“When we were little and the police would raid our houses in the middle of the night, we’d see people jumping over walls and running away. My grandmother would wake up all the children in the house, gather us together, and tell us to read out loud, so the police would know that school-going, regular children lived there. I always found this so strange. Why were we constantly told to hide, to run? What crime had we committed that made us feel that our existence was dishonest?” shares Naseema Khatoon.

Naseema, 39, was born and raised in a red-light area, experiencing firsthand the stigma and neglect faced by sex workers and their children. Today, having broken free from the cycle of poverty, she has become a powerful voice for the marginalised.

“It’s when I was enrolled in school that I developed a sense of inquisitiveness about my identity. I would be, for the first time, in an environment where people would ask me my full name and where I was from. But I was told not to tell people where I lived,” Naseema tells The Better India.

Life in a red-light district

Naseema’s home was Chaturbhuj Sthan, a red-light district in Muzaffarpur, Bihar. Named after a Vishnu temple, the area has historically been home to sex workers and tawaifs; its religious name does not shield the community from societal stigma.

“Why should I not tell people who I am and where I come from?” Naseema remembers asking her father, who quickly shut her down.

“The girls from school would all walk home together, but they would take a long wounded route to avoid my gully. They were told to, so I’d go alone,” she says.

As a child, Naseema was a witness to frequent police raids in her neighbourhood. These experiences left a lasting impact, and it was during this time that she began to fully understand the marginalisation her community faced.

The constant fear of the police, the forced hiding, and the need to constantly run were not just external pressures; they profoundly shaped her self-perception and her struggle to define her identity.

“It is hard to define yourself as a daughter of a red-light area and not a sex worker. This is a concept that is unheard of to the outside world,” she says. But Naseema never let go of her desire to define herself beyond what the world forced on her.

“Just as someone who has a small vegetable stall that he pushes around on the road, wouldn’t want their child to continue doing the same work they do, a sex worker also does not want their child to continue to do the same. She wants better for her kids,” Naseema reflects.

‘I was always so scared’

In 1995, when Naseema was a young teen, IAS Rajbala Verma, who was posted as a district magistrate, started some programmes to help sex workers in the area learn skills, such as embroidery, and get access to healthcare. Naseema took part in one such programme — ‘Better Life Option’. She had already learnt embroidery from her mother, was skilled at it, and stood out. But even then, she struggled with the anxiety of having to answer certain questions.

“I was always so scared that I wouldn’t even speak. Because what if that conversation leads to them asking me where I’m from?” she admits.

At just 13 years old, she was forced to leave school and move to Sitamarhi to live with her maternal grandmother. However, by this time, she had already resolved to build a life for herself, one that would need no hiding.

“I had heard about an organisation there that was helping adolescent girls. I did not know what they did or how they could help. I was sure that if I just tried a little, I could figure my life out and make something of myself. So, I locked myself in a room for days, refused to eat or speak to anybody, until I was taken to where that organisation was,” she says.

“My father kept asking why I wanted to go there, and I would say that there is a friend that I really want to meet,” she chuckles. Her persistence paid off, and one day she met with the people from ‘Adithi’, an organisation that works for underprivileged women.

The very next day, Adithi workers came to her house and urged her father to let her become a part of the organisation where she would learn valuable skills and turn her life around. “I was so stunned when they came to our house. It was like my legs had become jelly and the cola that I was supposed to serve them, wound up on their clothes. I laugh as I say that now, but that day I could have died of relief,” she says.

She worked with the organisation till 2002, becoming a skilled micro-level planner and trainer. Her years in Sitamarhi with Adithi taught her about the law, child rights, and the safety the Constitution grants each and every citizen of this country.

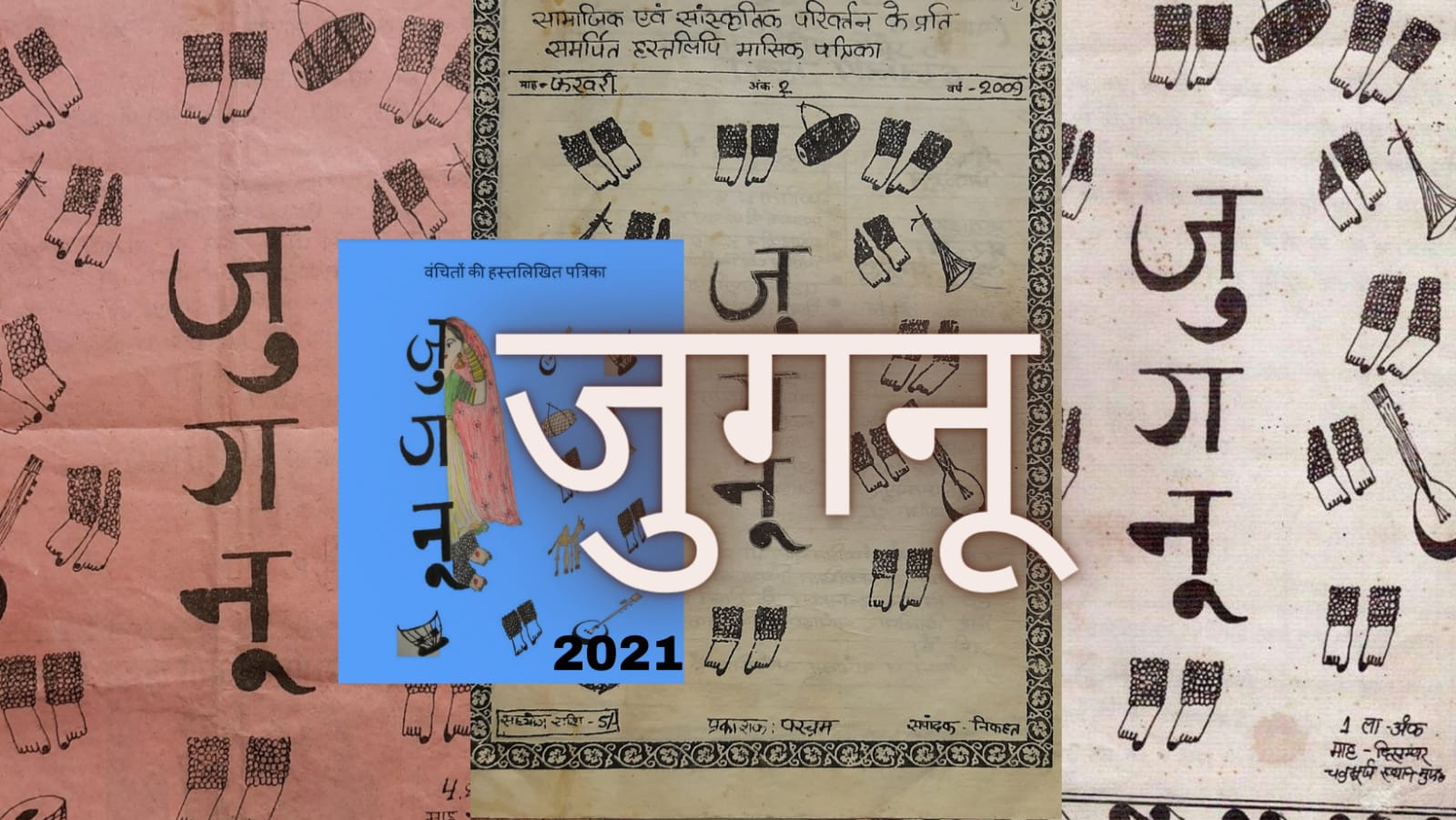

‘Jugnu’: Where children express their dreams

When Naseema came back to Muzaffarpur in 2002, she saw the issues plaguing her home town with a renewed sense of understanding.

“There was a raid in the area right next to us, women were arrested and taken away without the presence of a female constable because those rules, for some reason, do not apply here,” she says.

“The next day, I sat at my father’s tea stall, watching as the police rounded up people from the area. A meeting was taking place, led by the ‘Samaj Sudhar Committee’, where they told the women they could learn skills like tailoring, embroidery, and other jobs offered by government schemes. When the women asked when they could start working and how soon they would get the money, they were told it would take six months to set up,” she shares.

“When asked how they could earn a living in the meantime, the committee took it as an insult. As if we are not allowed to ask questions that dictate whether we get to eat two meals a day or not,” she adds.

Naseema was aware of the challenges faced by the children in the community. When the woman, often the primary breadwinner, is arrested, who takes care of the family? The dependents, especially the children, are left to suffer. “And if there’s a young girl in the household, what options does she have?” she asks.

Naseema’s work with Adithi, along with her increasing involvement in community issues, led her to start a community-based organisation called ‘Parcham’, meaning ‘flag’ in Hindi. Parcham was not an NGO; it was a grassroots organisation built by the people of the community, for the people of the community.

“I looked around and saw what the situation was in terms of education, child rights, employment, and was trying to look at alternatives, of which there were none,” she shares.

“Even when I interacted with the media to speak about these issues, they would somehow not mention that these are the children of sex workers, not sex workers themselves, just to sensationalise the reports,” she shares.

While working with Adithi, Naseema had helped start a magazine named Injoriya, meaning ‘a night full of light’, inspired by the adult education ‘prod’ programmes run by the Government in the 1970s. These programmes helped older women learn to read and write, and the material they created was collected and turned into a magazine.

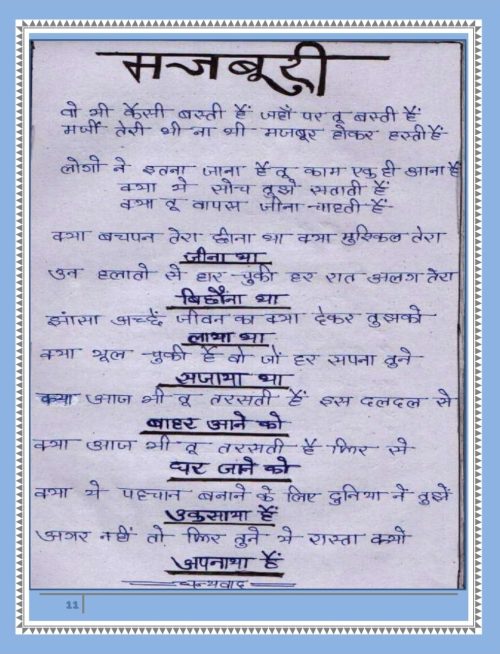

“I thought, why not bring the same idea to my community? A magazine made by the people of the community, telling our own stories,” she says.

“We decided that if no one else would write the truth about us, we would. Even though many in our community couldn’t read or write, we thought it didn’t matter if our writing wasn’t perfect — we would still write and share our voices,” she adds.

In 2004, she started Jugnu (meaning ‘firefly’), a publication designed to amplify the voices of the marginalised. The first edition, a modest four-page photocopied issue, was printed with the help of local funds. Today, it is a 36-page-long magazine, with 10 active reporters from Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Mumbai and Bihar.

“We have a rule here in Jugnu, everybody who is associated with us carries around a copy with them. If somebody asks them who they are, and where they come from, they can just say that they are a Jugnu reporter,” Naseema proudly shares.

Jugnu soon became more than just a magazine; it became a platform for children to express their dreams, hopes, and struggles. One of the key columns in the first edition was, “What is our dream?”; a question rarely asked of children from such communities. “We asked that question, and the kids would come and write what they wanted to become,” she shares.

Becoming a voice for marginalised communities

M D Arif, a 24-year-old who used to draw and paint for Jugnu when he was seven, wrote that he wanted to become a police officer. “In the first few editions, I would often draw. Once, I wrote for the ‘What is our dream’ column. But now, I write about more complex things that we see around here in Muzaffarpur,” he shares, adding, “That includes child labour and identity politics.”

One especially poignant piece he worked on covers the lives of sex workers who have given up their profession due to old age. “I spoke to people and found that even though it has been years since they have retired, they still call themselves sex workers. It is so deeply ingrained in a person’s identity and there’s really nothing wrong in that either,” he says.

An active member of Parcham and now a member of his college’s NSS team, he often conducts meetings, telling people about their rights and teaching them how to ask for them. “Jugnu gave a lot of us the freedom to speak about ourselves, who we are, and where we come from; without hesitation, without fear,” he smiles.

As much as Naseema wanted to continue her work, by 2012, the magazine had gone dormant as she moved to Rajasthan and started a family. But the dream never died. In 2021, she revived Jugnu with a renewed focus on expanding the magazine’s reach beyond Muzaffarpur. Now Jugnu was not just a magazine of the red-light district — it represented marginalised communities across Mumbai, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and Rajasthan.

“Not a lot of people know me in Rajasthan, but people do know Prem,” says Naseema, looking back at the remarkable journey of Premnath, a 20-year-old from the Kalbeliya community in Barmer, Rajasthan.

Prem met Naseema in 2018 at an event and soon became involved with Jugnu, writing about the nomadic tribes of Rajasthan. Growing up, as he saw his parents having to beg to bring food to the table, he knew that he would not be able to continue his education much longer.

“Our people were nomads. We never settled and as a result of that, we don’t have any land to call our own. Without an address and IDs, we cannot get proper documentation. If someone from our community passes on, there are chances that we might have to try a few villages to check if somebody would house our dead,” he says. And these are the things he writes about in Jugnu, today.

“I have managed to get a college education because of Jugnu,” he shares. A final-year political science major, he has become an active writer and reporter, shedding light on the issues his people face.

Empowering children through ‘Police Paathshaala’

Naseema fondly recalls the time she encouraged Prem to visit the collector’s office and present him with a copy of the magazine. Though hesitant at first, Prem took the initiative and impressed the collector with his determination. When Prem mentioned the challenges of studying at the Gaushala (cow-shed) due to lack of electricity at home, the collector immediately took steps to rectify the situation.

“This is where we realised how this magazine can help us,” says Naseema. “It’s not just about me. It’s about any marginalised community that feels unheard.” Reporters treat the magazine as their own constitution, and Naseema encourages them to share it with others. “If people pay you the support funds, great. If not, it’s never a waste. It will at least make them realise that you are a reporter or writer, someone powerful.”

In November 2023, Naseema also started a pioneering initiative, called Police Paathshaala, in her hometown. The programme aims to change the way children of Chaturbhuj Sthan engage with the police. Officers teach the children, play with them, and even bring them cakes.

Naseema reflects on the stark contrast between her childhood and what these children experience today. “When I was little, I was always told to hide from the police, to fear them. But these kids? You should see them jump around and boss the officers, it’s quite funny!”

The programme began in a spare police room that was going to waste and has since grown from 15 children to over 100. Many of these children, like Naseema once was, are school dropouts who face societal stigma. Yet, they proudly identify themselves as “the kids of Police Paathshaala”. Arif, with his dreams of being a police officer still intact, closely works with these officers.

Despite regulatory hurdles, the goal remains to make the magazine profitable, so the children involved can benefit from the funds raised. For now, reporters receive copies of the magazine and keep whatever support funds they can collect from distributing them. Financial support from donors, such as the MG Charitable Trust in the US, has been crucial in printing the magazine, with the first 100 copies printed in 2021 thanks to their support.

“If you want to see change, work for these kids — they are the future,” Naseema says. “When Prem becomes somebody, and he will, he’ll carry this goodness forward.”

Edited by Arunava Banerjee; Images courtesy Naseema Khatoon

No comments:

Post a Comment