“This is the problem with you girls…You will study hard, score high marks and then give it all up after marriage.”

Dr Mangala Narlikar’s colleague’s brutally honest words churned a silent storm inside her. Waiting in queue at the London Heathrow airport in the summer of 1972, she glanced at her two toddlers and her husband, Jayant, and wondered what her life was going to be like in India.

She had just turned 29 and was torn between pursuing her innate love for Maths and her family.

After sincerely dedicating six years to taking care of her family, the renowned astrophysicist, Dr Mangala, was about to enter a new phase of her life in Mumbai. This was probably a chance to revive her career in Mathematics.

However, her responsibilities only increased when her in-laws moved in with them once they were back in Mumbai.

Meanwhile, Jayant joined the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR). He was in-charge of the Theoretical Astrophysics Group. Interestingly, Dr Mangala had worked at TIFR as a research associate for a brief period before marriage and the institute happened to be on the same road as their house. This inspired her to join TIFR again.

“Till then, I had never prioritised my career because of my choices but now I took the hard decision of juggling two worlds. Jayant and my in-laws were always supportive so there at least I didn’t have to battle. I knew it would be tough, but I decided to work and do my PhD,” Dr Mangala, who now lives in Pune, tells The Better India.

In 1980, she obtained her PhD in Analytic Number Theory from Mumbai University (MU) while working in the school of Mathematics at TIFR. In her final year, she got pregnant with her third daughter.

She mentions how MU would adjust lectures according to her schedules and even the TIFR showed flexibility. “Even now it seems surreal that so many people fueled my career. No doubt, time management was the biggest challenge for any woman juggling two worlds, but unwavering support from society makes a huge difference and that’s exactly what happened in my case,” she adds.

Till Dr Mangala became a mother of three, she was known as the wife of the scientist who developed the conformal gravity theory, called ‘Hoyle–Narlikar’ with Sir Fred Hoyle. But there were only a few who knew this lady was a Math wizard.

‘My single feisty mother gave me the wings to fly’

Born in 1943 in Pune, Dr Mangala’s family gave utmost importance to education irrespective of one’s gender. Her father worked in a government service job in Mumbai and her mother had completed only one year of college.

Six months after she was born, her father succumbed to cancer and the entire responsibility of looking after Dr Mangala and her brother fell on her 21-year-old mother.

“It was the biggest blow for our family as my mother had no financial support or job. Some advised her to remarry and some told her to take up a teaching job as it was suitable for a ‘woman’. But my strong-willed mother, with nerves of steel, wanted to become a doctor. She convinced my grandmother and moved to Pune to pursue her MBBS. Meanwhile, my brother and I stayed with our grandparents in Mumbai,” she recalls, adding, “In retrospect, this was a highly unusual situation for a widow in the ’40s. She was the only female doctor in our family and was way ahead of her time.”

Dr Mangala grew up watching her mother work hard to build her career. Her mother was her “superwoman” for whom the sky was the limit. She says, “I have desired to be like her every day of my life.”

Needless to say, Dr Mangala imbibed similar qualities and excelled in academics, particularly Maths. She would go on to pursue BA and MA in Maths.

“I knew Math was a male-dominated subject back then, but I couldn’t accept the generalisation that girls are bad at Maths or the calculations jokes because here I was, topping all my examinations, including my final year at the university,” she says.

When asked what attracted her to the subject, she says, “It is logical thinking and universal truth that brings people together. You cannot debate or brand your argument as the superior for there is just one answer to every math problem. If you want to learn universal ethics and norms, Math is a brilliant teacher.”

Moving Countries & Raising A Family

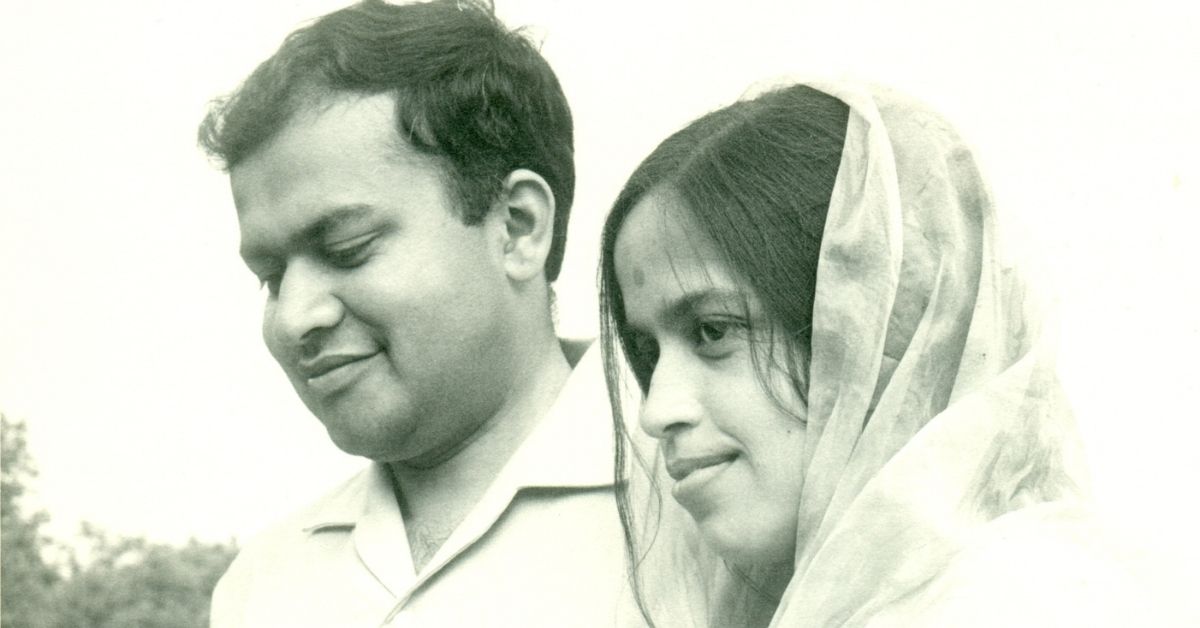

At 22, Dr Mangala was working at the TIFR and a year later in 1966 she was married to Jayant. Although it was an arranged marriage, Dr Mangala gushes about their first meeting.

“I was very awkward but he made me feel comfortable by sharing jokes and funny incidents from his days at Cambridge. I found him extremely thoughtful and supportive of my love for Maths. Unlike other men, he had no issues with my intellect and the desire to study more,” she recalls.

However, Dr Mangala willingly put her career in the backseat when they moved to Cambridge, England, in 1966. She shares how excited she was to learn cooking, blend with other cultures and experience the cold climate.

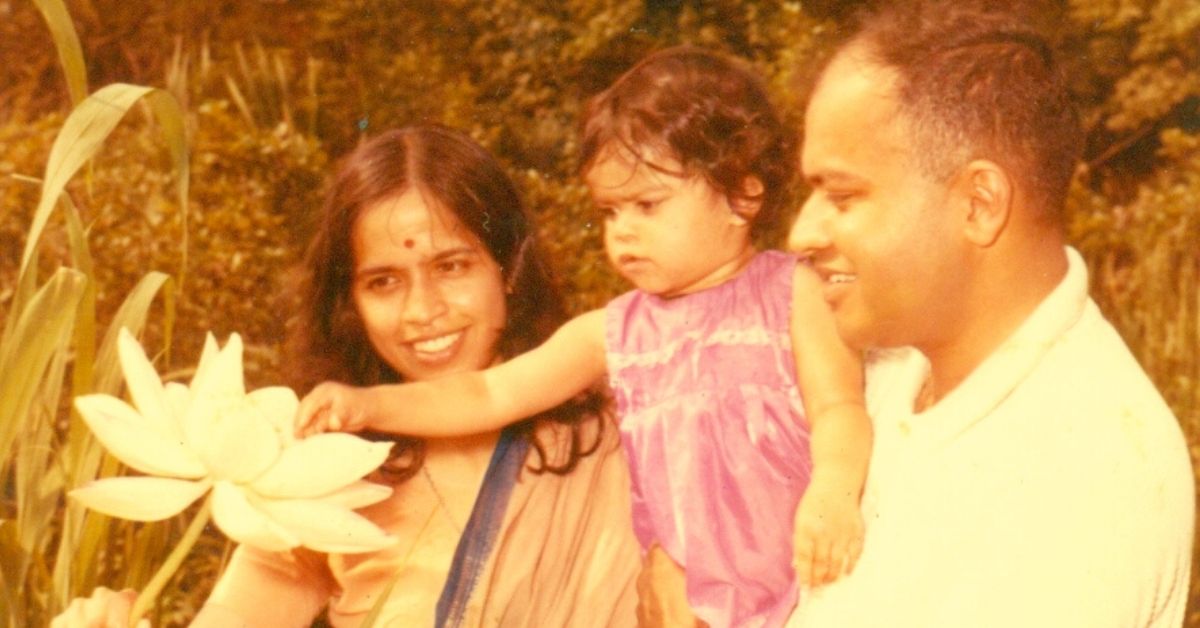

During those six years, Dr Mangala did conduct a few lectures for undergraduate students and even took some tutorials. She gave birth to two daughters in the UK. Her most cherished memories, she says, remain to be the ones where she got to travel to different countries because of Jayant’s work.

Making A ‘Mathematical’ Mark

While doing her PhD, Dr Mangala’s days would begin as early as 4 and she would study till late at night. She juggled classes, getting the children ready for school, cooking, looking after the needs of her in-laws and also teaching part-time at MU. It was an exhausting routine that left very little time for herself. But the whole chaotic experience taught her something — she was capable of a lot.

During that period, she would go on to write several research papers like Theory of Sieved Integers, Acta Arithmetica 38, 157 in 19; Mean Square Value theorem of Hurwitz Zeta Function; Proceedings of Indian Academy of Sciences 90, 195, 1981; Hybrid Mean Value Theorem of L-Functions; Hardy Ramanujan Journal 9, 11-16, 1988; and so on. She also wrote papers that broke down complicated Math language into simpler terms

In 1989, she moved to Pune and joined the Department of Mathematics at the University of Pune as a part-time professor. Later, she also taught M.Sc students at the centre in Bhaskaracharya Pratishthan from 2006 to 2010. By now, she was a known name in the Math community and was often invited as a guest lecturer in Universities.

Dr Mangala does not exactly remember if it was her daughters or a eureka moment that inspired her to work on children struggling with the subject.

She says, “I started teaching children of my domestic help and later even joined an NGO that taught girls living in slums for free. While teaching them, I realised I have the calibre to make them understand Math in a simple yet fun way. That led me to Balbharti, the Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production & Curriculum Research centre with my proposal to make contributions in the school textbooks.”

Dr Mangala not only went on to write books but also made concrete changes to the way textbooks are published. The books that she wrote were strictly published for just Rs 10 so that every child could afford them. As for textbooks, there were more pictures and interactive problems.

In 2013, Dr Mangala was appointed as the Chairman of Balbharti who made several significant developments in the state curriculum. But her biggest contribution was simplifying the names of numbers.

“In Marathi, for example, 32 is called ‘Battis’ wherein the tis (30) comes later. It is confusing for a child. In English, the same number in writing as ‘thirty-two’ so it is easier. Now, schools have the option of either calling it ‘battis’ or ‘teen-don’,” she says.

Although Dr Mangala retired a couple of years ago, she has kept herself active by being a guest lecturer at Pune University. The 77-year-old says she is still hungry for knowledge. During the lockdown, she learnt how to operate a tablet and conduct online classes for the university students.

Looking back, Dr Mangala tells me there were things she could have done differently, given a chance but that she is content by optimally using opportunities she received.

As we come to the end of the interview, the ever-smiling Dr Mangala reiterates that she was not discriminated against because of her gender but has definitely seen the people around her facing this issue even in 2021.

“Any human, irrespective of gender, can grow if we consciously create an environment that promotes intellect over inhibitions, progressive thinking over regressive norms,” she says.

All images are sourced from Dr Mangala.

Edited by Yoshita Rao

No comments:

Post a Comment