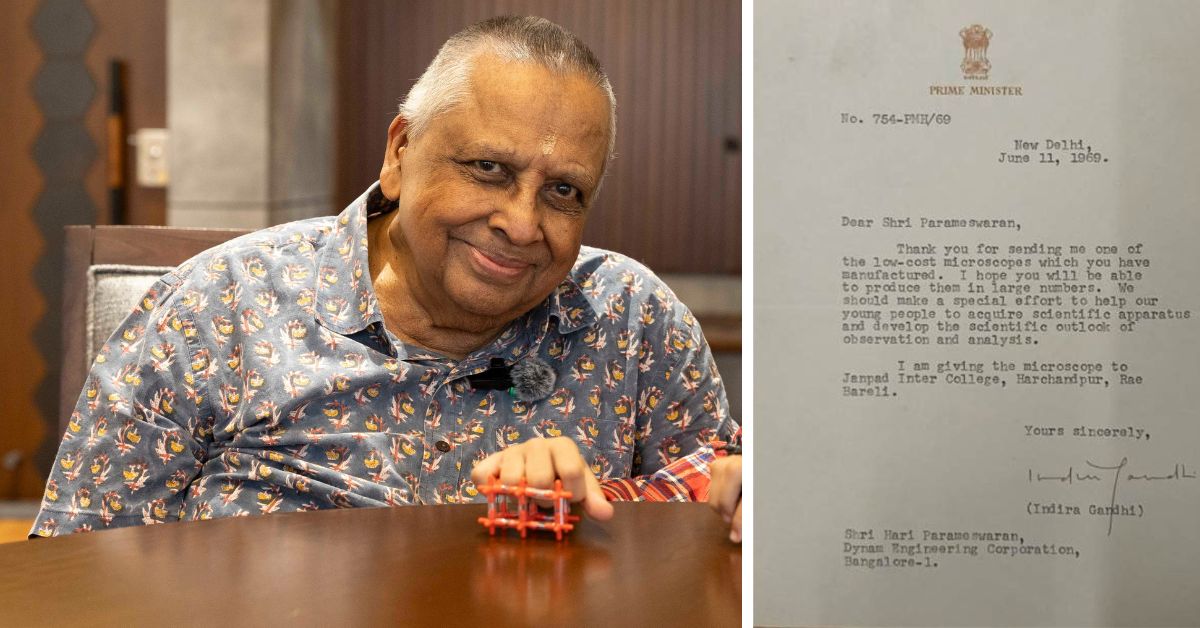

“Thank you for sending me one of the low-cost microscopes which you have manufactured. I hope you will be able to produce them in large numbers. We should make a special effort to help our young people acquire scientific apparatus and develop the scientific outlook of observation and analysis.”

I don’t know what thrills me more: that I’m privy to a letter penned by former prime minister Indira Gandhi in 1969, or that I’m holding the said microscope in my hand. As I allow my fingers to graze its bright green contours — the 7.8 cm x 1.6 cm beauty is snuggled in my palm — its creator Hari Parameswaran (84) watches on.

Allow me to introduce you to Hari, a bona fide genius who has 25 patented science kits to his name; wakes up religiously at 3.30 am — has done it for as long as his memory allows him to backtrack — and is what most people would call a ‘prodigy’.

It’s quite intimidating to be in the presence of this force of nature. So, you’ll empathise with my nervousness when he asks me to give the Dynam Mini Microscope a try, handing me a slide (a thin, flat piece of glass that holds a specimen).

I fiddle. He watches.

I sense there’s a specific reaction he’s awaiting. The ‘wow’ that escapes me exactly three seconds later seems to do the trick.

I have aced the test.

My reaction wasn’t preordained. I’ll explain: During my years pursuing biomedical science, I dreaded microbiology practicals. Try as I did, my slides — blood and cells, a far cry from Hari’s cross-sections of leaves and fabric — always seemed a blurry maze. Microscope and I, not a good idea, I’d come to believe. But Hari’s little experiment had proved me wrong. That, coupled with the genius of this tiny device in providing magnification comparable to a traditional microscope, transforms me into an instant fan.

As Hari explains, my awe mirrors that of the thousands of children who’d tried their hand at this ‘world’s smallest mini microscope’, which in 1992 received the Worlddidac Gold Award that recognises innovation, quality and practical application of teaching materials. The Worlddidac Association is headquartered in Bern, Switzerland, and the awards are widely regarded as the Olympics of the educational materials world.

But the microscope isn’t Hari’s only invention.

Under Dynam Engineering Corporation, incepted in 1963, Hari has been attempting to reengineer children’s archetypal notions about science, build windows into the boxed academic realities that constrict their imaginations, and transform ennui into delight.

Hari Parameswaran: The making of a science maverick

We journalists are taught to put claims in quotes. It’s an expert’s word against ours.

But, I’ll sidestep the rule just this once.

There isn’t a place in this world more suited to befriend science than Hari’s home in Bengaluru. The two hours I spent with him taught me more than any science class; trust me, I’ve taken a lot of them.

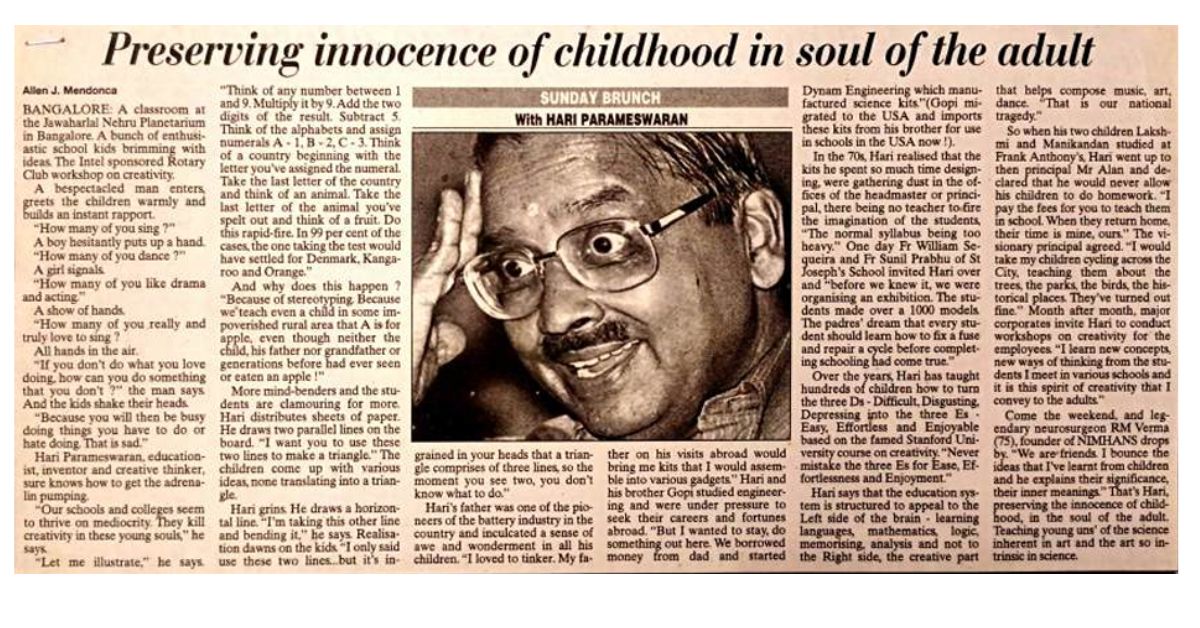

I paraded around the room with hangers perched on my head to understand the centre of gravity; whirled lidless glasses of water in wide circles to learn about centripetal force; and flew paper planes across the living room to understand aerodynamics. Hari’s home workshop is a maze of colours, shapes, and scientific apparatus. Elsewhere in the world, such scenery would deter someone, but not here. Here, science is a friend. It’s a playground for creative abandon.

Hari’s patents and design copyrights stand at 25. His awards stand at 11 (these include the National Award for best teaching aids for the Dynam Electrikit in 1971 and the Paul Harris Fellow by Rotary International for contributions to humanitarian and community service in 1990). But the chart-topper is the love he’s amassed from people; it stands at a million. As he indulges in the memories of his journey leading up to here, it’s evident that serendipity played cupid in spinning his love affair with science.

“My brother and I loved tinkering with things. The process of coming up with ideas was intuitive. We would keep finding ways to understand concepts. At school, we’d realise that we’d already done whatever was being taught in class. Once you’ve done everything with your hands and seen it, all theory takes a backseat,” Hari smiles.

For years, this mental toggling continued. “Then, we moved from Mumbai to Bengaluru to our present home (where I’m speaking to Hari). I continued to engineering college in Coimbatore. But, there too, everything that was being taught felt familiar.”

In a humorous vein, Hari recalls his once-crammed dorm full of mechanical engineering students lining up to learn from Hari. He diagnosed the problem soon; students weren’t being taught in a way that guaranteed understanding; they were being taught in a way that guaranteed marks. And so, while bending his head over experiments with his batchmates, Hari stumbled upon the leitmotif of his life’s work.

“When I returned from Coimbatore, my father asked me what I wanted to do,” Hari explains. The options presented to him were an array of lucrative master’s courses abroad — “This was a time when the trend was moving abroad post-engineering” — each more enticing than the previous. But none of them held Hari’s fancy.

“Then what do you want to do?” his father urged.

“Can I have the garage? If you give me the garage and some money, I will create teaching aids that will help children understand concepts before their teachers even teach them,” Hari replied.

And so with a garage and Rs 14,000, he started.

The space has been a silent witness to his genius.

Microscopes to electric kits: when science transcends the textbook

Suhas N fiddles around with the Dynam Mini Microscope. Instead of apprehension, excitement colours his face as he adjusts the focal length. Like me, he chooses the word ‘wow’ to articulate the joy of seeing magnified worlds through a tiny eyepiece. Suhas rarely verbalises his excitement; he has autism. But the worlds he sets foot into, while gazing through the eyepiece, make him feel seen and heard.

The microscope and Suhas are tight friends. The fact that it is unbreakable is a relief for him.

This invincibility owes to its 8 mm diameter borosilicate glass, “with no spherical* or chromatic aberration**”. The magnification is around 60 times.

Recalling the fateful day her father had this Eureka! moment, Lakshmi Krishnakumar says, “He woke up at 3 am that day with a crazy idea, woke up everyone in the house, then went to his workshops and chiselled the microscope out of wood.”

Today, it’s one of Hari’s most prized possessions.

“The microscope is always something perched on a high shelf in schools. Students are scared of using it for fear of it breaking. But I asked myself, how will keeping it out of reach get children of all backgrounds interested in it? I created the Dynam Mini Microscope so everyone, right from neurodivergent children to even a farmer’s child, would be able to learn. When will the farmer’s child learn to look for microbes in water and draw the relation between why clean drinking water is important?” Hari reasons cogently.

Suhas is one of the 200 students who’ve benefitted from the Dynam Vocational Skills Training Centre, an initiative started in 1980 by Hari, providing vocational skills training for neurodivergent children using materials fully developed in India. Here, children are encouraged to experiment.

Camps, collaborations, and community impact

Hari basks in the joy of making science accessible to children, whether through the microscope, the Dynam Electric Kit (comprising more than 40 components to understand electricity, permanent magnetism, electro-magnetism and electrolysis), the Abacus Kit (a palm sized abacus to help children understand addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division and mental math), Dynam Rotor (a rotating component in the motor kit, responsible for converting or transferring motion and energy), Centre of Gravity Kit (comprising geometric cutouts of various figures like the square, rectangle, rhombus to understand the physics concept) and Bell Kit (a kit that explores the working of the electric bell and the electric buzzer). The kits are in use across India and have also reached schools in Australia, the United States, and Africa through partnerships with NGOs and educational institutions.

Through outreach camps across Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra and Gujarat, Hari conducts science demonstrations for children who have never seen a lab. His associations with the Rotary Club of Bangalore, National Trust for Welfare of Persons with Autism, Cerebral Palsy, Mental Retardation and Multiple Disabilities (as vice president) and APD (Association of People with Disability), Bengaluru have seen him extend his knowledge to children with various kinds of disabilities. He has been an active member of the Bangalore Environment Trust and has been responsible for environmental awareness in both urban and rural schools, covering more than 10,000 children.

In addition to this, he’s helmed a unique science education programme in HD Kote, Karnataka, which sees 200 students from government-run residential schools for scheduled tribes and marginalised communities participate in an immersive, two-day hands-on science workshop. Run by Dynam Creativity with Hari Parameswaran and his team of teachers and personally funded year after year by Dr. Malavika Kapur, an emeritus professor at the National Institute of Advanced Studies, the initiative delivers kits filled with engaging, low-cost experiments covering physics, electricity, math, and motion.

Students build models like turbines and tetra-hexaflexagons, giving them a sense of achievement, confidence, and curiosity. Led by a small team of passionate educators, the programme is not just about teaching science – it’s about sparking imagination, creating joy, and showing India’s most underserved children that they, too, can be inventors and explorers.

But praise Hari, and he shies away. “It’s just hard work. When I get an idea, I don’t allow my brain to come up with negative thoughts. Our birthright is to try, and if you try and believe in an idea, it is bound to work,” he points out. These brainwaves usually visit Hari at 3.30 am. The one hour after he wakes up is sacrosanct. “Once I have the idea and I enter my workshop and touch the materials, it’s like my hands already know what to do,” he says.

Even at 84, he’s in no way ready to “sit back”. In fact, quite the contrary. Hari is attempting to scale his neural capabilities. “For the past 30 years, I’ve been writing with my left hand every morning to activate my right brain,” he explains. Having both hemispheres of the brain active will spark more ingenuity, he believes.

Complex as most scientific problems might seem, to Hari, the answers lie in tactility — in the way he cradles a lens, bends paper into experiments, works his fingers around deft contraptions, and speaks about science as if it were an old friend, one that he’d like for the world to know better.

You can check out all of Hari’s work here.

*: an optical defect that occurs in lenses and curved mirrors, causing light rays passing through different parts of the lens to focus at slightly different points, resulting in a blurred or distorted image.

**: a common optical phenomenon that occurs when a lens cannot bring all wavelengths of light to a single converging point.

All pictures courtesy Hari Parameswaran

No comments:

Post a Comment