“Can I sign up for a heritage walk? I want to get to know my city better.”

“We only take foreigners.”

The reply stumped Abu Sufiyan Khan.

After this failed first try, Abu (32) knocked on another door. This time, the tour guide obliged. But the “Wikipedia-esque walk” disappointed him.

As Abu navigated the veins of his century-old home city, his attention snapped to the crumbling havelis (manor houses), arched doorways, and the pandemonium in the baazars (markets).

But the tour guide’s walk shied away from these elements, his hackneyed monologue instead focusing only on the popular overdone spots, leaving Abu feeling a sense of loss.

The magic of his home city was fading away with every new-age rhetoric spun around it.

“To add to this, these walks kept emphasising pickpockets and unsafe roads,” Abu points out. They were vilifying the city’s reputation. So keen to tap into Delhi’s breathless routine, the walks were forgetting to pause and let the city get a word in the conversation.

But Abu wanted that to happen.

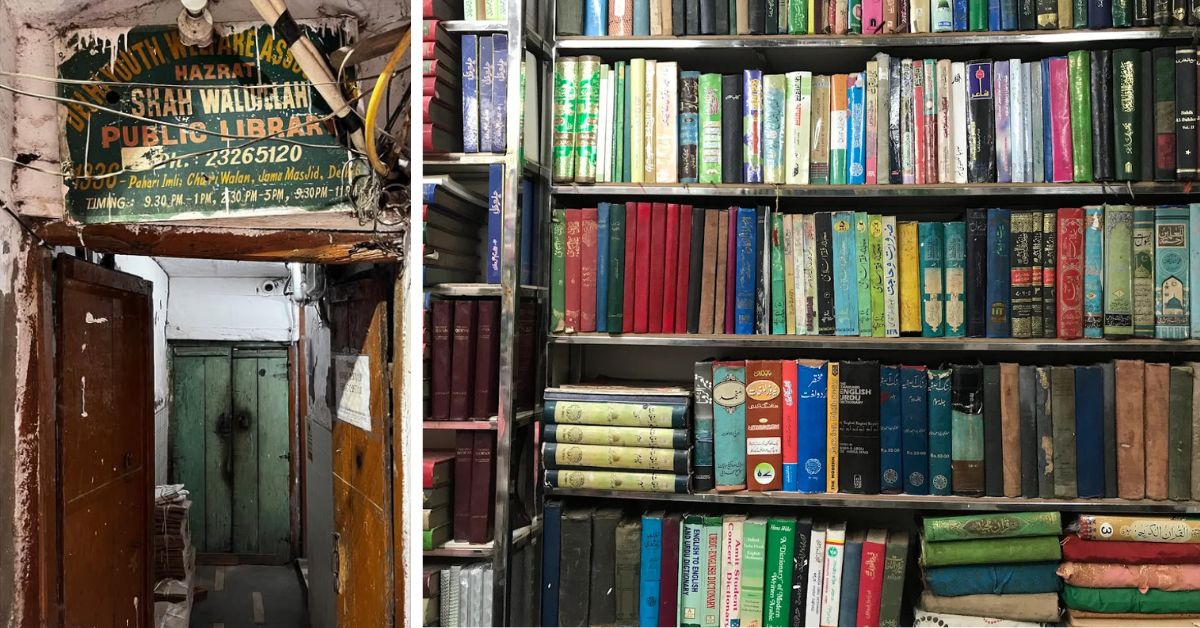

That day, he took his favourite detour before returning home. At the Hazrat Shah Waliullah Public Library — originally established as a one-room refuge during the 1987 riots, it now overflows with thousands of books in Urdu, Arabic, Persian, Hindi, and English — Abu addressed the room of readers and scholars, regulars at this reading sanctuary, one of the major Urdu libraries in Delhi.

“I want to do heritage walks,” he coaxed the gathering.

They were on board.

This was the speciality of the Hazrat Shah Waliullah Public Library.

Every idea was welcomed. Every thought was given a dais.

Ever since the first time Abu had stumbled upon the library, he’d been mesmerised by its repository of Urdu manuscripts, a priceless collection of over 30,000 books, a 100-year-old Quran embossed in gold; Ghalib’s poetic rendition Diwan-e-Ghalib, complete with his seal and signature; an illustrated Ramayana in Persian; and Diwan-i Zafar, a volume of Bahadur Shah Zafar’s poetry, printed and sealed by the royal press in the Red Fort in 1885.

Within the four walls, he’d held conversations with shayars (Urdu for ‘poet’), bantered with culture aficionados who always had a bout of trivia to share (“Did you know William Dalrymple would also visit the library, its material serving as research for his books?”).

While we couldn’t confirm that the Delhi-based Scottish historian did indeed pay visits to this reading room, Abu was quite fascinated by the likelihood of the fact.

So, with some of the most learned people of Delhi nodding to his plan, Abu started Purani Dilli Walo Ki Baatein (Conversations of the people of Old Delhi), an initiative that, since 2014, has been curating experiences (including but not limited to heritage and food walks) that act as playful homages to the classics that Delhi is known for. Its uniqueness lies in the way it introduces complex history to youngsters in a way that piques their interest.

“Hum galliyan ghumayenge logon ko (We’ll take people through the streets of Delhi),” Abu resolved when he’d started.

And that’s what he does with us, too, virtually.

When history is smitten with Delhi

Do you know about Naseem Mirza Changezi?

Naseem came from a long line of freedom fighters. He was born in 1910 in his ancestral home at Pahari Imli near the Churi Walan (bangle sellers) area of Old Delhi. One of Abu’s classic anecdotes to tell, as the group gathers around the century-old home, is of how revolutionary Bhagat Singh was once sheltered here for a few days. Eventually, Singh was transferred to Daryaganj in Old Delhi.

The home is now inhabited by Sikander Mirza Changezi, Naseem’s son and also one of the founding members of the Hazrat Shah Waliullah Public Library.

Vignettes like these from Delhi’s colonial past are hardly ever widely available, Abu points out.

“There’s plenty of information on the food and the popular monuments. But what about the unheard stories? I wanted to tell these stories from a first-hand witness,” Abu explains how his idea took off as more people joined the bandwagon.

The team is now focused on replicating the model across other Indian cities, through their ‘Tales of City’, an arm of Purani Dilli Walo Ki Baatein.

With every new walk, there are new worlds to discover.

Food: the poster boy of Delhi’s bazaars

Mnemonics colour the roads of Abu’s home city.

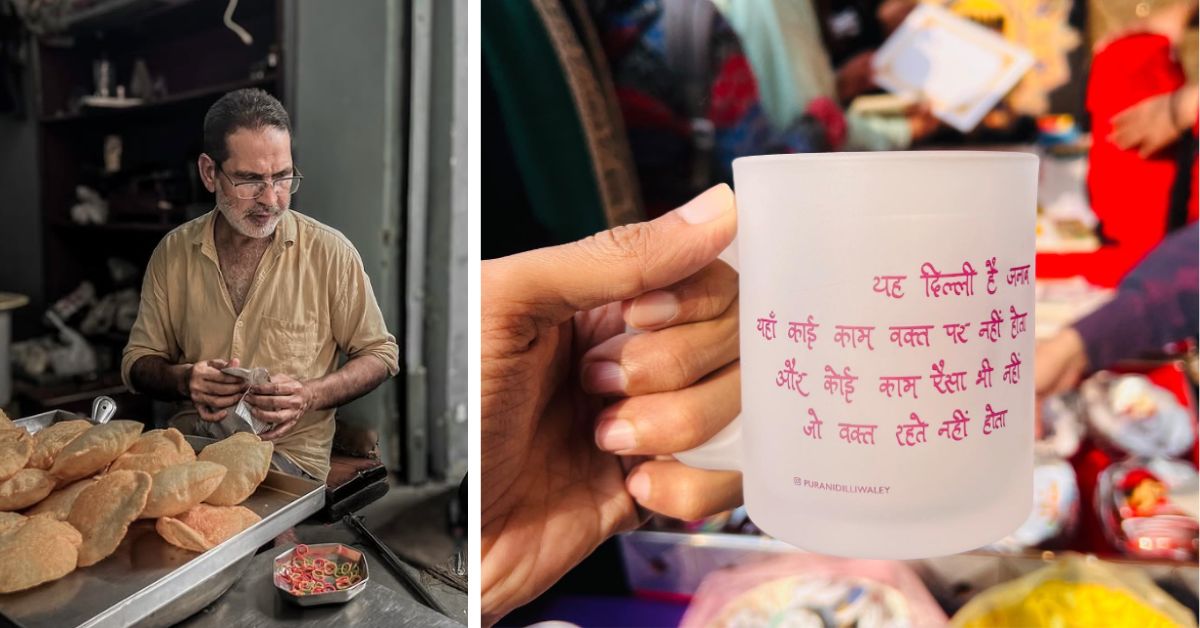

It’s in the bread pakodas (bread slices stuffed with spiced potato filling) that one of the stall owners, Pramod, whips up with clockwork precision; in the sizzle of the jalebis (spiral shaped Indian sweets); in the beauty of the chhatris (cenotaphs); in the rickshaws that can be heard jostling through the traffic, in the Sufi music that thrums through the air in the evenings, in the pungent air at one of Asia’s largest wholesale spice markets Khari Baoli and in the conversations he has with strangers.

These are mnemonics — hacks that help him touch base with core memories of the town he grew up in.

The beauty of Old Delhi, Abu shares, is that people don’t let the future consume their minds. Underscoring this through Pramod’s story, Abu says he sets up his stall at 5 pm. By 6 pm, his batch of bread pakodas is wiped clean.

In Old Delhi, no one is in a hurry to push themselves, or eke out more than they need to, Abu points out. “They set up their stalls knowing how much they’d love to earn for the day, earn that much and then wrap up and go home,” he adds, recommending that, if ever you’re here, you try the tikkis (cutlet) and chutney at Pramod’s stall; these are “zabardast” (amazing).

Delhi’s street food sees a capricious dynamic. Light eats are interspersed with heavy biryanis (aromatic rice cooked with meats); then there are the foods whose arrival on the plates is prequelled by as compelling stories.

For instance, the long chirey. One of Old Delhi’s best vegetarian street snacks, the name is inspired by the slender shape that resembles little birds.

“It’s made from a mix of gram flour and ground lentils; the batter is seasoned with green chillies, onions, and herbs before being shaped around thin skewers and grilled over open coals. The result is a beautifully curved fritter with a smoky crust and a tender, cakey inside. Long chirey was once sold on the steps of Jama Masjid,” Abu shares.

Then there are the dori kebabs, a cheeky nod to Delhi’s smoky eats. “Made from finely minced meat, the kebab is so soft that it must be held together with a thin cotton thread while being grilled. When served, the kebab arrives on a leaf plate, the thread intact. It is served with paper-thin rumali roti (Indian flatbread), sliced onions, and fiery red chutney,” Abu shares.

Vying for counter space is the laal safed phulke (gram flour fritters that are fried until they puff up and then immediately soaked in water or spiced brine); the white phulke absorb salted water, becoming soft and airy, while the red ones soak in a chilli-spiked, tangy liquid that gives them a fermented zing.

These have found favour in Fatma Laiba (20), who has been a loyalist at Abu’s walks. When Fatma moved to Delhi in 2022 to pursue a degree in sociology, she had a fair picture of the Sufi-ism, the dargah (shrine) culture and the most popular spots.

“But, Abu bhai introduced me to some really niche places of Old Delhi, little-known streets and of course the nalli nihari (mutton stew) and dori kebabs,” she says. When Fatma would go on these walks and later talk about everything she had learnt, in her circle of Gen Z friends, they would be compelled to enquire more.

“They were always intrigued by the workshops I was doing, or the new places I was seeing on these walks. They would ask to come along, and they did. They would love everything they learnt; it’s because of the presentation that Abu relies on. The content appeals to anyone interested in history, whether it’s a senior citizen or a youngster,” she adds.

But, while admitting that food is indeed the zeitgeist of the landscape, Fatma says, there is so much more too, that Old Delhi has to offer.

Purani Dilli: where joy is the common denominator

“Growing up in the vibrant lanes of Old Delhi, one of the most captivating experiences was witnessing the juloos,” Abu writes in one of his posts. He’s referring to the parades that colour the streets on the occasion of different festivals.

One of Abu’s most priceless childhood memories is that of witnessing the Ramlila ki sawari. “This iconic procession was initiated by Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar for the Hindus of Shahjahanabad. Despite his exile to Rangoon after the 1857 revolt, the roots of this custom have dug deep, allowing it to thrive for over 180 years,” he writes.

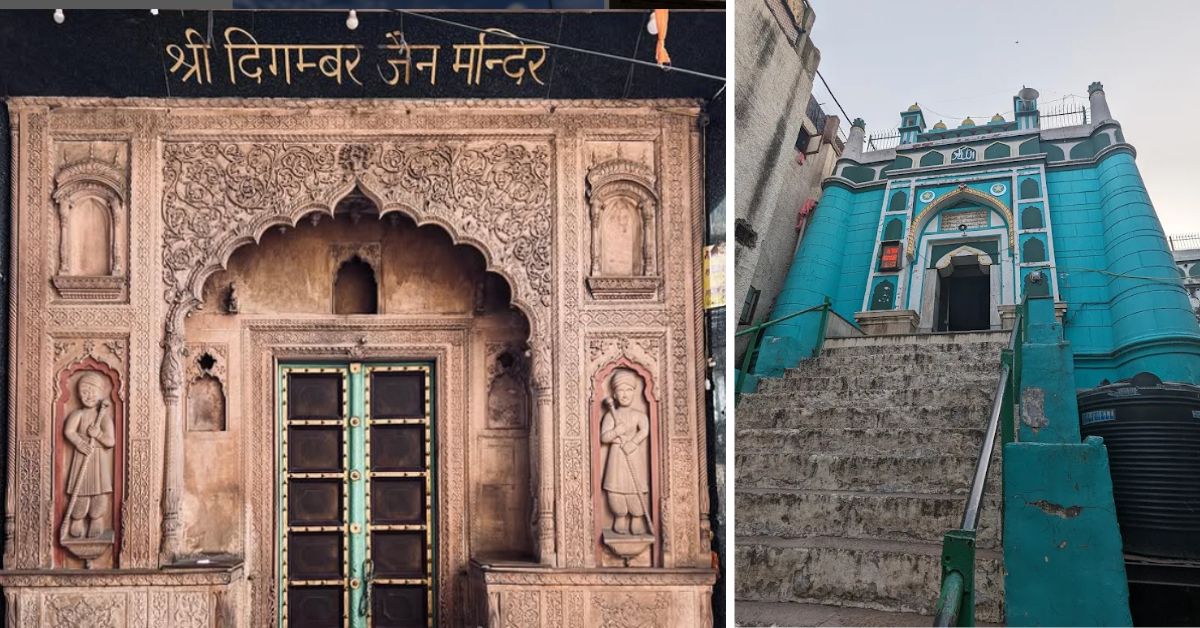

His experiences of juloos converge on a single truth. “This is perhaps the only corner of the world where a temple, gurdwara, mosque, and church share the same wall, living together in harmony, never treading on one another’s sentiments.”

The walks also tap into this part of Old Delhi.

As for the monuments, Abu’s walks cover those too. But you won’t just be witnessing the usual ones; there are ones he’s stumbled on over the years that he now wants you to see.

These include the Kalan Masjid built in 1387 CE, around 269 years before the iconic Jama Masjid; the 200-year-old Jain mandirs (temples) with their Rajasthani carvings and beautiful courtyards, and the structures that have remained a footnote in India’s history.

There is so much to explore.

If Abu had to describe Delhi, he says, one word wouldn’t be enough. “It’s poetry, it’s celebration, it’s mystique, it’s acceptance.” And all he wants is for you to fall in love with this multi-hyphenate city, just like he did.

You can sign up for a walk here.

(@talesofcityofficial)

(@talesofcityofficial)

No comments:

Post a Comment