat to the athletes competing at the games, calls the experience “unmatched”. Anika is the founder of ‘ORGAN India’, which managed Team India for the World Transplant Games 2023 and is set to do so again. Her Delhi-based non-profit organisation was inspired by her mother’s heart transplant, which held up a mirror to the flaws in India’s transplant framework.

She shares, “We struggled with finding the right kind of support and information. Despite being part of a massive healthcare company at the time, I still did not have access to the right information.”

So, today. ORGAN India wants to ensure no one grapples with the same doubts. ORGAN India has multiple ways of working:

- It increases the number of donor pledges in India through large-scale information dissemination,

- It helps anyone seeking transplants by offering information, and

- It also offers counselling services and monetary help where possible.

The spirit that fuels Team India

Through ORGAN India, Anika is looking to help more Varuns access the right treatment modalities, offering them a lifeline of hope. She recalls her astonishment at seeing Varun’s potential for the first time during their meeting at the World Transplant Games 2023. “He was the youngest among the 32-member Team India contingent but was leading it with his energy.” Being instrumental in helping transplant recipients participate in sports at a global stage makes Anika happy.

“I’ve met so many parents who’ve donated their organs to their children; I’ve met so many children who’ve had transplants. In the team, we’ve had siblings who have donated organs to each other; the generosity of spirit is just incredible,” she underscores.

Anika is a firm believer in the power of transplants, a message that’s constantly underlined by ORGAN India. Seconding the success of transplants, particularly kidney transplants in children, Dr Saumil says, there are two criteria of success. “One is the success of the graft — the transplanted kidney; the second is the success in the survival.” This implies how the person is doing after the transplant. “At our centre, the success of the graft is almost 95 percent after five years. The success of the person doing well is 99 to 100 percent.”

And Varun’s story is a case in point of a successful transplant.

‘My mom has given me life twice’

As Deepa points out, “The transplant made it possible for Varun to do more compared to what he could earlier.” Calling him a “fighter”, Dr Saumil says, “The same boy who’d been bunking PE (physical education) class in school now practises for hours in the hot summer sun.”

His resolve was tested during his training period — “In the weeks leading up to the games, I’d train for three hours on weekdays, seven hours on weekends, and the majority of the day during the summer holidays.”

A medal — much less upending expectations by winning three — was never on the cards. “My parents always told me to go have fun at the games; ‘try winning’, they said, but I remember when I held the first gold medal, I was struck by what I’d actually managed. My mother was crying; her kidney, after all, had helped me do something significant for the country,” Varun shares. Varun is set to participate once again in the ongoing games.

And off the field, he is steadily working towards his dream of becoming an entrepreneur.

The choice of a profession that constantly needs one to push the envelope most probably stems from the journey he’s had; the ‘second shot at life’ that he’s been offered through the transplant. And this is the power of transplants, Anika points out.

Beyond the ambit of sports, she says transplants help a person reclaim their agency in life. “My mother passed away five years ago, and everyone asked, ‘Why are you still doing this?’ But I tell them that, while ORGAN India was motivated by my mother, it’s not about just her anymore. It’s bigger than any of us.”

This is where she believes awareness is a core rung of the ladder. “We aim to create an impact through the programmes we conduct in villages, in schools, in panchayats (village governing bodies), and corporates. We’ve conducted these programmes in states like Haryana, Delhi, Rajasthan and done numerous campaigns.”

The other half of the battle

But while awareness is one facet of the story, there is also a healthcare infrastructure that needs to be made conducive to the transplants. According to a report released by the Union Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (2025), only 13,476 kidney transplants were performed, both in government and private hospitals, against the recommended 1 lakh cases last year.

It further revealed that the organ transplantation programme in the country has been crippled by multiple issues, especially insufficient funding, a shortage of specialised doctors, and procedural delays. Shortage of Intensive Care Unit (ICU) beds and lack of financial support to patients who require lifelong medication seem to be the biggest bottlenecks.

Early detection and screening might help bridge the chasms in organ transplantation. This is where ORGAN India comes in. By catalysing continued dialogue on the legal and ethical aspects of organ donation, the initiative is promoting awareness, helping people make informed decisions.

As Anika textures this: “In India, there are a lot of myths and conditioning when it comes to organ transplant. We work under the aegis of NOTTO (National Organ & Tissue Transplant Organisation). The data of anyone who registers with us goes to the government system. We’ve always been very accountable.”

Explaining the process, she says, “If I want to sign up to be an organ donor, I can go on the ORGAN India website and express my intent to donate my organs. Once I fill in the details, it goes into the system. Once you are registered as an organ donor, you talk to your family and tell them about your wish to have your organs donated in the case you are ever brain-dead.”

And by signing up to become a donor, you are helping people like Varun get a new lease on life. In his words, “For me, getting the transplant was like a new chapter beginning. I closed the old book, and the transplant helped me write a new one.”

All pictures courtesy Deepa

No comments:

Post a Comment