Its beauty and difficult terrain make Hangrum [a village in Assam] a dramatic setting on a knife-edged ridge; range after range of the Manipur hills looming blue and green out of the cloud on one side of it, razor-backed spurs sweeping down to the Jenam on the other, the forbidding mass of Hemeolowa blocking the outlook to the south; its smoke-stained houses a study in shades of brown and tan and darker brown, like a sepia drawing.

Arkotong Longkumer attributes this picturesque definition of Assam’s Hangrum village to Ursula Graham Bower in his book — ‘Reform, Identity and Narratives of Belonging: The Heraka Movement in Northeast India.’

It is hard to imagine then that such a quaint village was once utilised for its escape routes to the Manipur border by a female freedom fighter, Rani Gaidinliu, during the Hangrum war of 1932.

While the village’s dangerous terrains made it difficult to communicate, it had a vantage point that overlooks the valley below. It had easy escape routes along its smaller ridges leading to the Manipur border.

While Rani Gaidinliu’s contribution to the freedom struggle eludes most history textbooks, this teenage girl fought among Hangrum men against British rule.

Arkotong narrates his discussions with a Hangrum village elder who said, “A network of tunnels, back entrances and secret hideouts made her inconspicuous to the British but very visible to the people. Their confidence and faith in her strengthened. Rumours of her exploits—turning bullets into water and foiling assailants of her party by her magic (kiantau)—spread like wildfire.”

A goddess among us

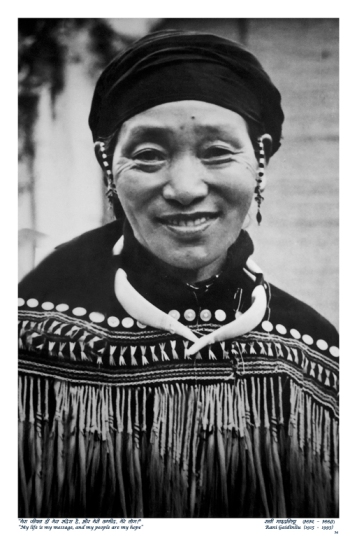

For a tale as telling as Rani Gaidinliu’s, she had rather humble beginnings. Born in a small Manipur village called Nungkao, also known as Luangkao, in the Tamenglong district on 26 January 1915, Gaidinliu was brought up without a formal education. Yet, she was educated in their indigenous way.

The women’s accounts of Gaidinliu, as per Arkotong, speak of her strong features of a man dressed in women’s clothing.

Having learnt about her when he was barely 5-years-old, Richard Kamei, a doctoral candidate at Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, says, “Elderlies regularly narrated to us about her with great reverence as a revolutionary fighter for our Zeliangrong’s land and people. Rani Gaidinliu belonged to the Rongmei Naga tribe, which is also our tribe, one of the cognate tribes under Zeliangrong.”

Steeped in culture, Gaidinliu was always keen on preserving the Zeliangrong people’s heritage, who are still spread across Assam, Manipur and Nagaland.

Growing up in British India, she witnessed her cousin and the clan’s spiritual leader, Haipou Jadonang, speak up against British missionaries who sought to convert the Naga tribe. Both Jadonang, as well as Gaidinliu, were seen as prophets among the tribes. While Jadonang was seen as a ‘promised saviour’ of the Zeliangrong people, Gaidinliu was revered as an incarnation of the Goddess Namginai.

But the burgeoning of Christianity in the Northeast was seen as yet another instrument—among a plethora of adversities—of colonisation of the indigenous people.

“She, along with her predecessor, Jadonang, foresaw that erosion of one of the elements would lead to disruption in the indigenous people’s lifeworld. With external forces in the form of colonial rule unleashing taxation on their lands, administration, free and forced labour, Christian missionaries and cultural imperialism at play, the Zeliangrong movement incorporated cultural, religious, and political aspects to demand freedom and liberate their people and their lands,” says Richard.

So, at the tender age of 13, in 1927, she joined the socio-religious movement initiated by Jadonang called Heraka, which translates to ‘pure’. The teenager’s iconic words are echoed even today when she said, “We are free people; the white man should not rule over us.”

The movement was an attempt to establish self-rule by the Nagas. The people of the land propagated the worship of one of the many gods of the Zeliangrong community called Tingkao Ragwang — the supreme ‘creator’. This was done in an attempt to resist conversion to Christianity by the British Raj.

However, the colonial powers saw Jadonang as ‘inventing’ a religious cult and labelled Gaidinliu as a ‘sorcerer’. In 1931, Jadonang was arrested by the British Raj under charges of sedition and alleged involvement in the murder of Manipuri traders. He was hanged to death on 29 August 1931. It was then up to Gaidinliu to carry the movement forward.

The War of Hangrum

Taking up the mantle, Gaidinliu regularly preached akin to Gandhian principles and instigated her people not to pay taxes and rebel against the Raj. In her words, “Loss of religion is the loss of culture, loss of culture is the loss of identity.”

The Zeliangrong tribe came together to resist colonial rule and several repressive measures imposed by the police and Assam Rifles and refusing to pay fines. This was seen as their own version of the Non-Cooperation Movement in the Northeast.

At the age of 17, Gaidinliu valiantly led many guerilla warfare tactics against the British. Arkotong writes, “On 18 March 1932, about 50 to 60 fighters from the village of Hangrum rushed down a slope and attacked the sepoys who were positioned below in their post. The vantage point of the soldiers below could not have been better. Those rushing down the slope were easy targets for those with guns; spears and arrows were no match.”

Soon after, she used the escape routes leading to the Manipur border and went underground.

According to Arkotong, Gaidinliu instructed the people of Pulomi village to build a huge fortress that would accommodate her and her warriors. He writes, “It was a palisade copied from the Hangrum fort, according to those who witnessed the construction. Gaidinliu herself was blockaded inside with her followers. The stockades built were 18-feet-high.”

However, on 17 October 1932, Gaidinliu was captured by Captain Macdonald, who made a sudden attack on the village. She was taken to Kohima on foot and later to Imphal, where she was tried under charges of murder and abatement of murder. Later, she was sentenced to life imprisonment under the Political Agent’s Court.

The ‘Queen’ of the Northeast

In 1937, on his tour to Manipur, Jawaharlal Nehru met Gaidinliu at the Shillong Jail and promised to free her. Gaidinliu was described as “The daughter of the Hills” in an article by the Hindustan Times, where Nehru conferred her with the title of ‘Rani’.

He is also said to have written to the British MP, Lady Astor, for the release of Rani Gaidinliu but to no avail as they stated that if Rani was released, “she may be troublesome for the Raj, again”.

After 14 years in prison, Rani Gaidinliu was finally released in 1947, after India’s independence. After which, she continued to work for the betterment of her people. She demanded a separate Zeliangrong area within the Union of India.

She was forced to go underground once again in the ’60s as she faced opposition from other Naga leaders.

Richard says, “After the ’60s, she led a movement demanding a homeland for Zeliangrong people inhabiting the states of Assam, Manipur, and Nagaland. She also made regular interfaces with the Centre, especially the then Prime Ministers, Indira Gandhi, and Rajiv Gandhi.”

For all her efforts in the freedom struggle, she was awarded the Tamra Patra in 1972, the Padma Bhushan in 1982, the Vivekananda Seva Award (1983), and the Birsa Munda Award posthumously by the Government of India.

The Government also issued a postage stamp in her honour in 1996 and a commemorative coin in 2015. But the completion of the multi-crore project of Rani Gaidinliu Women’s market at Tamenglong, which was inaugurated in 2018, still awaits its grand opening.

Government of India released a coin in memory of the nation’s Freedom fighter late Smt. Rani Gaidinliu pic.twitter.com/GQKopuUvZN

— miZO zEITGEIST (@mizozeitgeist) February 18, 2020

Rani Gaidinliu passed away at the age of 78 on 17 February 1993, but her legacy still lives on among her people who hold her in deep regard even today.

“Her struggle is a message to India, and beyond that, the rights and interests of indigenous communities must be acknowledged and fulfilled,” Richard signs off.

(Edited by Vinayak Hegde)

No comments:

Post a Comment